You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

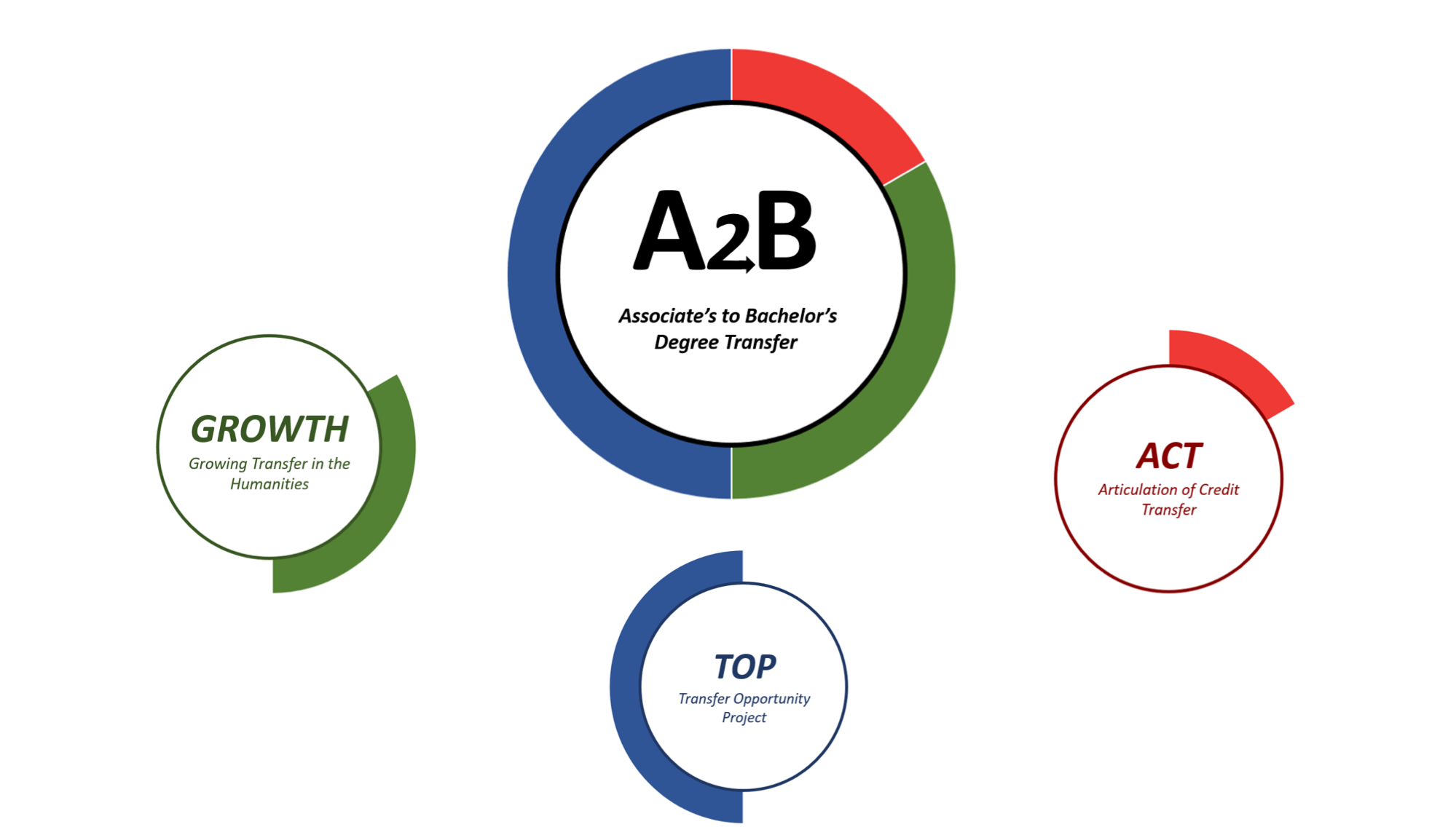

This piece introduces a series of posts to appear in the “Beyond Transfer” blog in the coming months. The series concerns the projects we at the City University of New York call collectively A2B, projects concerning associate-to-bachelor’s (vertical) transfer. A2B encompasses three groups of projects: TOP (the Transfer Opportunity Project, funded by the federal Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences), GROWTH (Growing Transfer in the Humanities, funded by the Mellon Foundation), and ACT (Articulation of Credit Transfer, funded by the Heckscher and Petrie Foundations). TOP and GROWTH are research projects. ACT is a program-improvement project. The forthcoming blog post series will describe TOP, GROWTH and ACT in more detail, including some of the distinct accomplishments of each (see also our four presentations at the 2022 NISTS virtual conference).

This piece introduces a series of posts to appear in the “Beyond Transfer” blog in the coming months. The series concerns the projects we at the City University of New York call collectively A2B, projects concerning associate-to-bachelor’s (vertical) transfer. A2B encompasses three groups of projects: TOP (the Transfer Opportunity Project, funded by the federal Department of Education’s Institute of Education Sciences), GROWTH (Growing Transfer in the Humanities, funded by the Mellon Foundation), and ACT (Articulation of Credit Transfer, funded by the Heckscher and Petrie Foundations). TOP and GROWTH are research projects. ACT is a program-improvement project. The forthcoming blog post series will describe TOP, GROWTH and ACT in more detail, including some of the distinct accomplishments of each (see also our four presentations at the 2022 NISTS virtual conference).

