You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Plank, Pull, Preen, Prick

by Sandra Beasley

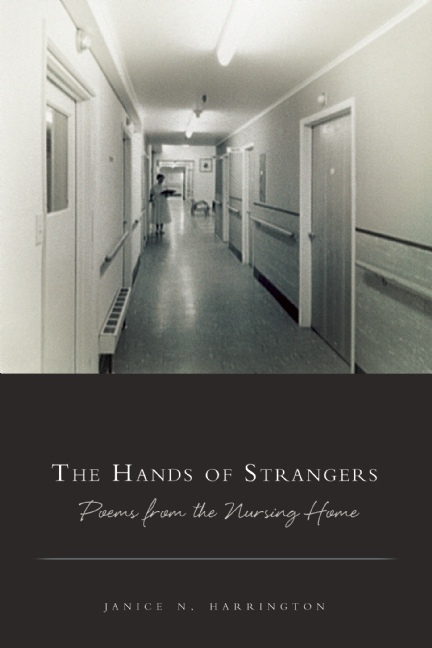

In her second collection, The Hands of Strangers: Poems from the Nursing Home (BOA, 2011), Janice N. Harrington turns an unflinching eye to the world of those who have reached a final stage of life. These portraits of patients and the power relationships they share with their caretakers are “visceral” in the truest sense of the word, driven by the perils (and the occasional pleasure) of the human body as it drifts, marches, or cannonballs toward breakdown. Wounds are opened, fault lines are revealed, and fluids unleashed.

For those wary of such a subject, there is no denying that at times the scenes are grim. But there are also moments of universal insight, grace, even humor. Furthermore, Harrington displays a level of craft and formal play that constantly engages the reader. In this respect I find myself particularly drawn to “Starch,” a prose poem featured in the second section (“Wards”). Here is the full text:

STARCH

For Donna

She was the human plank,

the slab, the level we lifted and lowered, hinging her narrow length on and off the bedpan, sponging the skin and removing the gown that sheltered a child’s drawing: stick arms, stick legs, a crayon-black triangle of hair.

We dressed her in gingham gowns, gowns with ribbons or delicate buttons, gowns splayed across atrophied muscle like a gingham bell ringing the handiwork of a diligent seamstress.

But it was not the hem’s tolling, not the empty pockets, not the pearl-dotted buttons that made her grieve but her flat and deflated sleeves. She complained, complained, complained until, coaxing and cussing beneath our breaths, we pinched the folds into pinnacles, into starchy cathedrals and stiff meringues.

Indurate, rigid, and rock, a woman who could move only her eyes and the tipmost knuckle of a still-pliant joint, she pulled the string that kindled the light, the light that drew us back to arthritic words pushed through a fence of teeth: fix the sleeves. We preened and pricked the sullen folds, bulged planes into globes, until at last, like her sleeves, we were schooled and shaped, billowing the cloth into lanterns and lungs of air, into cumulus and gingham balloons that rose and dragged behind their useless strings.

***

The poem opens with purposefully modest imagery. The ward’s withered body is juxtaposed with the bedpan, dressed in the innocence of not just any gown but ones adorned with buttons and bows. Audiences enter scenes of caretaking expecting the patient to be the victim; the very title of this book points to that premise. But in this poem the ward’s initial pose of vulnerability and objectification (she is described by her nurses as “the human plank // the slab, the level”) gradually transitions to one of power.

The poem opens with purposefully modest imagery. The ward’s withered body is juxtaposed with the bedpan, dressed in the innocence of not just any gown but ones adorned with buttons and bows. Audiences enter scenes of caretaking expecting the patient to be the victim; the very title of this book points to that premise. But in this poem the ward’s initial pose of vulnerability and objectification (she is described by her nurses as “the human plank // the slab, the level”) gradually transitions to one of power.

As it turns out, the patient does not want Pollyanna simplicity in her gown. She wants cathedrals and meringues; she demands a higher diction. In her insistence on controlling the state of her clothing, the patient does not pretend to be liberated from her body (even at the end the mortal form is characterized by “useless strings”) but she still attains a stubborn victory over her shepherds. They become the shepherded, “schooled and shaped” as the sleeves they are ordered to perfect.

The prose poem is a deft mode in which to examine these dynamics of structure. Overall the rules of syntax reign; sentences are respected in their organic, conversational integrity. But each stanza break here can be thought of as a pluck, an inflection of the language’s fabric for emphasis that mimics the literal subject. Meanwhile, in lieu of line breaks, heavy consonance (“She complained, complained, complained until, coaxing and cussing beneath our breaths…”) provides internal rhythms to the stanzas.

People often ask me about form in poetry. How do we know where to break a line? Where to start a new stanza? Where a rhyme is useful, and where is it sing-song? “Form should marry content,” I’ll answer.

That statement may seem a truism, but poems such as Harrington’s “Starch” remind me of its validity. Even the naked eye can see that each successive stanza of this poem gets longer, bigger, and by association “heavier” than the one previous. In a poem that opens with the speaker thinking in terms of lifting the patient, with each stanza break the patient—who evolves from stick figure to full flesh through sheer force of will—becomes harder to “lift” as if a mere inanimate plank.

Harrington’s collection will resonate with any writer who is interested in the wedding of style to theme, or who has examined the politics of the body in their own work. These poems will affect the heart of anyone who has faced the onset of aging in a beloved. In other words: everyone.

***

Janice N. Harrington is a poet, children's writer, professional storyteller, and former librarian. She teaches creative writing at the University of Illinois.

Sandra Beasley is the author of three books, including I Was the Jukebox: Poems (W.W. Norton, 2010), which won the 2009 Barnard Women Poets Prize.