You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Svetlana Shkolyar is a PhD candidate at Arizona State University researching astrobiology (life detection spectroscopy techniques for Mars). She is also an ASU/NASA Space Grant Fellow developing astrobiology classroom lessons and a science news tweeter for SAGANnet.org, a grassroots astrobiology community website.

“There are two types of speakers. Those who get nervous and those who are liars.”

― Mark Twain

I felt more nervous delivering a 3-minute science communication competition speech to an audience of Trekkies and Batmen (I was at ComiCon, if you haven’t guessed) than I did giving a real conference talk to a group of instrumentation experts from all over the world.

I’d given a conference talk to a group of graduate students at a pre-conference student seminar before, but this one was my first true conference talk. There stood little ol’ me in front of a bunch of judgmental experts who, by my calculations, had centuries of combined experience in my field.

I dread talks like most people dread root canals. I usually get up to that podium over-practiced and under-confident.

But once I got up there this time, magically, I felt calm and confident. I delivered without loosing my flow. I was even composed when I answered questions.

When I finished the talk, my mind filled with questions of my own. Why did I spend a week preparing for a 10-minute talk?! Why had I been up since 6am again?! Why did I choose to cut a fabulous dinner at the heart of St. Louis’ cultural district short so I could squeeze in one extra practice?!

Because science is about head-butting the boundary of knowledge of some obscure topic that only about 40 humans total, most of whom are sitting in the audience of your conference talk, currently understand. And to give a talk means you have head-butted successfully. According to a cracked.com article about the absurdity of grad school that I highly recommend reading:

Entering a postgraduate degree means declaring that you will become the world authority on something. Only a tiny bit of a specific section of a sub-discipline of something, but you will know that bit better than everyone else who has ever lived. Because nobody knew it until you did. You’re pledging to permanently expand the sphere of human knowledge by choosing a direction, learning right up to the bounds of understanding, then head-butting them further out with what’s in your skull.

Before you can head-butt your way into the frontiers of the unknown and display that in front of an audience, you must give yourself a few headaches from the nine all-nighters you spent in the lab pulling together that one magnificent plot you zoomed through in four seconds in your talk.

Once I finished my talk and sat back down, I realized that no one had challenged me, no one told me my data was wrong, and no one threw tomatoes at me. Aren’t those the things we all fear might happen during the dreaded conference talk? Well, they rarely do, because science isn’t cutting-edge and controversial and theory-shattering—at least not usually at the graduate student level. I have to remind myself of that; I now remind you of that.

I also realized something else after my talk. My field (the applications and optimization of an instrument for chemical identification about which I won’t bore you) is undergoing a revolution! I should be proud that I was one of 100 people contributing to that revolution of making our instrument more powerful. I finally felt like I belonged in that group, that I wasn’t just an impostor. And giving the talk solidified that feeling.

Thirty years from now, I will see where the field will be and think back to my first real conference talk when I was in grad school. And I will laugh at the clumsy, obsolete, and almost arcane science I presented back then, the way you laugh at your parents for using MS-DOS mode and your older brother for playing Nintendo on an 8-bit console. I took tedious point spectra instead of 3D mapping my sample?! I used what software to match my peaks?!

My point is, conference talks require two things: confidence and perspective.

Confidence is something that comes with practice and experience in your field. You will be able to talk about your work much more effectively in your third year of graduate school than in your first.

And that leads to the second thing: perspective. Don’t let reality get lost in your fears. If you’re a first-year grad student, your talk won’t be perfect. Expect that. Just don’t be afraid to do your best and be confident. No one knows your data better than you do, because you took it. Fake it until you make it! State your limitations. Be honest. No one will penalize you for it. Not even Trekkies and Batmen.

If you want some tangible tips on giving talks, here are some of my favorites:

1. A recent GradHacker post on managing public speaking anxiety

2. Amy Cuddy’s Fake It ‘Till You Become It TED talk and blog

4. Great tips on what to do 15 minutes before any presentation

5. A blog on overcoming nervousness by PsychologyToday

Do you have presentation anxiety? What are your strategies and tips for overcoming it? We’d love to hear from you in the comments!

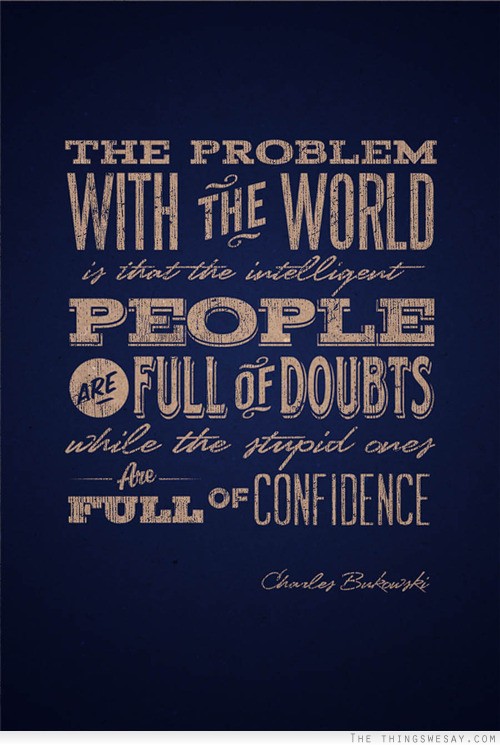

[Image via The Things We Say and used under the Creative Commons license.]