You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In a way, a university made me

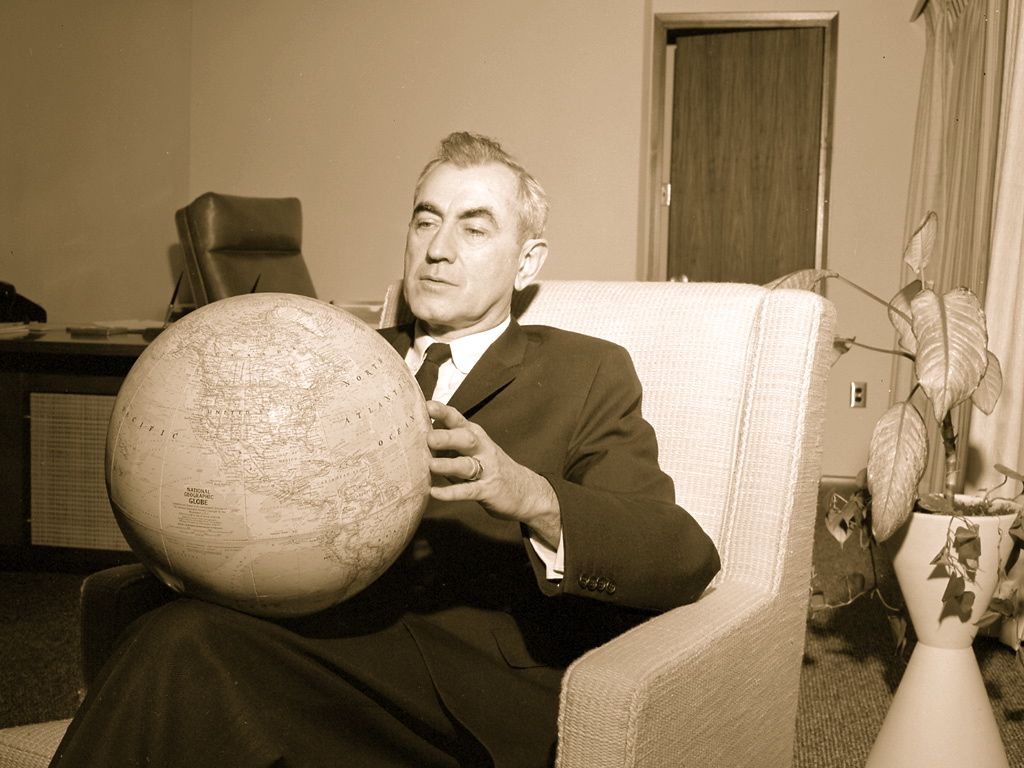

In the 1950s and ‘60s, President Delyte Morris grew Southern Illinois University-Carbondale from a normal school with 3,000 students to a university with 25,000. Under his ambitious leadership SIU developed schools of agriculture, engineering, law, and medicine; a second campus with 10,000 students was created a hundred miles away.

In The University That Shouldn’t Have Happened, But Did, Robert A. Harper explains how Delyte Morris’ brilliance consisted of “unorthodox practices that in many respects pioneered new dimensions in higher education,” including opening the “doors as widely as possible…to the people of [the] economically depressed region, to minorities and the physically handicapped, and to students from throughout the world. [B]efore there were community colleges [in the area] SIU offered courses in trades that were needed by the people of its region but were considered inappropriate for an institution of higher education.”

Morris used that momentum to offer courses at satellite centers, such as the Vocational Technical Institute, where my father began teaching as an instructor in 1955. Then Morris set his eye on “educational and vocational missions” in “developing countries on three continents.”

One of those countries was the Republic of Vietnam. It was the age of hearts and minds.

(Morris, below, flying the aspidistra. Photo courtesy Louisa H. Bowen University Archives & Special Collections, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.)

A 1962 report by South Vietnam’s Department of National Education says:

A 1962 report by South Vietnam’s Department of National Education says:

After nearly a century of foreign domination, Viet Nam has recovered her sovereignty. She is at the same time confronted with several urgent problems that affect her independence.... The key problem is to reconstruct the country and improve the underdeveloped economy so as to bring about employment to all. Up until the date of the recovery of independence, we must state that we had neither heavy industry nor light industry. We had to import everything needed for the people's livelihood, from simple household articles to items of machinery. [...]

