You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Colin Woodard in Tufts Magazine

There’s been a map circulating online that describes the 11 nations that make up America. Journalist Colin Woodard describes the 11 nations in the fall 2013 Tufts alumni magazine:

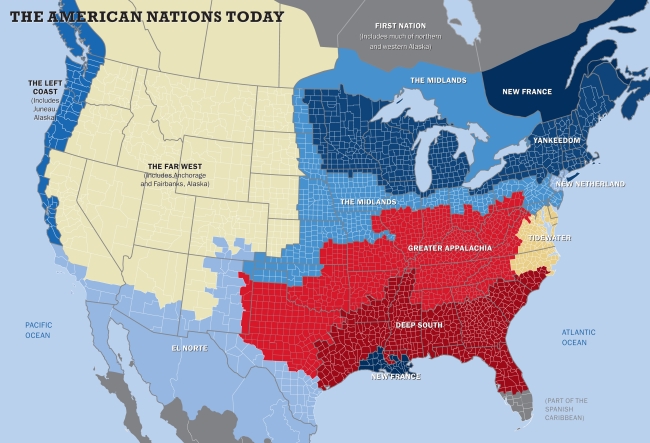

The original North American colonies were settled by people from distinct regions of the British Isles — and from France, the Netherlands, and Spain — each with its own religious, political, and ethnographic traits.... Throughout the colonial period and the Early Republic, they saw themselves as competitors — for land, capital, and other settlers—and even as enemies, taking opposing sides in the American Revolution, the War of 1812, and the Civil War.... There’s never been an America, but rather several Americas — each a distinct nation. There are 11 nations today.

This statement, and Woodard’s research, resonates with my experience living in four of those nations, particularly with my experience growing up in Tidewater, which contains the coastal parts of southern Virginia and northern North Carolina. Until I saw this map illustrated by Brian Stauffer, I always referred to Tidewater (as it’s been called locally for generations) as part of the South. And I unabashedly loved this place that I experienced as friendly and hospitable — with its “all y’alls” and “ma’ams” and “how’re your doing?” by strangers — despite its racist historical culture. Naive, but the truth at the time. Now, I often find myself trying to convince friends, colleagues, and graduate students who have never been to the South that it shouldn’t be written off whole hog when they are considering applying for jobs (or vacationing).

In Woodard’s re-mapping of the U.S., however, I have found a good response to these naysayers, in the sentence that immediately follows the above quote and that brings all the ugly parts of America’s 11 nations into high relief: “Each [nation] looks at violence, as well as everything else, in its own way.”

This column isn’t about the ways that violence is highlighted or hidden in each of the 11 U.S. nations — for that, go read Woodard’s essay — but, instead, is an acknowledgment that every nation has its ugliness, so I am asking you to reconsider limiting your job search if it includes or excludes specific geographic regions. Some job-seekers don’t have the luxury of writing off any region, but my point here is that none of you should be doing so.

This is the same issue when applying to colleges or universities. I’d never even heard of the university where I earned my Ph.D. until my mentor recommended I apply a few months before the deadline. I did apply against my better geographical judgment, considering I was worried I would die in a snow storm when the institution boasted 300 inches of snow a year in its brochures. As it turned out, this Virginia girl likes snow and all of the social norms that a culture filled with snow uses to acclimate. Perhaps, this is the thing to remember when considering a job search outside of your geographic comfort zone: Just as you adapted to grad school and learned a new set of academic customs and disciplinary cultures, you can learn to adapt to your new geographic and cultural climates in your first (or second or third) job. And it could be fun. An adventure, even!

I acclimate easily, as it turns out, and I admit being a pragmatist who doesn’t believe in crying over spilled milk when I can bootstrap myself into a new place when the old one goes sour. It’s important to acknowledge all of the unspoken assumptions that lie in those metaphors, but it’s equally important to Get A Job! Or, sometimes, Get A New Job!, which is why I’ll never understand it when academics tell me they won’t move to Insert State/Region They’ve Never Been To.

