You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The fact that Nikole Hannah-Jones’s offer of the Knight Chair at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s School of Journalism was revised to include tenure only after her original offer from the university excluded tenure has shed light on a crucial issue: the underrepresentation of Black women among tenured faculty in the United States. A searchable table of data from the U.S. Department of Education now allows easy access to institution-level information about the number of tenured Black women at 1,458 American colleges and universities in 2019 -- providing many faculty and graduate students clear evidence of just how dire the numbers are at their particular college or university. But the lack of Black women in tenured faculty positions reflects a much wider systemic failure than that of individual institutions.

The problem of underrepresentation is often declared an issue with the “pipeline” that carries Ph.D.s on to tenure-track positions. And there is certainly a “leak” in that pipeline for Black women. In 2019, 1,832 Black women received Ph.Ds. Of those, 522 had an academic job placement. Just 2.7 percent of all academic job placements in 2019 were of Black women with Ph.D.s.

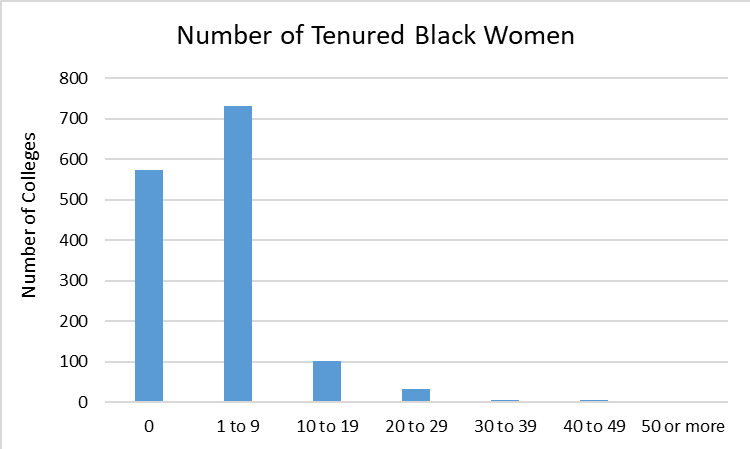

For Black women, underrepresentation continues and increases posttenure. Of all the colleges and universities in the data table, as many as 573 (39 percent) had no tenured Black women faculty. And very few other higher ed institutions were doing much better. Another 732 colleges and universities (50 percent) only had one to nine tenured Black women on campus. Only 10 percent (153 colleges and universities) had 10 or more tenured Black women.

For Black women, underrepresentation continues and increases posttenure. Of all the colleges and universities in the data table, as many as 573 (39 percent) had no tenured Black women faculty. And very few other higher ed institutions were doing much better. Another 732 colleges and universities (50 percent) only had one to nine tenured Black women on campus. Only 10 percent (153 colleges and universities) had 10 or more tenured Black women.

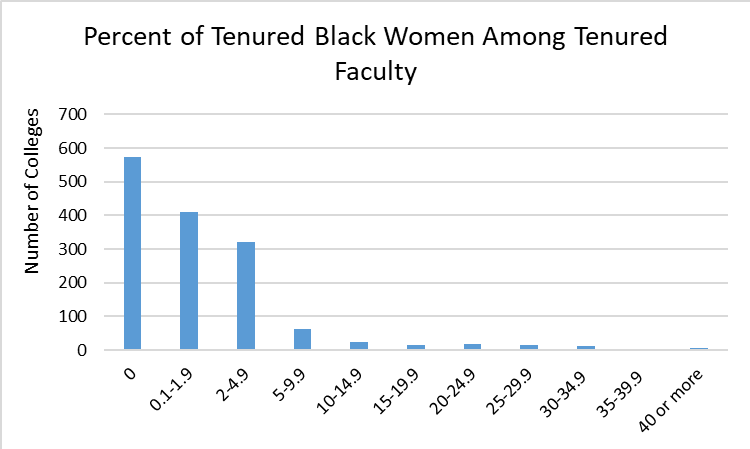

These numbers represent a minuscule percentage, given that about half of the institutions had 70 or more tenured faculty members. At 89 percent of the colleges and universities (1,303 institutions), Black women made up less than 5 percent of tenured faculty. This includes the 573 institutions with no tenured Black women, 409 with up to 1.9 percent and 321 with 2 to 4.9 percent. In total, tenured Black women made up 2.8 percent of the tenured faculty in the U.S. universities in the data set.

