You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Editor's note: the guest entry below was kindly developed by Richard J. Edelstein and John Aubrey Douglass, Center for Studies in Higher Education (CSHE) - University of California, Berkeley. Richard Edelstein is a Research Associate at CSHE and Principal at Global University Concepts. John Douglass is Senior Research Fellow at CSHE. Their entry is based upon a longer paper recently published in CSHE’s Research and Occasional Paper Series (ROPS), which is available here. Please refer to the original working paper for all associated references. This ROPS contribution is part of the Center’s Research Universities Going Global research project.

Today's entry should be situated in the context of other informative attempts to develop an understanding of the modes and logics of internationalization -- see, in particular, Gabriel Hawawini's 2011 working paper 'The Internationalization of Higher Education Institutions: A Critical Review and a Radical Proposal,' NAFSA's work on 'comprehensive internationalization,' and the Cornell-specific (but very useful) 'Report from the Task Force on Internationalization' (Oct 2012). Kris Olds

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The International Initiatives of Universities - A Taxonomy of Modes of Engagement and Institutional Logics

by Richard J. Edelstein and John Aubrey Douglass

Like entrepreneurs in other sectors of our modern economy, many universities are in a rush to fill a relatively new and expanding market. Despite the significant increase in the number and type of international activities—from branch campuses, to MOOCs, and aggressive international student recruitment—many efforts appear to be launched without a clear idea of best practices or how specific activities might be productive and meaningful for a particular institution.

As part of a larger project based at the Center for Studies in Higher Education at the University of California, Berkeley, we have dubbed Research Universities Going Global (or RUGG), we offer a starting point for an analytical look at why and how, and at what cost, universities are engaging in an ever expanding variety of international ventures.

Here we briefly describe and categorize a range of actions and logics that are associated with efforts to respond to globalization and to develop the international dimensions of universities - a taxonomy of institutional actions that we hope to use and compliment by a series of case studies. What are the reasons and methods universities have chosen to become more globally active; how might we assess success or failure? What are the actual outcomes for nation-states that invite partnerships, and often provide significant initial financial support, on the quality and output of their higher education systems, on their labor markets, on their long-term economic development plans.

These are big and difficult questions that, thus far, have not been adequately studied. We hope to explore the answers to these questions and, via this taxonomy, promote others to study.

The Importance of Context

Three salient contextual variables help guide, inform, and condition the taxonomy of international engagement outlined in this article:

- The Academic Discipline

- The Level of Academic Study (e.g. 1st/undergraduate degree versus post-graduate degree)

- Institutional Prestige Hierarchy

Almost irrespective of the problem or issue under consideration, there is significant variability in the effects or outcomes when we consider the results in the particular context of individual disciplines or fields. The scholarly work, research methods, and organizational culture of the physics department are quite distinct from what is found in the economics department, the law school or the department of classics (Belcher 1989).

Level of study, course, or program also conditions how different problems are addressed. For example, study abroad and various mobility and exchange initiatives take on very different forms, durations, and pedagogies in an undergraduate/first-degree engineering program when compared with the same level of program in a foreign language or psychology department. Graduate students and faculty often have entirely different approaches to mobility issues because of greater individualization of instruction and research imperatives.

A final contextual variable worthy of attention is the prestige hierarchy. Not all colleges and universities are created equal and, like most social institutions, they compete with each other to achieve a high status or social value in society. More prestigious institutions, large or small, public or private, have certain advantages when it comes to advancing their mission and objectives. This appears to be true for international endeavors as well where some of the most active and successful institutions are prestigious and highly visible on global scale.

Historical Patterns and Contemporary Tensions

We have taken a distinctly sociological perspective that views the university as a social organization with distinct histories, structures, values, norms, traditions, and symbols embedded in the culture and that condition organizational behavior over time.

The research and writings of Burton Clark continues to shed light on what it is about the university that makes it distinct and exceptional in many respects. One of the key “truths” that Clark continually stressed in his work is that universities are inherently more decentralized and “bottom heavy” than other organizations such as business firms and most government bureaucracies (Clark 1983). Significant authority, both formal and informal, rests with individual faculty members and with departments, schools, and colleges. Institutional change is, to a large extent, dependent on the capacity of leadership to muster support from the ranks of faculty who are, in the end, the final arbiters of how teaching and learning occur and are the source of scholarship and scientific research, the two primordial functions of universities in society.

