You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The notion of a "flipped classroom” — students watch recorded lectures outside of class and participate in active learning during class meetings — has gained significant attention in recent years. It's an appealing notion in that it satisfies those who seek to promote active learning in higher education as well as those who feel strongly that the traditional physical classroom should remain the focus of learning.

But as historian Shane Landrum writes, there is a steady rise in hybrid and online courses and there is a need, especially in the humanities, for discussions about how to create active, student-centered online learning environments. Online classes are preferable to many students for a range of reasons, including distance, work, and family obligations. Now is the moment to explore new learning opportunities and to debate what we learn along the way.

In a series of three blog posts, we will share lessons learned about what online learning environments can offer students. Thinking beyond the MOOC-related hype, what opportunities exist in online education? Does online education push us to rethink and re-envision our approach to teaching and learning? How do we take advantage of online classes for teaching history?

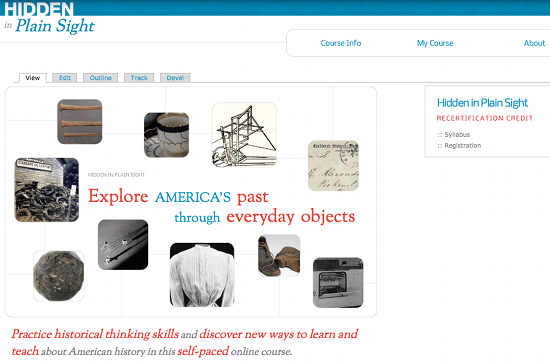

These reflections are based on our experience developing online, asynchronous history courses, such as Hidden in Plain Sight, for K-12 teachers.

In the past three years, more than 300 teachers have registered for these courses and the completion rate is over 95 percent. The feedback has been consistently positive from teachers who have called the courses “thought-provoking,” “meaningful,” and “eye-opening.” These courses were designed for a particular audience and to address targeted content and skills, but the lessons learned can inform new approaches and new possibilities for online learning.

Hidden in Plain Sight centers on inquiry-based learning rather than content delivery. While teaching the “what” of history remains an important goal, these courses are designed to make visible to participants how historians think about evidence and construct arguments. The course provides participants the opportunity to actively engage in this kind of historical thinking through examination of historical evidence and iterative writing assignments.

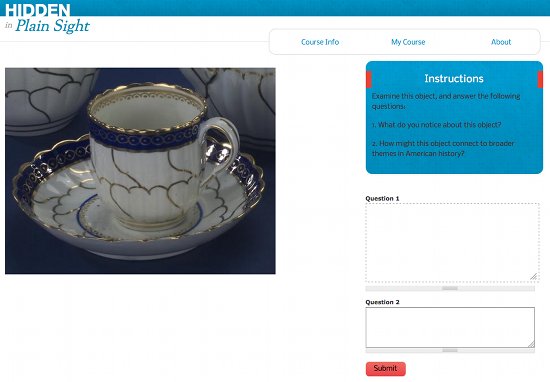

The course consists of modules, each of which begins with an everyday object.

Participants examine the object and hypothesize about its relationship to a larger historical narrative. After submitting the hypothesis, they learn about the broader historical context and significance by exploring selected primary and secondary sources. Finally, they reflect on and revise the initial hypothesis in light of what they have learned and create a classroom activity that integrates the content and methods.

The courses are developed using the open source content management system Drupal, allowing for flexibility and customization in building and administering the course. Based on teacher feedback and performance, we have revised the structure and curriculum to improve learning and provide more student control, including structuring the course so participants can move through modules in any order.

The upcoming posts in this series address two issues related to implementing and teaching these courses. One is the potential to rethink the timing of the traditional semester and the other focuses on making meaningful connections in online learning.

Celeste Tường Vy Sharpe is a Ph.D candidate in history and art history; Kelly Schrum is director of educational projects at the Center for History and New Media and associate professor in the Higher Education Program; and Nate Sleeter is a Ph.D. candidate in history. All are at at George Mason University.