While that figure represents the percentage in 2019, it has been stagnant for a long time. According to a TIAA institute report, tenured Black women were 1.6 percent of tenured faculty in 1993, 1.9 percent in 2003 and 2.2 percent in 2013.

The persistent underrepresentation of Black women in higher education goes beyond tenured positions. Black women were 3.7 percent of tenure-track faculty, 3.9 percent of full-time non-tenure-track faculty and 5.1 percent of part-time faculty in 2013. Thus, the greatest representation of Black women in higher education has been in the most precarious academic positions, working in jobs without job security and stability.

The persistent underrepresentation of Black women in higher education goes beyond tenured positions. Black women were 3.7 percent of tenure-track faculty, 3.9 percent of full-time non-tenure-track faculty and 5.1 percent of part-time faculty in 2013. Thus, the greatest representation of Black women in higher education has been in the most precarious academic positions, working in jobs without job security and stability.

The Barriers to Tenure

Often the solution presented to address pipeline issues is to increase the numbers. The logic is that in order to gain more underrepresented faculty members, we need more underrepresented undergraduate students funneled into Ph.D. programs so as to expand the number of Ph.D.s and, ultimately, the pool from which to hire into tenure-track positions. However, increasing the number of Black women with Ph.D.s does nothing to address the structural and institutional barriers that Black women face throughout the process, including microaggressions from faculty and students, invalidation of their research, and the devaluation of their service contributions in the tenure process.

Even when Black women make it to a tenure-track position, racialized and gendered biases influence who gets tenure. We have very little publicly available information about race, gender and tenure due to confidentiality around the process, so we have much less hard data about problematic trends across American colleges and universities. But one report found that the University of Southern California awarded 92 percent of white men tenure between 1998 and 2012 across all social sciences and humanities departments, compared to 55 percent of women and faculty of color. There are likely similar disparities in STEM fields, which have even lower rates of representation among women and faculty of color.

Despite the lack of information available to untangle these patterns by race and gender, we know that Black women face resistance to their presence in the academy from colleagues and students alike in numerous ways. Black faculty face invalidating comments about their research, particularly if it focuses on (or is assumed to focus on) Black people. The phrase “me-search” is often used to discount their scholarly contributions. The far too frequent perception is that the research by Black people of Black people is “subjective” and “biased” and does not contribute more generally to the academic literature.

Both during graduate school and beyond, colleagues may question how Black women gained entry to their departments. Here racialized and gendered stereotypes around excellence and worthiness contribute to assumptions that affirmative action or “diversity hires” brought Black women to the table. These assumptions discount Black women’s merit as scholars and instructors and assume their only value is as an underrepresented minority.

Students contribute to the hostility in academe as they question Black women’s authority in the classroom. Studies of student evaluations show that many students rate their Black women professors as being “less effective” teachers than their peers. These evaluations reflect racialized and gendered assumptions about who is an “expert.”

What’s more, institutional expectations and requirements of those hoping to gain tenure devalue work that is common among underrepresented groups like Black women. The growing numbers of Black college students, including more Black women than Black men, have heightened the demands on the small number of Black women faculty. Both junior Black women and tenured Black women faculty members are at risk of higher rates of taxation for service work. Through this unrewarded invisible labor, Black women serve on diversity committees, mentor marginalized students and provide labor to create inclusive spaces in higher education. Not only do these demands detract from the time they can spend on what often counts most in the tenure process (research), but colleges and universities rarely acknowledge the work of mentoring and diversity service in the tenure process.

The current state of affairs in which only 5,221 Black women across U.S. colleges and universities today are tenured represents a failure to recruit, retain and support Black women in academe. It represents a devaluation of the work we do to mentor marginalized undergraduate and graduate students, provide safe spaces, and promote and advance issues of diversity and inclusion. It represents racialized and gendered assumptions about our expertise and contributions to our fields in both research and teaching. It represents a failure of the system of higher education to acknowledge that the demands of work on the tenure track are not equal for all assistant professors and to adjust accordingly.

If commitments to increasing faculty diversity are more than symbolic gestures, colleges and universities should address the systemic issues creating these racialized and gendered inequities. That is the only way to increase the number of tenured Black women in our colleges and universities.