You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

It is fair to say that MOOCs have captured the world’s imagination as to what might be possible for education, both now and in the future.

MOOCs have also generated controversy, with some wondering about their implications for residential education and others asserting that their hype exceeds their grasp.I would like in this blog post to address a slightly different question, which is what sort of learning can occur through MOOCs and other online offerings? We know that online learning works for knowledge and skills. But can MOOCs change the way people behave?

That was one of the questions that motivated the launch of the Harvard Graduate School of Education’s first-ever HarvardX MOOC. Entitled GSE1x Unlocking the Immunity to Change: A New Approach to Personal Improvement, the course was developed by Bob Kegan and Lisa Lahey, two of my faculty colleagues from the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) who are developmental psychologists and experts in adult development.

In this blog, the first of two, I’ll describe the way in which their course demonstrated that you can indeed change behavior, at scale, through a MOOC. In part two, I’ll talk further about the implications of this success, and why this course demonstrates that the conventional wisdom about the relationship between business and education is incomplete.

The traditionally delivered Immunity to Change course has become a core part of the training for school leaders at HGSE. It’s based on the belief that successful leaders need to be learners, and they also need the tools that will enable them to change habits and practices that are obstacles to their own success and the success of their institutions.

The basic idea behind the course is straightforward. It is widely known that the most significant and lasting improvements (in work performance or personal life) come about not through a focus on behavior change alone, but through a focus on changing beliefs and assumptions. For example, most diets focus on behavior change. People do lose weight, but for most it is only temporarily. Immunity to Change moves beyond this dieting model.

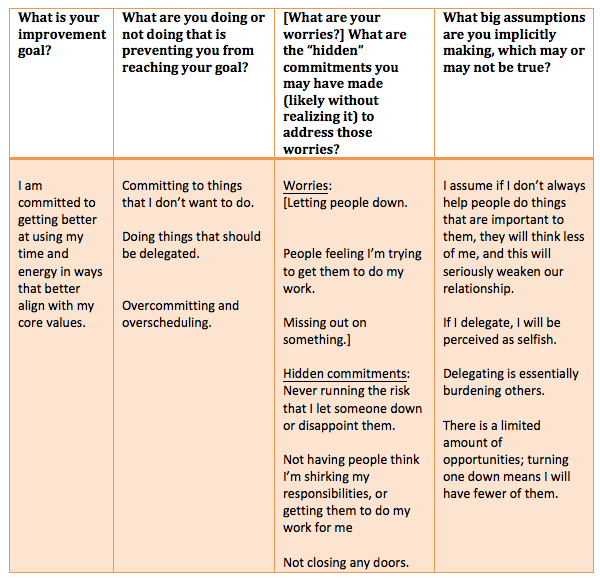

Here’s how. To begin, participants are asked to fill out an Immunity to Change map. The first two steps are to name an improvement goal and identify current behaviors that are preventing them from reaching this goal. Following this, students are asked to think about these behaviors and then express the worries they have about behaving in a different way. By identifying these worries, they are then able to identify a number of “hidden commitments” they may be harboring without fully realizing it. Finally, based on the previous steps, participants describe their related big assumptions—underlying core beliefs which may or may not be true—that have kept them true to their hidden commitments.

To illustrate, here is a brief example of what a filled out Immunity to Change map might look like:

Once they have completed their map, and have started to understand how their own “immune systems” are impeding their personal goals, students start to do the work to change. This includes exercises in conscious self-observation, consideration of how they would think and feel if released from their big assumptions, and then experimenting with different behaviors to give the world a chance to show them that their big assumptions might be invalid.

We know the conventional version of Immunity to Change has been successful in helping individuals and institutions make progress toward their improvement goals. It has worked in school districts and global financial services companies, and it has been recommended far and wide by those who have experienced it, including Oprah Winfrey. But the model always relied on an intensive coaching component, so it wasn’t clear if it could be brought to scale. Could Immunity to Change work for 25,000 teachers in a district? Or 100,000 employees in a multinational company?

The answer appears to be yes, as the online version of Unlocking the Immunity to Change has been a remarkable success. Over 80,000 participants from a total of 182 countries initially registered for the course. There has been significant attrition, as is common among almost all MOOCs when not accompanied by some external incentive to persist. But as the course reached its conclusion after 15 weeks, nearly 6,500 people were still engaged, which is roughly 100 times the number of students who can take the course each year on campus.

Those students, moreover, have reported the ability to make real and meaningful changes in their own lives, from becoming better decision-makers and managers; to becoming kinder and more compassionate; to identifying ways to manage anxiety, stress, or anger. Importantly, these changes have been confirmed by witnesses—participants in the course identified third parties who could testify, via surveys before and after the class, as to whether the participants actually changed their ways. Results are still preliminary, but 72 percent of the over 4,000 witnesses who have submitted their post-class surveys thus far have reported that their friends had achieved genuine improvement on their stated goals.

This is an important moment not simply for this course, but for online education. The early success of Unlocking the Immunity to Change suggests that online courses can be used not simply to impart information but to change behavior, and that participants in online courses can do this without one-on-one coaching from instructors. Indeed, one of the more remarkable observed aspects of Unlocking the Immunity to Change is how much the participants helped one another, which in turn suggests that peer-to-peer learning is an especially promising avenue for bringing high-touch courses to scale.

Based on the experiences of the past semester, we are now exploring the use of this learning technology to support at-scale professional and leadership development in both the public sector (for example, a large urban school district) and in private corporations (including a 100,000 employee company). We expect the impacts here to be even greater because there will be institutional norms, or tangible rewards for participation, which we expect will significantly reduce attrition.

The fact that this course is attractive and relevant to a private corporation leads to my second point, regarding the relationship between education and business. That is the subject of my next blog.

James E. Ryan is Dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Charles William Eliot Professor of Education.