You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

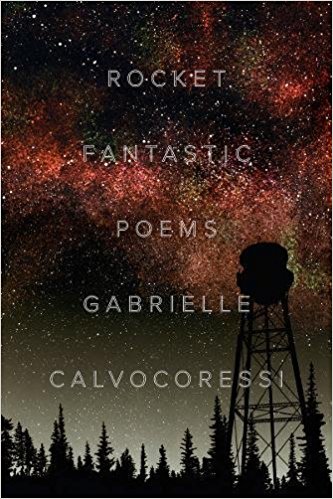

Rocket Fantastic. Gabrielle Calvocoressi. Persea Publishing, September 2017. $25.95

Review by Sean Singer

Rocket Fantastic is the distillation of one of the things poetry should be, which is a combination of confrontation and celebration. In a disturbing, yet profound way it pushes against, or perhaps “worries” whatever you think about gender and the body. We all have genders and bodies, but they frequently—at least for me— become background or setting. They obviously affect everything, but certainly I don’t think about them the way Rocket Fantastic does. The book, Calvocoressi’s third, is generous in how it does both critique and celebration, but on its own terms and in a way we have not seen before.

Using the shifting formats of a large-scale musical accompaniment in an unspecified musical genre, the book can’t be paraphrased. In the way that male and female energies differ within and without each other, this book’s energy is completely different. By turns haunting, funny, and raw, the book intends to show how self-determination is fluid; not in the sense of self-esteem, or self-actualization, but a kind of self-awareness of a human with a body (sometimes female, sometimes male, or neither) moves within spaces.

Using the shifting formats of a large-scale musical accompaniment in an unspecified musical genre, the book can’t be paraphrased. In the way that male and female energies differ within and without each other, this book’s energy is completely different. By turns haunting, funny, and raw, the book intends to show how self-determination is fluid; not in the sense of self-esteem, or self-actualization, but a kind of self-awareness of a human with a body (sometimes female, sometimes male, or neither) moves within spaces.For example, the first poem, “Shave,” introduces several of the ideas that appear throughout the book. One such idea is the metaphor of animals, especially deer, to emphasize the unnamable animal part of sex and sexuality, but also that mystery of transformation. The book quickly introduces a symbol that sounds like the quick intake of a breath, but refers to a gender-fluid figure, the Bandleader, who gives commands to the speaker, but is not either or both genders, and often is accompanied by the pronoun, “whose.” Calvocoressi’s invention, the symbol

shows the limitless possibilities of not just the Bandleader, but of how the speaker sees herself/himself as “unwritten.”

Other characters appear: Major General, a father, someone named T., and so forth. And throughout various animals from grubs to deer appear to infect, inspect, or critique how bodies might be just “nature,” something connected to the world, without artifice or subterfuge.

Bandleaders organize, “front”, or determine the direction of bands; one thinks of Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, or Sun Ra. In Rocket Fantastic, the Bandleader is variously a romantic partner, a landscape, a vision, a part of the wild, untamed self. Hearing Calvocoressi’s quick intake of breath for the Bandleader is haunting, almost dreamlike; because the reader is unfamiliar with how to approach them. They’re like the Philip Guston cartoon-like paintings of limbs on top of each other; they’re genderless, but they’re almost menacing, as if there are points where the speaker’s body and their body coalesce, meld, or rip violently apart. It’s quite disconcerting. There is no vehicle but poetry for such critiques.

Some readers will prefer the quieter, more narrative-based poems that look back, treating the past as mythology; those with the father and T. that move the lens away from the dreamlike state to something more like a memory. Structurally, these poems of softer lights serve in a way to tie the personal memory and the public or civic memories together. For example, in the crowd-pleasing “She Ties My Bowtie,” the tender moment shows two women quietly being nothing but themselves; but it’s also a way to show how the private becomes, especially in this age of horror and dystopia, part of the political economy. This poem is en face with “The Bandleader calls it the Angel Position,” a complete mastery of vulnerability and eroticism that really obliterates the twisted fantasies of the political and public knowledge of gender and sexuality. Here, the myth becomes less natural than it does supernatural.

Later in the book, animals appear more and more— not just the deer, but a fox, a lion, and creatures there are no names for, those on all fours, who reduce the distance between the couple and the reader. It’s intimacy both in form and content.

One of the most important qualities of being a writer is a kind of bravery. Rocket Fantastic has this above all else, and in a way that overflows, giving power to the limited and the denied; not only in terms of gender, but those of ideas. The poems resist those invisible structures upon which the political economy insists. To that end, the poems often have violence at their edges, as if an atavistic presence is there working in the background. Poems often play with tone to convey their meanings; others evoke a mood and nothing more; yet when have you read a poem that uses feelings almost as textures, coloring the background, and through which the speaker(s) peer through, are held down by, or escape from? Using emotion in a dimensional way is something this book advances and it’s something from which we could all learn a great deal. For example, in a late poem called “ ‘I was popular in certain circles’ ” a speaker almost like a maggot, who I imagine as Death, is so tiny as to be imperceptible, yet insinuates itself into the fabric of the environment. Both disturbing and giving relief, the poem shows how the master writer can bring forth not merely tone, but a world with its own consequences so alike our own.

A problem with a serious consideration of sexual, political, or environmental trauma like this book does, is that, even through the mechanism of metaphor, how do you either use space or some other device to make it palatable and clear? One solution in Rocket Fantastic is a penultimate poem that was circulating around the internets often when it first came out, “Praise House: The New Economy,” a poem that through praise takes the reader and assures her that everything will be alright. Essentially a list, the poem offers those simple pleasures without which the nightmare might seem unbearable.

Rocket Fantastic shows how it is possible to remain a person even though huge, often invisible systems are working and not sleeping to crush the person. Though they seem effortless, the poems must have been the end point of years of difficult and unforgiving work; they bring together private and public imaginations of what the body looks like; they show how the personal view of a body and its gender are so often free from a political oppression of those things even though we might not recognize that freedom. In-between spaces, in their mysteries, are kindled by these poems. They look the political economy in the eye both closely and further afield to show utter defiance. They show what possibilities could exist if we lived in a free society. We don’t, but we can in the poems.

***

Sean Singer’s first book, Discography, won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize, selected by W.S. Merwin, and the Norma Farber First Book Award from the Poetry Society of America. His second book, Honey & Smoke, was released by Eyewear Publishing in 2015. His work has appeared in Pleiades, Iowa Review, New England Review, and Salmagundi. He has a Ph.D. in American Studies from Rutgers-Newark and is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship. He lives in New York City. He has known Gabrielle Calvocoressi for more than 10 years.

Want articles like this sent straight to your inbox?

Subscribe to a Newsletter