You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

It’s time to add OER – Open Education Resources – to a list of technologies (or technology resources) that might really be a catalyst for major change in higher education. Admittedly, it is still very early days here – the front end of the Gardner Hype Cycle fueled initially by the Peak of Inflated Expectations, followed by the Trough of Disillusionment, which leads into the Slope of Enlightenment, until we arrive at the Plateau of Productivity. (Remember the NY Times declaration that 2012 was the “Year of the MOOC?”) We’re a long way from the plateau with OER.

The basic OER arguments, offered with great passion by OER advocates and evangelists, are compelling. First, commercial textbooks are expensive. Second, OER offers a seemingly pragmatic strategy to provide “Day One” access to core course materials for students in critical gateway courses. And third, the absence of copyright and related clearance issues means that OER provides significant flexibility for faculty as they select and mix curricular materials from various sources for their syllabi.

No question that the OER messaging and movement are gaining ground. For example, almost three-fourths (72 percent) of the provosts/chief academic officers who participated the fall 2017 Provosts, Pedagogy, and Digital Learning Survey sponsored by the Association of Chief Academic Officers (ACAO) reported that they expected “OER to be a major source of curricular content in five years.”

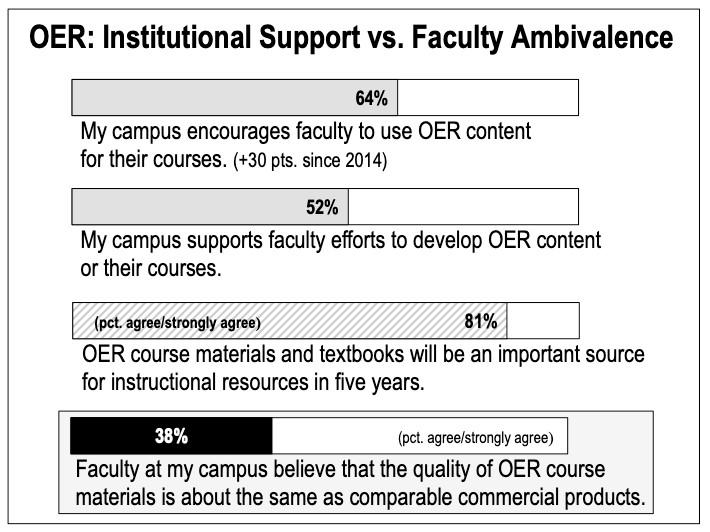

Among CIOs, the expectations for OER are even higher. Fully four-fifths (81 percent) of the CIOs participating in the fall 2018 Campus Computing Survey believe that “OER course materials and textbooks will be an important source for instructional resources in five years.” Concurrently, two-thirds (64 percent) report that their campus “encourages faculty to use OER content in their courses,” up 30 percentage points since 2014. Additionally, just over half the surveyed CIOs and senior IT officers report that their campus “supports faculty efforts to develop OER content.”

Overall, these numbers would seem to bode well for the future of OER.

However, it is individual faculty, not CAOs and CIOs, who make the decisions about course materials – and by extension, the use of OER materials in their classes. And there is evidence that faculty are far less enthusiastic about OER than CAOs and CIOs. Drawing again from the 2018 Campus Computing Survey, just two-fifths (38 percent) of CIOs report that faculty at their institution “believe that the quality of OER course materials is about the same as comparable commercial products.”

Too, the 2016 Going Digital Survey of some 2900 faculty at 29 two- and four-year institutions goes deeper into the faculty assessment of OER, and confirms faculty concerns about the quality of OER materials. At the time of the fall 2016, fully three-fourths (75 percent) of the survey participants had had no direct experience with OER materials: 15 percent were using OER course resources in their classes, and another 10 percent had reviewed OER options but decided not to adopt OER materials for their courses. Only a third (36 percent) of the survey participants agreed that “OER content provides a viable alternative to traditional print /commercial course resources.” In other words, a sizable majority of survey participants (64 percent) – some of whom had reviewed OER materials and many whom had not – did not believe that OER materials were comparable in similar commercial textbooks and other course resources.

So what might move faculty to OER? According to the Going Digital Survey, the top three catalysts for migrating from commercial to OER course materials would be:

- The high quality of OER materials (74 percent cite as important/very important);

- The low cost of OER for students (71 percent cite as important/very important); and

- The option to remix OER materials for the syllabus (65 percent cite as important/very important).

In aggregate, quality and cost emerge as the key issues in the OER conversation, followed by flexibility. This also plays out as choice vs. cost: (a) the prerogative of faculty to choose what they deem to be appropriate and high quality course materials vs. (b) the (often high) cost of course materials for students. Sometime these vectors align, but typically they do not (at least not now).

To date, it’s my impression (although I could be wrong) that much of the energy fueling the advocacy for OER has focused on cost, and by extension, Day One access. I’ve heard and read less about the “comparable quality” issues.

And there is also what I first described in November 2015 as the “apples vs. orchards” issue: the 1:1 comparison of a commercial vs. OER textbook is incomplete (and insufficient). The commercial product is part of an “instructional ecosystem” that includes a rich array of supplemental resources (test sets, online resources, etc.) and support services. And yes, these resources, prepared primarily for faculty, are paid for by students when they buy a new textbook. In contrast, OER textbooks typically are stand-alone entities that lack a similar bundled, “off the shelf” (or on the web) set of supporting or enveloping instructional ecosystem.