Under the French period, Indochina had, like other colonies, the role of providing France with raw materials and importing nearly all manufactured products needed for the country. Therefore, the technical – vocational education that was organized by the decree of March 2, 1930, signed by the Governor of Indochina, had the sole purpose of training just enough workers to maintain and repair important pieces of equipment needed for the operation of the government. […] In 1955, in all Viet-Nam there were only two technical schools...two apprentice schools...three applied arts schools, and seven atelier-ecoles. Moreover, several schools were, partly or in whole, requisitioned for other purposes. […] The machines and equipment used for instructional purposes were too old and did not match the progress of our crafts and industries. Besides, there were not enough machines for all the students to use. […]

When the French turned over to the Government of Viet-Nam the technical-vocational schools, there was not a single full-fledged teacher or supervisor of shops of the local service in all the country.

This sort of idea must have struck Morris and others with great force. The region of Southern Illinois itself had its natural resources, especially coal, stripped by outside powers and was left with little political agency. It did, however, have technical and vocational expertise developed from the mining days, the WPA era, and WWII.

Under the flag of the US Overseas Mission (USOM), SIUC sent its first educational team to Vietnam in 1960. Funding would come from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), founded by President Kennedy in 1961. Until then, there was no single US agency responsible for all foreign economic development.

“There is no escaping our obligations: our moral obligations as a wise leader and good neighbor in the interdependent community of free nations...and our political obligations as the single largest counter to the adversaries of freedom,” JFK said.

“Isn’t that what we do everywhere?” George Carlin said 10 years later. “We free people and lay a little industry on them.”

“Many new schools, such as the National School of Commerce, the Phu -Tho Polytechnic School, and the Vinh-Long, Da-Nang, and Qui-Nhon Technical Schools were founded with funds from national and foreign aid budgets,” the South Vietnamese report says. The number of classes offered jumped from 27 in 1954 to 103 in 1961. Enrollment in those years went from 709 to 3,641.

“During the coming months,” the report says, “[the Phu Tho] school will receive additional American equipment valued at 160,000US$. A team of American professors has joined the school to strengthen the instructional program. It is planned that the school will open additional sections to provide training in ceramics, foundry, metallurgy, electronics, home economics, and business education. To help carry out this plan, it is expected that USOM will finance 30,000,000VN$ worth of additional building construction.... After this plan is accomplished, technical-vocational education in Viet Nam will have a model technical center, well-housed and equipped with the most up-to-date training equipment in all of South East Asia.”

