You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

pepifoto/istock/getty images plus

We were stunned by the survey responses. Given higher education's current emphasis on critical thinking, why did students enrolled in introductory science courses feel so unprepared to analyze data, articulate research and consider implications? Why didn't students feel prepared for this kind of basic critical thinking work?

In 2018, we surveyed a cohort of STEM students at Pima Community College inquiring whether or not they felt that logic and critical reasoning skills should be taught in introductory STEM courses. The responses indicated that the students valued critical thinking, and they had practice with it in their more "subjective" humanities courses. But they all felt unprepared to use those skills in a science course. Students indicated that they were struggling to make sense of the primary and secondary research they were conducting, and even if they were more comfortable analyzing research, they said they would still feel incapable of articulating their findings and considering the implications. Most important, however, students felt that they were not the only ones having this problem. They claimed that most people don't know what it means to think critically.

While we are quite not as pessimistic as our students, we agree that not enough is being done in our colleges and universities to teach critical thinking skills, and that is having detrimental effects on our society. However, we also realize that thinking is only part of the problem. If students have a chance at tackling the complex challenges of the 21st century, they need a variety of critical skills.

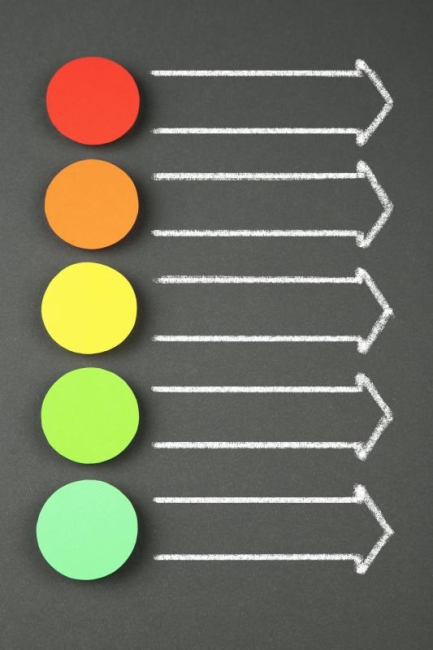

For that reason, we advocate for more holistic critical practices, which we refer to as the five essential ways of knowing:

#1. Critical thinking refers to a person's ability to evaluate data, make connections, and draw conclusions in a rational and unbiased manner. According to The Foundation for Critical Thinking, people capable of this kind of thinking adhere to universal intellectual standards and possess essential intellectual traits. And while we take exception to words like universal and essential for being exclusive and limiting, we acknowledge that the ideas for which these authors advocate are important. For instance, the intellectual standards include fairness, depth, accuracy, clarity and logicalness. Similarly, the intellectual traits include humility, autonomy, integrity, perseverance, empathy and fairmindedness.

Instructors in any discipline can implement critical thinking skills into their classes by first familiarizing students with these ideas and then engaging them in critical reflection about their own work. Questions as simple as, "Is that a fair assessment of the case?" or "Are we sure about the logic that moved us from data to inference?" invite students not only to arrive at an answer but also to evaluate how they got there.

#2. Critical feeling refers to a person's ability to both regulate and utilize their emotions to know more deeply. Cognitive psychologist Rolf Reber argues that students who have good emotional "hygiene practices" -- that is, students who take care of their mental health through spiritual ritual, physical exercise and regular relaxation -- are happier people who think more clearly and are easier to work with. In addition, the famous feminist author bell hooks argues that emotions aid students in the classroom because people who are emotionally invested in a topic tend to engage more deeply with it.

Most important to remember, however, is that rational and emotional thinking cannot be separated. Neurologically, our thinking and our feeling are integrative processes that take place in our limbic system. We couldn't separate our thinking from our feeling if we tried, so we need to learn to think and feel together.

Some instructors have found, for instance, that starting classes with breathing exercises and other mindfulness techniques helps students get into an emotional state conducive to learning. Moreover, all instructors can encourage critical feeling by choosing case studies that students find relevant and will be invested in, asking students to identify how they feel about course content, and using those emotions to build honest inquiry. Helping students recognize, understand and work with not only positive but also negative emotions such as fear is crucial for developing their critical feeling skills.