How, then, to advance the campus discussion about OER, one focused on and informed by merits of the materials? My suggestion is that we begin a “new and open” conversation about OER by stipulating the following:

- OER will reduce the cost of course materials for students; reducing the cost of course materials, specifically textbooks, is a good thing. Yes, textbooks and course materials are expensive. For calculating college costs and financial aid, the College Board estimates full-time undergraduates should budget about $1200-1400 for textbooks and course materials for the current academic year (2018-19). But as a corollary, let's acknowledge that arguments about how much money students “save” using OER may be inaccurate if not misleading, as the price comparisons are often based on the cost of a new (hardcover) text. The reality is that there are multiple price points for any one textbook – new, used, rented eBook, purchased eBook, actual use cost after buy-back – that determined the “price” of any one textbook. (See graphic below). Too, at $1400 annually for course materials, a single core text, if purchased new for $200, could consume as much as a seventh of an undergraduate’s book budget. But moving, on, let’s stipulate that OER texts and course materials will reduce the student cost of course materials.

- Day One access to course materials is also a very good thing. The concept is compelling: students should benefit when they have course materials in hand on the first day of classes. And there is even some evidence of impact: for example, a recent multicourse study at the University of Georgia comparing students who used commercial vs. OER texts suggests that Day One access may have some modest impact on academic performance (slightly more students with slightly higher grades) and may also slightly reduce DFWI numbers. So given a compelling argument and some early, if modest, supporting evidence, let’s stipulate that Day One access is a good thing – and move on.

- A free beer is not the same as a free puppy. This insight comes to us from the Open Source software movement, and references the experience with Open Source LMS applications Moodle and Sakai, and Internet-essential backroom applications such as Apache server software.A free beer is a static event. It’s one and done consumption; there are no acquisition or ancillary costs.In contrast a free puppy is a dynamic experience: although no acquisition costs, there are significant and continuing operating costs – financial (for example, food, vaccinations and a dog license) and otherwise (e.g., time required for the daily dog walk and monthly doggie bath). Admittedly, OER materials are not as cuddly as a puppy. But like a puppy, they may involve “operating costs” for students.For example, we know many students prefer to read print rather than on-screen.Consequently, printing OER materials provided free (or at very low cost) in digital format is a student cost, although far less than purchase price of a new, used, or digital commercial textbook. So our third stipulation is that students may still incur some costs for using “free” course materials.

Accepting the “three stipulations” means that we can now focus on quality: are OER materials as good (or perhaps better) than the similar commercial titles and supporting resources?

However, by focusing on quality the conundrum we now confront is that the assessment of quality is in the eye (and resides with the experience) of individual faculty.

One way out of this rabbit hole would be to draw on peer review: the faculty and departments that review OER materials when doing course and curricular redesign could make those reviews public. And it would be great if the departments and campuses that use OER would engage in routine, thoughtful, formal, and comprehensive assessments to compare the OER experience against the experience with commercial course materials. Campuses routinely post the results of their LMS reviews when they consider changing platforms. So why not post reviews of curricular materials – both OER and commercial??

Additionally, the campus, collaborative, non-profit, and quasi-commercial organizations that produce OER materials – including MIT’s Open Courseware, Lumen Learning, OpenStax, the Saylor Academy, among others – should commission thoughtful, thorough, and independent assessments. Evaluation should focus on student performance and the faculty experience with and assessment of the OER materials.

The assessment of student learning seems obvious.Yes, we want to know if students learn more (or better) using a commercial text or an OER text.

But attention must be also paid to the faculty experience with and assessment of OER materials.Why? Because faculty experience transition costs when they migrate to a new set of course materials, be they commercial or OER. And with OER, the transition costs may be higher than with commercial course materials because an “OER textbook” typically does not have the accompanying “instructional ecosystem” of ancillary materials typically provided by commercial publishers for core/gateway courses such as web sites, supplemental course materials, instructor guides, student guides, and test sets.(Remember the difference between a free beer vs. free puppy?)

Yes, I know that peer reviews and course compilations are available on Merlot and elsewhere. And these are great resources for individual faculty or departmental curricular review committees searching for alternatives to current texts or for course material to supplement their syllabi. However, data from the 2018 Campus Computing Survey reveal that barely a sixth (16 percent) of campuses routinely engage in any formal evaluation of their efforts at instructional innovation and digital pedagogy, which would include OER initiatives. We need to do more evaluation of efficacy of all course materials, and we need to do it better.

Consequently, if OER is to fulfill the promise low cost/high quality course materials – if OER is to advance on the merits of quality course materials – we need more and better reviews and assessments to aid and inform the OER agnostics and the OER antagonists about the educational efficacy of OER course materials. Opinion and epiphany will not suffice. OER advocates must provide both data about impact and narrative about the student and faculty experience to help advance their cause.

Disclosure: For the record, I view myself as an OER agnostic – hopefully a fair and thoughtful agnostic.

RELATED ARTICLES FROM THE DIGITAL TWEED ARCHIVE

== OER Issues: Apples, Orchards, and Infrastructure (Nov 2015)

== Recalibrating Expectations for eTexts (Jan 2012)

== Cars . . . and College Textbooks (Aug 2012)

Follow me on Twitter: @DigitalTweed