If people tell me they “will never live in the South,” what they really mean is something like “I am unhappy with the racial politics of Florida’s Stand Your Ground laws” or “I can’t believe the governor of North Carolina wants to make the educational system even worse” or “I’m gay, and I wouldn’t have any rights in Texas.” All of these points are true, sadly. But if you exclude, say, “the South” from your job search, according to Woodard’s map you would be excluding Tidewater, the Deep South, Greater Appalachia, the Spanish Caribbean, part of New France and the Midlands, and occasionally El Norte. That’s a hell of a lot of the country — 7 of the 11 American nations — that you’re ignoring.

I'm not trying to say that there aren't principled or practical reasons for some academics to prefer or avoid some localities. But given how imperfect our entire nation is, I strongly suggest avoiding ruling out broad sections of the country, such as the South, or such as rural areas or areas associated with particular religious groups or political inclinations.

If you do, what does that leave you with? The rest of this conversation usually goes like this:

So if you won’t apply to jobs in the South, that leaves you with Yankeedom. “But I hate snow; so it has to be warm. But not too warm,” you say.

Then, what about the part of the Midlands that isn’t considered the colloquial South? “Ugh, all that corn! Who’d ever want to live in the flyover states?! There’s nothing to do!” Sigh. Have you ever been to Chicago? Or Minneapolis? Those are great cities and the small college towns in other parts of those states are incredibly affordable.

“No small towns! I’m a foodie!” I guess you didn’t know that the Midlands are a rich source of organic farming and farm-to-fork dining. Too bad for you.

So, then what about the Far West? “Unless it's Boulder or Fort Collins, forget it.” Because you pride hippie beer and pot culture over teaching in a great academic program? O.K. Just saying that as cool as a place like Boulder is, I’ve never met an academic there who likes his or her job. Oh, they LOVE the town, and I get that. But to not equally love your place of employment? Why stay?! It doesn’t matter if you have spousal or family or health connections to a place that make you feel like you have to stay in a miserable position. There is always a way out, a better way. (And that’s advice for another column.)

Finally, you’re left with the Left Coast, but since everyone wants to work in Portland, you’d better branch out.

Utah wasn’t even on my radar when I first started thinking about the job market. But I applied, and the search committee members wowed me with their collegiality, and the on-campus visit proved to be beautiful, fun, and intellectually engaging. So I accepted the offer over another one that wasn’t so collegial in a Midlands town I would have loved to live in. And it proved to be the best first job ever, allowing me to grow as an academic and prepare myself for what might come next. I learned that people were more important to me than place, and it is the people — the department chair, your colleagues, your human resources — that can make or break your career.

Even when I was making a crappy salary those first years and was sometimes stymied by a local culture I was unfamiliar with, my colleagues became friends I took advice from, began collaborating with, and hung out with on the weekends.

It takes at least a year to adjust to a new academic job, a new culture, and a new geography, especially if your new job is in one of the nations you haven’t yet lived in. If you’re not totally happy with the job two years in, and you’ve maintained your marketability (which I’ll talk about more in another column), try, try again. Apply everywhere you can and that’s a good fit with the job ad, and let the preliminary interviews and the people weed themselves out of your own fit list before you make any rash decisions on where you might live or not.

The key to thinking geographically about a job search is to remember that it’s only your first job, not your job for life. You might have several dream jobs as your career progresses and your academic identities and goals change. The place really isn’t that important; your goals and the university’s fit are. For my first job, I needed people because people were what had been important to me during my Ph.D. work. For my second job, I needed a Ph.D. program in my field to teach in. I found that and an undergraduate program that I fell in love with.

For my third job, I needed the kind of resources a research institution had to help me with my expanding research projects, and people to help make it happen. I found both in a place I never would have expected to live: West Virginia, a state that no one in the U.S. seems to remember exists, except as the butt of jokes. Like I said before, every state has its ugly side. And you can choose to dwell on that, or you can choose to make change and focus on the good things a place has to offer. I know not everyone has that ambassadorial mix of pragmatism and passion, but when it comes to whether you have a job or not, isn’t the more sane approach to be open to the possibilities?