#3. Critical imagination refers to a person's ability to imagine worlds and experiences that are different from the ones in which they currently exist. Sociologist Ruha Benjamin argues that our society lacks critical imagination, and thus, we are unable to conceive of futures that do not reproduce the problems of the present. Her solution is to help students develop "radio imagination," a term she borrows from the science-fiction author Octavia Butler. A radio imagination hears possibilities and fills in the necessary details to make them a reality. Radio imagination asks us to listen for experiences, perspectives and possible solutions beyond the familiar. It asks us to imagine and work toward futures that might initially seem impossible.

Instructors may have difficulty practicing radio imagination in the classroom because few students have been challenged in this way. We have found it helpful to first ask students to research a variety of stakeholders, experiences, perspectives, and ideas so that they realize that the personal experiences and perspectives with which they are familiar are not the only ones. Then, we ask students to see what solutions and programs already exist.

Finally, we engage in expansive brainstorming and mind-mapping sessions before choosing the best solutions and figuring out how to enact them. For example, students in an environmental biology course might consider the earth or the ocean as their own stakeholders. Students could imagine what perspective and concerns these actors bring, research what solutions are already being pursued, and brainstorm how they can participate in those solutions.

#4. Critical engagement refers to a person's ability to discuss their ideas with others and to explain their reasoning. The ancient Greek philosopher Plato argued that a person can only demonstrate full reason and intelligence on a topic when they defend their ideas in reasoned debate. For Plato, debate took the form of dialectic, a kind of question-and-answer discussion format in which one person tries to poke holes in another person's argument. Through such a method of reasoning, the Greeks believed they could discover absolute truth. And while contemporary educators might not put as much faith in dialectic as Plato did, asking students to explain, and even defend, their ideas is a good way to ensure that their reasoning is logical and comprehensible.

Instructors can provide students with opportunities to practice critical engagement with other people through research presentations, peer-review sessions, and full-class discussions that ask students to present their thoughts, engage with the others, and evaluate arguments. The problem that many educators face, however, is getting students to engage critically in productive rather than destructive or apathetic ways. To avoid those issues, we suggest asking students to engage in presentations and discussions rather than debates. We also recommend requiring students to conduct research before discussions, assigning plenty of points for being active participants during discussion and empowering students to share honestly.

#5. Critical being was popularized by the educator and historian Catherine Broom and refers to a person's relationship to the world. Enlightenment era thinkers such as Rene Descartes and Thomas Hobbes stressed the importance of individual autonomy and responsibility -- a philosophical comportment that heavily influences contemporary Western views of the world. Yet critical being takes a new materialist view of the world in that it acknowledges that individuals are co-created by a whole host of other human and non-human actors. For example, someone's ability to critically engage with a text can be influenced by what they ate for breakfast, the ease or struggle of their morning commute, or the pleasant or stressful interactions they had with their family the night before. Cultivating critical skills means acknowledging all of the things that co-create who we are and how we think.

Instead of bringing critical being activities into the classroom, we suggest instructors show students the importance of co-creation before and after class when they are asking how they are, acknowledging their joys and struggles, and discussing their own feelings and experiences. These small interactions demonstrate to students how to take stock of their situatedness in the world, how it is influencing their thinking and how they can navigate through it. Once this groundwork is laid, instructors might ask students to consider what other factors are influencing the research they are conducting and what variables, perspectives, and ideas might be being left out of the discussion.

As you may have noticed, these five essential ways of knowing are not easy, and they require practice. An instructor cannot tell a student how to critically think, feel or engage and then expect them to reproduce the skill adeptly. Instead, students need sustained and focused practice using each skill in different contexts, with different topics, and with different people. In that way, the five essential ways of knowing are less like memorizing the state capitals and more like learning to play a sport or musical instrument. Instruction helps, but the key is practice and feedback.

Instructors who wish to cultivate the five essential ways of knowing in their courses should provide students with opportunities for intentional practice and reflection. They should create what compositionist Byron Hawk refers to as "the conditions of possibility" for these skills to develop. In other words, instructors should focus on developing assignments, activities, discussions and experiences that provide students with the chances to think, feel, imagine, engage and be in a critical and productive manner.

In short, the current emphasis on critical thinking, with its sole focus on rationality, does not account for the complexity of how humans know the world and the kinds of critical skills that our students need. We need to expand our definition of critical thinking to include these five essential ways of knowing: thinking, feeling, imagining, engaging and being. Moreover, we need to be providing students with practice in these different ways of knowing in every class so they are able to apply them to a variety of topics and situations.