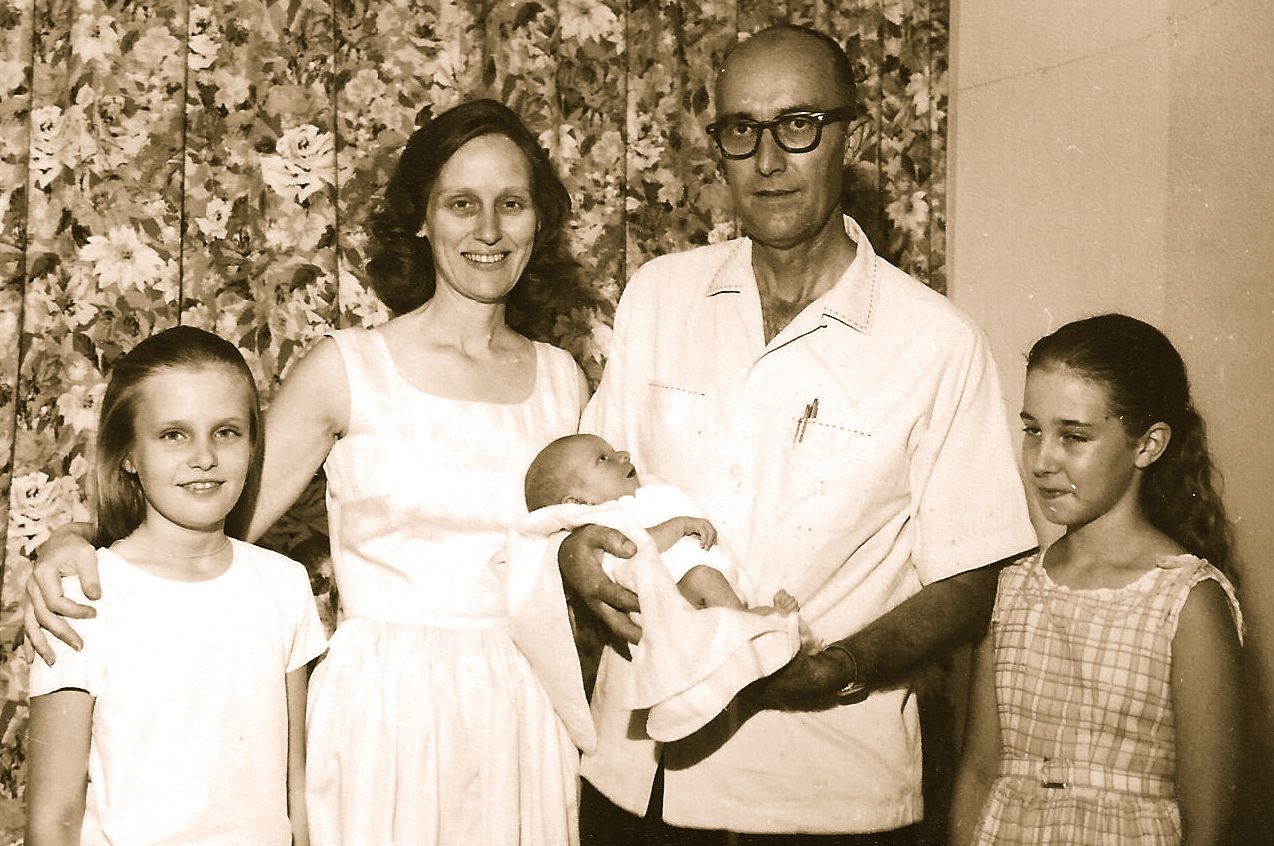

My father was one of the team mentioned, as he, my mother, and two half-sisters had left for Saigon with an SIUC team in late 1961.

We know others as we know birds on the wing

I never had much time with my father. Much of what I know of his life is mere data, but due to military service and employment, there’s more of that for him than for my mother.

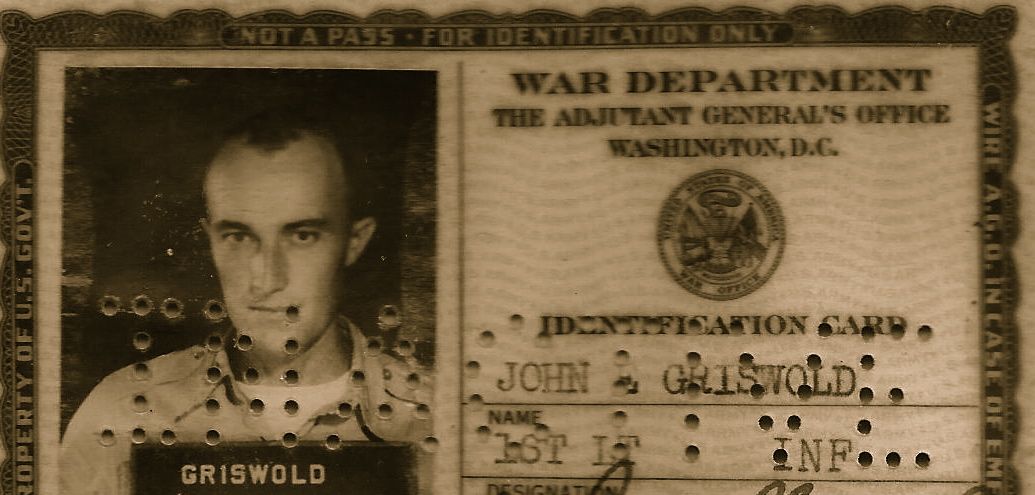

John Emerson Griswold was born in southern Illinois in 1918. He grew up there, in Walpole, a town founded in 1857 by his great-grandfather, Gilbert Griswold, Jr. Walpole was once named Griswold, as Gilbert was one of the first settlers, a surveyor, teacher, and the hamlet’s founding postmaster in 1832. The family came to America in 1639 and can be traced to 13th-century Warwickshire. John’s father, also Gilbert, was a sharecropper.