Importance of Vertical Transfer

Most of the readers of this blog will already be familiar with the importance of vertical transfer. It is the most common type of transfer. This is not surprising, given that over 30 percent of undergraduates attend community colleges (often for good reasons, such as the lower cost of these colleges), but a goal of 80 percent of community college students is a bachelor’s degree, which usually necessitates vertical transfer. Vertical transfer is also important for higher education equity. The associate degree programs at community colleges, on average, have a higher percentage of students from underrepresented groups than do bachelor’s programs, and thus anything that makes it harder for community college students to obtain a bachelor’s degree than for otherwise equivalent students who start college in a bachelor’s program differentially harms students from underrepresented groups. Unfortunately, only about 11 percent of community college students achieve a bachelor’s degree within six years of beginning college.

For these reasons, A2B has focused on vertical transfer. However, it is our hope that our findings and program improvements will benefit all types of transfer students, helping more transfer students complete all types of college degrees.

Assumptions and Principles of All A2B Projects

The A2B projects all operate within the same framework of assumptions and principles. The first assumption is that transfer by definition involves more than one college, and therefore challenges with transfer can rarely be solved by one college acting on its own—the sending and the receiving colleges both need to be involved for transfer to be effective. Therefore, mechanisms for improving vertical transfer must somehow reach beyond identifying and working with isolated motivated colleges.

A second assumption is that current incentive structures tend to favor colleges working for their own, including their own students’, benefit, not for the benefit of students intending to transfer out or for students at other colleges. For example, rankings and funding of a public college often depend on that college’s enrollment, and the graduation rate of its students who began there as freshmen, not on the ultimate success of that college’s incoming or outgoing transfer students. Again, this means that strategies to improve transfer must often transcend an individual college.

One way to go beyond single-college solutions is to make public—totally transparent—what happens when a student transfers from any college to any other college, and this is a deeply held principle of A2B. For example, this principle means making completely available to transfer students and those who support them (including faculty) information about how long it takes to get a response to a transfer application, how a student’s credits will transfer to a new college and how many transfer students actually graduate from a particular selective program at a new college. Having available this information will allow students to make optimal transfer college choices and can result in colleges competing to be chosen. Further, we in A2B believe that, by the very act of measuring and making public such information, colleges’ behavior will sometimes change in ways that benefit transfer students.

The ultimate guiding principle of A2B is that it should be no more challenging for a student to earn a bachelor’s degree by starting in an associate program at a community college than by starting in a college that offers only bachelor’s degrees.

Origins of the A2B Projects

The origins of the A2B projects reach back over 50 years to the many attempts of the CUNY Board of Trustees to pass resolutions designed to facilitate transfer between what are now 20 CUNY undergraduate colleges, enrolling close to 250,000 matriculated undergraduate students. These 20 colleges offer different types of undergraduate degrees—some offer only associate degrees, some only bachelor’s degrees and some offer both. Despite multiple attempts, as of 2010, the great majority of students were still leaking out of CUNY’s vertical transfer pipeline, with many credits being lost at the time of transfer. Therefore, in 2013, CUNY instituted Pathways, a set of policies designed to facilitate all types of student credit transfer. Although Pathways did increase the transfer of credits, it did not fix all of the transfer credit issues, particularly the transfer of major credits. In addition, there was not always compliance with the policy changes. Further, in the nine years since Pathways was fully effected, a time period that includes four changes in the CUNY system’s chancellor and six changes in its chief academic officer, a few policies have been reversed.

As of 2018, in addition to there being more work to be done on CUNY transfer, there was also not a great deal of knowledge about the national vertical transfer pipeline. Therefore, CUNY began the TOP project, a collaboration with MDRC, using CUNY as a laboratory to obtain information on vertical transfer. How, where and when do students leak out of the vertical transfer pipeline, what variables are associated with those leaks and how might the leaks be decreased? CUNY’s GROWTH project followed soon after, based on the hypothesis that, because there are fewer dedicated transfer programs for students in the humanities than for students in STEM fields, humanities associate-degree students might have more transfer challenges. ACT also began around this time, as a collaboration between CUNY and Ithaka S+R, with the specific purpose of directly helping CUNY transfer students, particularly vertical transfer students.

A2B Synergy

These A2B projects—TOP, GROWTH and ACT—are synergistic. One example of the synergy relates to how credits transfer. Until now, other than by reviewing transcripts one by one, researchers have only been able to determine whether credits transferred at all, not transfer credits’ applicability to general education, major and elective degree requirements. Having degree requirement applicability information is critical, because helping students transfer on time means ensuring that the credits that they transfer satisfy degree requirements, as opposed to becoming excess elective credits.

Therefore, early in ACT, we wanted to be able to see, at the moment of transfer, exactly where students were losing the degree applicability of their transferred credits. CUNY’s degree audit software (Degree Works) has a “fall-through” (excess elective credits) category, but Degree Works overwrites itself any time there is a change in a student’s record—it retains no history. This means that the fall-through category could not be relied on to tell ACT whether credits fell through as a result of transfer or for some other reason before or after transfer. ACT therefore started archiving, for cohorts of students, Degree Works information any time there was a change in a student’s record. Using this archive, ACT has now developed a dashboard that notifies advisers if a student, including a new transfer student, registers for a course that goes into the fall-through category, and TOP is using the archive to estimate credits lost at the time of transfer for its longitudinal analyses of the transfer student pipeline with a cohort of 2013 associate-degree students.

The forthcoming A2B series of posts in “Beyond Transfer” will provide more information about what we in A2B have already accomplished, and have not yet accomplished, in understanding and improving vertical transfer outcomes.

Alexandra W. Logue is a research professor at the Center for Advanced Study in Education of the City University of New York Graduate Center and the principal or co-principal investigator of each of the A2B projects. From 2008 to 2014 she was executive vice chancellor and university provost of CUNY, a system of 25 colleges and freestanding professional schools.