More recent research and publications by Georg Krücken also suggest that historically embedded patterns of organization and governance resist fundamental change and often marginally adapt themselves to evolving conditions of the larger environment and international trends and norms. Krucken shows, for example, how professors in Germany have largely retained their authority over academic policies in spite of the emergence of a larger administrative class and hierarchy (Krücken 2011, 2013 forthcoming).

John Aubrey Douglass has considered recent changes in research university organization that appear to take on forms of university devolution with increased fragmentation of the structure and the values that have historically held the university community together (Douglass 2012). Trends toward treating various schools, centers, and departments as profit centers with greater managerial autonomy or privatization options (often linked to neo-liberal and market-oriented management philosophies) suggest that changes in university organization and governance will make it increasingly difficult for university leaders to shape institution-wide strategies and policies that depend upon a robust set of shared values, beliefs and institutional loyalty. International strategies and initiatives become even more challenging should these trends prove to be persistent over time.

While there may have been some significant changes driven by technology, political demands, and the nature of teaching and research that have made inroads into the all-encompassing authority of faculty, it is difficult to imagine significant institutional change in universities that does not come with the advice and consent of individual faculty members.

Calls for a more entrepreneurial and economically relevant university and increasing tendencies toward adopting management practices and decision criteria from business are too significant and numerous to ignore. Nonetheless, efforts to embark on projects of substantial change often fail when they are implemented in a top-down and centralized decision structure.

In the end, most meaningful and successful change in the university occurs when the decentralized nature of the organization and the significant formal and informal authority of faculty is recognized and incorporated into the decision process in real and meaningful ways.

This essay and its presentation of clusters of activities, modes of engagement and institutional logics focuses wholly on the perspective of the individual institution and offers an alternative set of concepts and categories to describe and analyze institutional behavior and change. The purpose is to build on previous efforts and contribute a meaningful and relevant approach to thinking about issues and problems faced by university leaders as they make strategic choices about which international and global policies, programs, and relationships they pursue.

Clusters and Modes of Engagement

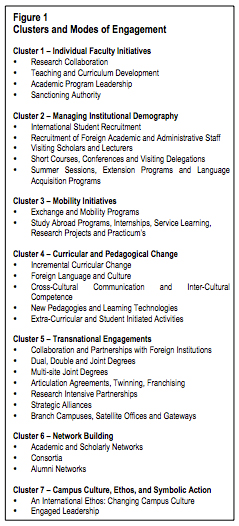

The taxonomy of actions and logics is conceptualized as a list of modes of engagement that can be organized into seven clusters of activity – see Figure 1. Clusters include individual faculty initiatives; the management of institutional demography; mobility initiatives; curricular and pedagogical change; transnational institutional engagements; network building; and campus culture, ethos, and leadership. Within our larger paper, we describe these various clusters and modes. Here is an example of how we portray Strategic Alliances:

The taxonomy of actions and logics is conceptualized as a list of modes of engagement that can be organized into seven clusters of activity – see Figure 1. Clusters include individual faculty initiatives; the management of institutional demography; mobility initiatives; curricular and pedagogical change; transnational institutional engagements; network building; and campus culture, ethos, and leadership. Within our larger paper, we describe these various clusters and modes. Here is an example of how we portray Strategic Alliances:

Alliances can be thought of as partnerships that evolve into more strategic and intensive collaborations across a numerous activities or functions. Shared faculty, student mobility, shared alumni bases, joint courses and degrees, joint research, and a common branding or marketing strategy are common elements of a strategic alliance.

There are few examples of successful strategic alliances. This is probably due to the challenges of developing partnerships where the benefits of greater collaboration or integration outweigh the costs or risks of potential problems. Concerns about a weakening of institutional identity, legal issues such as intellectual property rights, financial regulations, liability problems and governance systems, alumni relations issues, faculty and staff compensation and benefits issues, etc. must be resolved. Differences in institutional traditions and culture are often the most difficult to overcome. For all of the allusions to the “global university” and emergence of a global market for higher education, universities are still firmly embedded in nation states, national cultures, and institutional traditions that retain significant influence over how and under what circumstances they can change and engage in relationships with institutions and nations outside their home base.

