You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Natascha Chtena is a PhD student in Information Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. You can follow her on Twitter @nataschachtena.

Coursework is an essential part of any doctoral program, and it sets the stage for the dissertation phase. How essential it is I’m only realizing now—just when I’m about to be done with it.

As I’m approaching the end of my PhD coursework, I’m finding myself in a “coulda woulda shoulda” situation, reflecting on the many things I could have done differently and, ultimately, better on my road to the written qualifying exams.

What advice I would give to new PhD students (and my younger self)?

-

Learn how to speed-read. It might take a lot of effort at first, but it will save you time and frustration. New PhD students are treated like experts in “how to be a student.” Knowing how to read is assumed to be part of that. But many of us don’t. I mean, not really. During my first few quarters I was really trying to read everything that was assigned in my classes, until I realized (too late) that the point wasn’t to literally read everything. The point was to familiarize myself with authors and arguments and situate them within broader contexts, and for that I didn’t have to read 500+ pages a week line-by-line. While over the years I’ve become a faster reader, I wish I had invested time and effort in speed reading training at the beginning of my PhD.

-

It’s never too early to get started with citation management tools. For the first year at least I took notes all over the place, misplaced some, and lost others. It took me more or less a year to develop a note-taking system that works for me and that is sustainable. It took me another year on top of that to start using citation management software. Looking back, there’s so much information that got lost along the way. Today I keep everything (including notes and annotated PDFs) on Zotero, but I can’t help fantasizing about the repository I would have built if I’d started in my first quarter (yeah, wishful thinking).

-

There’s no such thing as a useless methods course. There’s no such thing as too many methods courses. Therefore, if given the choice, choose a methods course. When I started out, everyone insisted that as part of my dissertation preparation I take as many methods courses as possible. Familiarity with a breadth of methods was supposed to make me a better researcher and more attractive on the job market, and to open up opportunities for collaborative, interdisciplinary research. I wasn’t sold. And so I largely ignored them, until I realized that methods training is not just about me and my dissertation or the kind of job I want after I graduate. It’s also about developing the ability to understand and critically evaluate other people’s research, ask the right kind of questions at conferences, peer review manuscripts, and offer constructive feedback to my colleagues. And that’s an essential part of being an academic (granted, if that’s what you want).

-

Research Apprenticeship Courses (RACs) are at least as useful as “regular” classes. As a first-year without a clearly defined research topic or a polished scholarly identity, the idea of joining a RAC (your university might have a slightly different term) or an informal research group terrified me. But as I progressed through the program, I realized how few opportunities there were to present my work and get substantial feedback. In “regular” classes, one is asked to respond to specific readings and to produce assignments that relate to the objectives of a specific course, defined by an instructor (as opposed to the student). In research groups, members have to carve out an academic identity for themselves, which is more challenging, but also, perhaps, more important.

-

Be selfish. Make course assignments about you. It’s ok. Treating every single assignment as a potential dissertation chapter is, I think, an ambitious plan that only a handful of prospective PhDs realize. But every end-of-term assignment should somehow contribute to your larger project. If you can pilot research projects in your classes towards what you want to do your dissertation on, do it. If you can work on different aspects of the same project in different classes, do it. If you can rework older work to develop something presentable at a conference, do it. If you’re taking a course that feels irrelevant to your work, write a literature review or do an annotated bibliography. If your professor fights you, try (politely) fighting back. Don’t write random analytical papers you will never use or develop further just to please some professor.

-

Stay open-minded. What you think is useful or relevant will (probably) keep changing for a while. Everyone is, at some point during their PhD, forced to take some class they really don’t want to take. Over the past few years I walked into quite a few classes thinking they would be irrelevant or even useless. But I shouldn’t have been so quick to judge (and I really should have taken better notes!). Sure, there are classes whose value I still have to figure out (and maybe never will), but there are also classes that surprised me and others whose relevance became apparent many months after I delivered that final paper.

-

Oh, and keep the syllabi on file. They are incredible resources full of cherry-picked readings in areas you will want to revisit, whether for your qualifying exams, articles, dissertation or, further down the line, your own classes.

What advice would you share with students starting out with their PhD coursework? Are there things you wish you had done differently? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

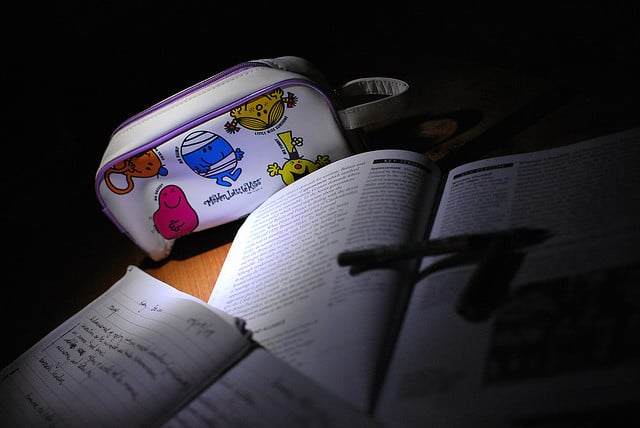

[Photo courtesy of Flickr user tommmmmmmmm and used under a Creative Commons license.]