John Emerson Griswold was born in southern Illinois in 1918. He grew up there, in Walpole, a town founded in 1857 by his great-grandfather, Gilbert Griswold, Jr. Walpole was once named Griswold, as Gilbert was one of the first settlers, a surveyor, teacher, and the hamlet’s founding postmaster in 1832. The family came to America in 1639 and can be traced to 13th-century Warwickshire. John’s father, also Gilbert, was a sharecropper.

During the Depression, John joined the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to help support the family. By 1941 he was married and in the army. He served in the Pacific Theater with amphibious armored units in Hollandia, Port Moresby, Biak, Halmahera, Leyte, Lingayen Gulf, Borneo and Labuyan. He enlisted as a private, became a tank commander, and was responsible in the war for seven maintenance shops and 78 medium tanks and 140 supporting vehicles. He mustered out in 1946.

After the war, ’47-’50, he earned a BS with honors in three years at the University of Illinois. The following year he stayed on to get his master’s in vocational education. He did another stint in the army, ‘51-’53, in Panama, ended his service as a captain, then taught high school for the Panama Canal Company in the Zone and worked in the Cristobal shipyard. He and his wife had a daughter. He listed himself as a Lutheran and a Woodman of the World.

By 1960, when his first wife died of cancer, he’d been working five years at SIU as a teacher of metallurgy, welding, drafting, and shop technology. He was left with a young daughter, medical bills, and the memory of his wife’s suffering. He applied to jobs around the country. I can imagine him eager to get out, ready to move on to something new. He was a smart, tough man, hard, I suppose, in the way of those who’ve seen too much reality, and he was used to the most practical labor, which he’d used to serve his ambitions. He was looking to fix things, get them running.

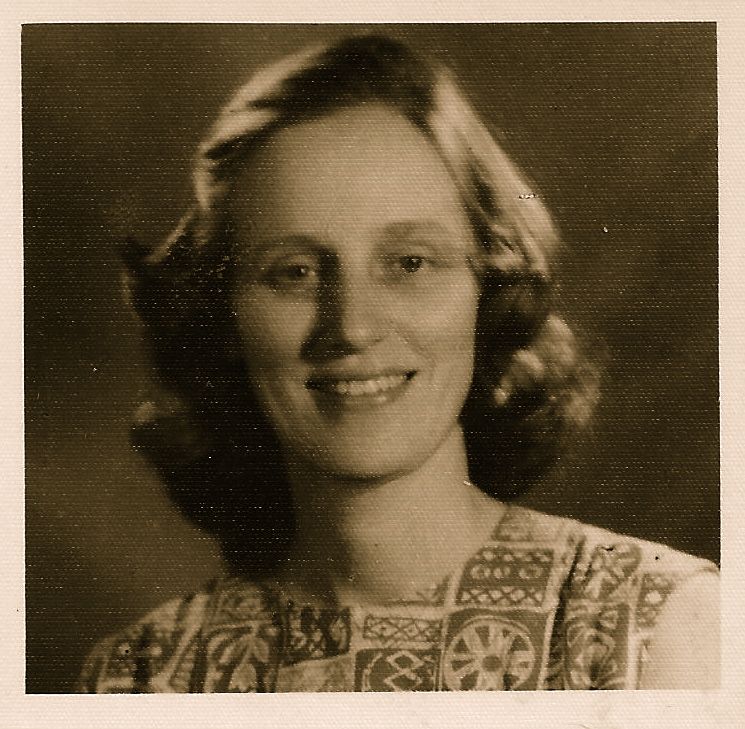

My mother, Helen Lucille Griswold, née Sneed, also grew up in southern Illinois. Much of what I know about her life is from stories she told. Born in 1920, she was the youngest daughter (“Baby,” to her father his entire life) of William J. Sneed, a state senator and UMWA subdistrict and interim district president. Sneed was born in 1883 and was for most of his adult life what I consider the best kind of rabble-rouser, fighting for working people’s rights and for community, though he got caught in dirty politics and may have done regrettable things. (My first two books are in part about those things.) My mom always insisted he was orphaned and worked in the mines as a boy. Whatever happened with his parents ruptured the genealogy, which for now ends at him.