There are a few examples of successful partnerships that have grown in intensity and breadth and have sustained themselves over time sufficiently to be considered alliances. These alliances, however, are limited to one major field or to a set of mostly natural sciences and engineering disciplines:

- INSEAD-Wharton Alliance - Launched in 2001, the Alliance between the Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania and INSEAD Business School in France and Singapore combines the resources of two world leaders in management education to deliver top-quality company-specific and open-enrolment programs to executives across four dedicated campuses: Inseam’s in Fontainebleau (France), and Singapore and Wharton's US campuses in Philadelphia and San Francisco.

Renewed for a further four years in 2008, the Alliance is an opportunity for MBA and PhD students to study across three continents. It also brings together the large and active alumni communities of both schools. The INSEAD-Wharton Centre for Global Research & Education fosters deep collaborative relationships across the two schools and encourages exchange of faculty and doctoral students. See http://about.insead.edu/partnerships/wharton_alliance.cfm.

-

Singapore-MIT Alliance (Agreement between MIT and the government of Singapore) -

MIT and its faculty have been engaged with Singapore for decades. The first large-scale institutional collaboration, the Singapore-MIT Alliance, was launched in 1997. Since then MIT and Singapore have engaged in on-going collaborations in research, education and innovation. The relationship has yielded hundreds of joint research publications, scores of joint research collaborations and curricular and research innovation at MIT and in Singapore. The following outlines a number of the joint projects that have come out of this alliance:

- Singapore-MIT Alliance. Founded in 1998, the Singapore-MIT Alliance is an innovative engineering and life science educational and research collaboration among three leading research universities in the world: the National University of Singapore (NUS), the Nanyang Technological University (NTU), and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

- Singapore-MIT GAMBIT Game Lab. The Singapore-MIT GAMBIT Game Lab, is a collaboration between the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the government of Singapore, was created to explore new directions for the development of games as a medium. GAMBIT sets itself apart by emphasizing the creation of video game prototypes to demonstrate our research as a complement to traditional academic publishing.

- Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART) Centre. The Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART) Centre is a major new research enterprise established by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in partnership with the National Research Foundation of Singapore (NRF). The SMART Centre serves as an intellectual hub for research interactions between MIT and Singapore at the frontiers of science and technology.

- Singapore University of Technology and Design Partnership. On January 25, 2010, MIT signed a formal agreement to help launch Singapore's new publicly funded university, Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD). MIT faculty will help develop new curricula and conduct major joint research projects, as well as assist with early deployment, mentoring, and career development programs. MIT President Susan Hockfield said of the collaboration, “It will give MIT new opportunities to push the boundaries of design research. MIT is fully committed to helping SUTD achieve its distinctive vision.” See http://global.mit.edu/index.php/initiatives/singapore/projects/

Institutional Logics

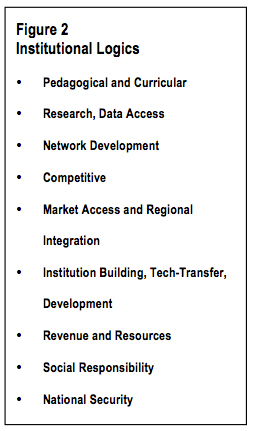

Why do universities embark on new projects and activities that engage the institution outside of its national boundaries? What motivates individuals and their institutions to include transnational relations among their core strategic interests and concerns when considering the future path for success? Why are more foreign students and faculty recruited and why are curricula and research agendas more international and global in scope? These trends undoubtedly have multiple and complex causes. We outline a set of nine Institutional Logics outlined in Figure 2.

Why do universities embark on new projects and activities that engage the institution outside of its national boundaries? What motivates individuals and their institutions to include transnational relations among their core strategic interests and concerns when considering the future path for success? Why are more foreign students and faculty recruited and why are curricula and research agendas more international and global in scope? These trends undoubtedly have multiple and complex causes. We outline a set of nine Institutional Logics outlined in Figure 2.

Again, in our attempt at brevity, we offer here our discussion of only one of the Logics: Market Access and Regional Integration Logics.

Recently, the Dean of Yale School of Management announced a new international strategy to create a network of partner business schools in countries with rapid economic growth and new business investments. These relationships, it is hoped, will provide opportunities for students and faculty to engage with their international counterparts to create professional networks that provide learning and research experiences as well as potential business opportunities in the future (Korn 2012).

