You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

November 11, 2011: National and University Library of Kosova, Prishtina, Kosovo

By Charlie Hailey

It’s getting dark. We’ve walked from Prishtina’s Sports Complex, sitting next to the distinctive and heavily-graffiti’d sculpture of letters that spell “NEWBORN” in honor of independence, and across the communist-era Adem Jashari Square, where Marshal Tito’s Brotherhood and Unity monument (at right) lingers over a cluster of faceless sculptures, currently painted with the flag colors of NATO-member countries.

It’s getting dark. We’ve walked from Prishtina’s Sports Complex, sitting next to the distinctive and heavily-graffiti’d sculpture of letters that spell “NEWBORN” in honor of independence, and across the communist-era Adem Jashari Square, where Marshal Tito’s Brotherhood and Unity monument (at right) lingers over a cluster of faceless sculptures, currently painted with the flag colors of NATO-member countries.

Dusk flattens perspective and merges distant city lights with the nearly lightless campus grounds. Only the glowing domes and indirect lights of the library contour this oceanic expanse. Some say the 99 domes reference the white plis worn by Albanian men; another story attributes the geometries to Croatian architect Andrija Mutnjakovic’s hope for a unifying expression of Byzantine and Ottoman architecture. The architect originally conceived the building as the center of the University of Prishtina’s campus, but during the war, Serbian officials made the library into a military command center for two months in 1999.

An intriguing and sometimes vexing armature clothes the exterior, triangulated hexagons of aluminum plating forming a brise soleil to limit the sun’s intrusion. At night the library emits through this rigid netting a soft light, like the intellectual glow from a reading room. We pass the massive generator hanging from the library’s exterior piers, which makes even this small amount of light—so many faint stars reflecting off the building plinth—seem extravagant.

The head librarian has furnished the key, and once inside we see the card catalog that inventories current holdings and memorializes books removed and destroyed in the ‘90s. Yet the library survives when others—like many smaller Kosovar branches and Sarajevo’s main library—did not. In the carpeted silence we use the glow of our cell phones to search for the auditorium’s light switch. I wonder if this is my architecture colleague’s first glimpse of these spaces since being denied access in the ‘90s. As an ethnic Albanian, he and other students had to endure a parallel education, organizing curricula in Prishtina’s cafes and meeting for classes in homes on the city’s hilly outskirts. Public education forced into private spaces. And the resolute public institution of the library both testifies to this painful history and projects hope for the future.

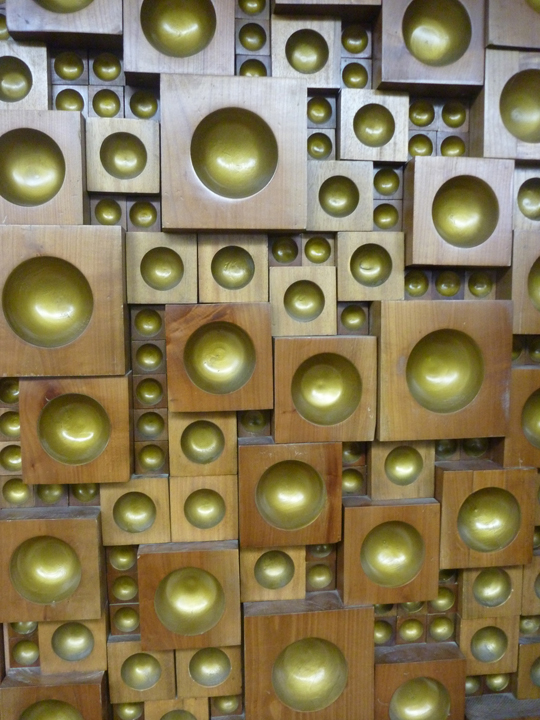

When the library’s auditorium is illuminated, at last, a thousand golden dimples are revealed on its walls--more than a thousand wooden cubes with hemispheric carved indentions. For me, each inlaid piece, each handmade inverted dome, thrillingly represents different aspects of the library’s holdings: Portraits of Kosovar poets, archival photographs of historic Kosova, Bill Clinton’s Prishtina address, a grand piano on a radiating marble floor, and the two million volumes that remain.

When the library’s auditorium is illuminated, at last, a thousand golden dimples are revealed on its walls--more than a thousand wooden cubes with hemispheric carved indentions. For me, each inlaid piece, each handmade inverted dome, thrillingly represents different aspects of the library’s holdings: Portraits of Kosovar poets, archival photographs of historic Kosova, Bill Clinton’s Prishtina address, a grand piano on a radiating marble floor, and the two million volumes that remain.

As we leave the library, my colleague tells me how for many years it was widely circulated among students that these books were retrieved by a man in a boat on a vast subterranean sea. He later learned that yet another danger perhaps accounts for the urban legend: Floods in the basement pose an ongoing risk to the library’s collection.

***

Charlie Hailey teaches design, theory, and history at the University of Florida. His research explores relationships among vernacular architecture, cultural landscapes, and experiences of home. His books include Campsite: Architectures of Duration and Place (LSU Press, 2008) and Camps: A Guide to 21st Century Space (MIT Press, 2009).