My mother, Helen Lucille Griswold, née Sneed, also grew up in southern Illinois. Much of what I know about her life is from stories she told. Born in 1920, she was the youngest daughter (“Baby,” to her father his entire life) of William J. Sneed, a state senator and UMWA subdistrict and interim district president. Sneed was born in 1883 and was for most of his adult life what I consider the best kind of rabble-rouser, fighting for working people’s rights and for community, though he got caught in dirty politics and may have done regrettable things. (My first two books are in part about those things.) My mom always insisted he was orphaned and worked in the mines as a boy. Whatever happened with his parents ruptured the genealogy, which for now ends at him.

My mother was no doubt spoiled to the maximum degree possible in a little coal town two hours southeast of St. Louis. She attended Stephens College, learned to fence, took flying lessons, and drove a hot little 1949 Ford roadster, then a hot little Comet, then a hot little Thunderbird. (She always loved hot little cars.) She wanted to serve in WWII, but her Daddy wouldn’t permit it. She married twice before she met my father and had a daughter from her second marriage, the same age as his. My mom had a master’s in education too and had lived and worked in Chicago, south Florida, and elsewhere before returning to her hometown of 10,000 to teach elementary school to the sons and daughters of miners, factory workers, and the petit bourgeoisie.

She had ideas—feminism, internationalism, anti-war sentiments, notions of class and race—that made her life harder in that place and time. Her idealism included the belief that the male janitor at the school where she taught shouldn’t be allowed to harass female teachers by handing them a screw and saying, with a leer, Call me if you need me. If she were living now she’d see Bernie Sanders as the embodiment of the Sixties she once thought possible. She loved adventures, which to her meant going places, meeting new people, and learning things. She didn’t stay at jobs long. She was, I think, brilliant in perception, short on patience, and suffered no fools, gladly or otherwise. In short, she was a ship looking for a solid reef.

Of course they found each other.

They married in August 1961 and a month later were living in Saigon. Looking back through the hazy decades, I try to see what they each thought they would get from their time in Vietnam. For my father, it might have been the challenge of using his practical knowledge in a new place; the hot, humid climate, monsoonal weather, and smell of the sea that he knew from the war; the excitement of working against a new threat, now in the Mekong Delta.

For my mother it might have been some romance of the East, Bali Hai, James Michener and Rodgers & Hammerstein, the beauty of the Paris of the Orient.

They found it. They had it all. Challenge, adventure, new sights. Extra pay, arranged housing in an American-style subdivision, a maid, shared driver, and gardener. Fresh fruits and vegetables as they’d never seen; fresh fish, tea, and local coffee grown in the mountains near Dalat; bustling colorful fragrant markets; the warmth and hospitality of the Vietnamese people. My pigtailed sister had a pet monkey. My mother collected art. They were middle-class white Americans who had managed a late-colonial life.

I was born in Saigon, on Ho Chi Minh’s birthday. My mother said her doctor was a Vietnamese woman educated in Paris. The first scrip written for me is probably in her hand, on the stationery of Dr. Tran Dinh De, Ancien Fellow de la Johns Hopkins University de Baltimore (U.S.A.), Professeur d’Obstetérique et de Gynécologie à la Faculté de Médecine de Saigon, and the Republic of Vietnam’s Minister of Health.

I was born in Saigon, on Ho Chi Minh’s birthday. My mother said her doctor was a Vietnamese woman educated in Paris. The first scrip written for me is probably in her hand, on the stationery of Dr. Tran Dinh De, Ancien Fellow de la Johns Hopkins University de Baltimore (U.S.A.), Professeur d’Obstetérique et de Gynécologie à la Faculté de Médecine de Saigon, and the Republic of Vietnam’s Minister of Health.

A telegram from the American Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State, bylined Saigon, October 31, 1961, 4 p.m.:

...Dr. Tran Dinh De, level-headed Minister of Health, told Embassy officer Oct 29 that while GVN [Government of Vietnam] could continue resist Communists for while longer if US troops not introduced, it could not win alone against Commies.

While I'll follow the thread of my own family's fortunes, one wonders what happened to the doctor and his own.