The global economy is increasingly linked to emergent economies such as Brazil, Russia, India, and China (sometimes referred to as the “BRICs” in the US). It is not surprising that numerous universities in Europe and North America appear to have targeted these countries as high-priority locations for the development of relationships, activities, and programs. The logic seems to be that these countries will increasingly be influential in world affairs and, thus, establishing relations with local institutions and professional peers will create long-term benefits for attracting students and faculty as well as pursuing research agendas and fund raising opportunities.

In Europe, the Bologna reforms, and other initiatives that encourage greater integration of educational and research systems, stimulated the creation of numerous partnerships, alliances, consortia, and networks of universities between and among European institutions. Bologna’s creation of common degree structures and common academic credit and records systems go a long way towards the creation of a region-wide education space that can contribute to the construction of the regional economy as well as political and social networks that cross national boundaries. Recent efforts to develop common quality, accreditation, qualification and professional licensing standards are also linked to a desire for further integration of national systems and the creation of greater mobility in labor markets. The logic of regional and transnational integration coming out of Bologna appears to underpin many of the international projects and initiatives of European universities across a broad range of countries.

Recent European Union investments and policies in support of the Erasmus Mundus Program recognize that relationships with nations in other world regions (especially those that are emerging as key potential trade partners in Asia, Latin America, and Africa) remain important as well. The complex global economy requires the parallel construction of regional and global networks and European institutions thus have multiple logics that can justify greater international engagements.

One can also observe regional and market access logics in other areas of the world. The Southeast Asian region has numerous regional cooperation regimes and associations that encourage varying degrees of collaboration and integration. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) created in 1967 has encouraged regional cooperation in the economic and political spheres, but has also encouraged a range of initiatives in the social and educational sectors. The ASEAN University Network (AUN) functions as a vehicle for inter-university collaboration and regional higher education integration. In addition to regular meetings of rectors of member universities, AUN has activities related to credit transfer regimes, quality assurance processes, and academic programs in Southeast Asian Studies. It also serves as coordinating body for mobility agreements and scholarships with countries and regions outside Southeast Asia (e.g., the Erasmus Mundus Program of the European Union and a Chinese government scholarship program). See http://www.aun-sec.org/.

East Asia has significant student mobility in the region driven by geographic and cultural proximity. Increasingly, large numbers of students from Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan are attending universities in China and vice versa.

Australian universities are among the most active in recruiting international students from Asia and in establishing partnerships and satellite operations in the region. A regional and market access logic appears to underpin many Australian initiatives in the Asian Pacific region.

A Gaping Void in Research

As international engagement has become more central to the life and success of the university, we must expand our knowledge on the range and variety of these engagements, how and why institutions make the choices they do, and determine the patterns of success and failure. While universities have long been active internationally, many recent initiatives are relatively untried and extremely entrepreneurial. As discussed here, internationalization intersects with many strategic and core issues faced by higher education institutions everywhere.

Using the concepts of cluster of activity, mode of engagement, and institutional logic, we attempted to provide a useful analytical tool for describing the range of actions and behaviors related to international initiatives undertaken by universities and other higher education institutions. Hopefully, it will stimulate debate and discussion about how we can better observe, describe, and analyze the institutional behavior of universities in ways that are meaningful for scholars as well as practitioners.

It is important to look at the broader literature on higher education as well as the social sciences and the humanities for inspiration on how to conceptualize our research and to recognize that international and global realities have become a core strategic concern of the university. Rather than being a social movement that exists at the margins of the institution, international engagement, transnational systems, and global perspectives are now seen as crucial to institutional survival and future success. Connecting our research on the international dimension to broader institutional issues and a less narrowly defined scholarly domain will make it more relevant, intellectually rich, and insightful.

In the final analysis, the international initiatives of higher education institutions are best understood as part of a larger process of institutional change driven by multiple pressures and tensions to adapt to the changing economic, political, and social conditions affecting them. Much of the research on internationalization and comparative education analyzes regional and national policies and problems. Analysis at the institutional level is less common and perhaps more challenging given problems related to access to data and issues of confidentiality. Nonetheless, it is at the institutional level that we can obtain some of the most powerful insights into the organizational impacts, governance issues, and effects on teaching and research inherent in the growth of these activities.