You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/Siberian Photographer

Those of us who are interested in pedagogy typically advocate engaged, active, student-led forms of learning. But in the modern academy, most of us have had to teach at least one large lecture course. Sure, you can be creative and engaged in the small discussion sessions. But what about when you are on that stage, with a headset and a clicker, PowerPoint slides looming behind you and 200 students are waiting eagerly for the week’s TED-like talk (if they are lucky to have an eloquent prof) or glaring stone-faced at the stage or their cellphone screens?

Don't despair! Even in the most constrained institutional situation -- and even when, as a beginning professor, you might feel the most powerless -- there are easy yet constructive ways to make a difference in a standard lecture format and to make learning your objective. Some of those ways might focus less on the actual lecturing you do and more on how you introduce and frame the course.

To that end, I’d like to share some tips I recently picked up about how to turn a traditional introductory lecture course into a student-centered learning experience. They come from Anne Balsamo, a co-founder of HASTAC (Humanities, Arts, Science and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory) and the inaugural dean of the new School of Arts, Technology and Emerging Communication, or ATEC, at the University of Texas at Dallas -- one of the most visionary programs in technology and society in the country.

Every year, Balsamo offers ATEC's entry-level lecture course, Introduction to TechnoCulture. (You can find a 2017 PDF online of the course, in an earlier evolving phase.) As the name suggests, the course introduces students to “the ways in which technology and culture are intertwined” and invites them “to consider how technologies shape culture and how culture transforms technology.”

Here are three recommendations from Balsamo’s course that you can adapt to any lecture course in any field, as well as to discussion and seminar classes.

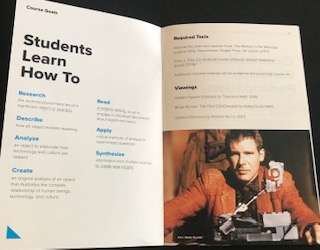

No. 1. Redesign your syllabus as an invitation to learning. Balsamo repackages the bureaucratic, document-heavy, legalistic and impersonal form of a syllabus as an appealing booklet. A typical syllabus these days is enormous -- and deadly. Online or printed out, traditional college syllabi look about as enticing as a terms-of-service agreement -- designed to dull the senses, alienate the soul and disengage the intellect. In short, they are designed not to be read.

And they are unavoidable, especially in a big lecture class. To include all the policies that our colleges and universities now require in this risk-management era, all our reading assignments and options, all our grading and conduct policies, and all our important universities services (for grievances, academic integrity, accessibility, field trips and even campus carry) means creating a very long and dull document.

Balsamo has designed a simple but entirely attractive, readable, enticing printed booklet for her course. It’s not extravagantly expensive nor difficult to design. It can be reused later. Each topic has a clear heading and sometimes an illustration. It’s easy to read and delightful. And it says, "I'm excited about the next weeks we're spending this semester together, and I hope you will be, too." Isn’t that half the battle when meeting 200 -- or 500 or 600 -- students for 75 minutes, week after week after week?

No. 2. Get meta. Let students in on why you think it is important for them to learn what you’re teaching and how it will be useful to them.

We tend to be very poor at explaining the why in higher education. Because we went to graduate school for seven years to get a Ph.D., we are well indoctrinated into why our field is important. Peer review amplifies our professional self-regard. Yet most students think they are taking a given course or learning about a specific text or tool or method just because “my prof told me to.” And, in education, as in parenting, we know how ineffective “I told you so” is for transformation.

Throughout Balsamo’s TechnoCulture booklet, she pauses to tell students not only what she’s teaching but also why. She makes it clear that her students will learn how to “research, describe, analyze, create, read, apply, synthesize.” And each term comes with an explanation and even suggestions about how these skills will help the student beyond this class -- in their other course work, in future jobs, for the rest of their life.

Throughout Balsamo’s TechnoCulture booklet, she pauses to tell students not only what she’s teaching but also why. She makes it clear that her students will learn how to “research, describe, analyze, create, read, apply, synthesize.” And each term comes with an explanation and even suggestions about how these skills will help the student beyond this class -- in their other course work, in future jobs, for the rest of their life.

This is student-centered learning in a nutshell. It includes students in the process of understanding how the formal education in college applies to everything outside and beyond the particular class.

No. 3. Move from punishment to understanding. Of course it is important to state clearly relevant university and class policies about attendance, plagiarism and so forth. But it’s also important to explain to students the ways they can succeed and avoid the problem, not just the punishments for any failures.

Balsamo, for example, has placed the university policy on academic honesty on one page of the syllabus booklet and then, on the facing page, has a section called “How to Protect Your Intellectual Credibility." That information includes three basic tips on 1) making notes of where you find things, 2) learning to love citations and 3) reading Wikipedia critically. Some famous professional historians have gotten in trouble for not being careful about No. 1, for example. International students have different norms for quotation and citation. We can all learn from these recommendations.

Again, this is student-centering learning. The emphasis is not on punishment but on the best way to achieve intellectual credibility. This is yet another skill that lasts not only until the final exam but for a lifetime. Best of all, these are simple changes that any instructor can make in a lecture class, in any field, and we can make them tomorrow. They are simple improvements that make a difference.