You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

As Fair Use Week begins, Francesca Giannetti and David Hunter considers the use of readily and legally available digital media for MOOCs.

Their experience stems from assisting a University of Texas professor with an online jazz appreciation course.

In helping University of Texas at Austin professor Jeff Hellmer identify and include audio and video recordings as he set up his jazz appreciation course, first offered January 2014, Francesca Giannetti and I considered numerous streaming or downloading possibilities. To rely on fair use in the context of an open educational resource, where the course audiovisuals would be posted on YouTube, was untested legal ground. In our view Professor Hellmer’s uses were fair, such as 7-10 seconds of a song, embedded in a lecture, to illustrate a point.

But a potential problem existed inasmuch as a challenge by a content owner would require removal of specific material, which would ruin the lecture, unless the institution was ready to be sued or file a declaratory judgment action against the accuser. At that time we had not witnessed the example of Lawrence Lessig, who, when served in August 2013 with a take-down request by Liberation Music Pty Ltd., countered with a declaratory judgment request, and was successful. We knew that Sony BMG, for example, tolerates nothing as fair, even if we were to utilize DMCA Section 512’s provision to counterclaim fair use, with a full explanation. When the question becomes “is it worth engaging in a lawsuit to prove that 7 seconds of a song, used transformatively to illustrate a point is fair, or do we take down that audiovisual?”, most of us don’t enjoy the luxury of the resources to file the lawsuit.

During course development the MOOC platform’s technicians highlighted the audio and video that was available through YouTube, and agreed to make the links inactive after a relatively short period. Of course, the files were still available on YouTube itself after that time, so it remained possible for students to return to them directly.

This illustrates a balance of practicality and limitation of risk in the ever-changing and challenging environment of information provision of recorded sound and video. This provision remains the property of multi-national businesses that have very little interest in encouraging the educational use of their property, and even less in admitting that fair use principles apply to current modes of delivery.

In the music streaming group, we’ve got Spotify, Rhapsody, Deezer for our friends in Europe, Rdio, and Microsoft’s Xbox Music (and many, many others), Google’s Play Music All Access, and Apple’s iRadio. And don’t forget VEVO for music videos.

Rdio:

And YouTube:

In addition, there are a host of sites with user contributed content like Grooveshark and Soundcloud. These sites have terms of use that tell users not to upload content that infringes on the rights of IP holders, and they run the titles of tracks through a music database to check, but things slip by. Consequently, these sites frequently claim protection under the “safe harbor” provision of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, under which they are held unaccountable for copyrighted content until they are made aware of it. The Verge published an article on an interesting twist related to the safe harbor provision of the DMCA involving Grooveshark and pre-1972 recordings. Grooveshark is actually something of a hybrid in that it offers some licensed streams in addition to the user content.

In the user contributed content group, there’s Grooveshark:

And Soundcloud:

Lastly, there are radio services and curated sites like Pandora, This is My Jam, and Songza. These aren’t necessarily the best ones to go to for a known query though since they’re designed more to introduce you to things that you might like based on your initial input. You essentially select a playlist curated by other listeners, or by a MIR algorithm, and if you’re like me, the results can occasionally be irritating. Why, after selecting Baroque as the genre, Pandora thinks I want to listen to The Messiah in the middle of May is beyond me…

In summary, there are copious and growing amounts of (mostly) legal digital music to access on the internet these days, which makes the prospect of designing listening exercises for online music classes surprisingly straightforward. Granted, subscribers do not control the collection, so content could change or disappear from one moment to the next. But with a little searching, it can probably be had from one service or another. Of course, busy professors don’t really want to be messing with all these changes!

Embedding players in course-related material is also possible. Here’s a Spotify example, Louis Armstrong with the Hot Seven performing “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue.”

The Internet Archive also permits users to embed players. No user account is required to stream or download content, so the file begins to stream as soon as the user clicks the play button. Matching the exact album or recording requested by the professor gets a lot harder with this site, since most of the audio content is user contributed and no particular collection policy is being followed. This is a more modern recording of “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue” by Louis Armstrong & All His Stars that a user uploaded to the Community Audio section.

Returning to Spotify, here is Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five” from the album Time Out.

This is a slightly muddy MP3 of the same recording of Brubeck’s “Take Five” taken from the Internet Archive. Sound quality can occasionally be an issue in the Community Audio section, as these are non-commercial transfers, but the audio engineers who post their digital transfers of historic recordings tend to be very transparent about any noise reduction algorithms used.

UT’s contract with edX apparently stipulated that the course and all its materials must be completely free of charge. For this reason, creating a playlist in iTunesU for students to purchase is not an option. But embedding a player could be possible in assigned and supplemental materials, the things students will be consulting outside of the actual class episodes.

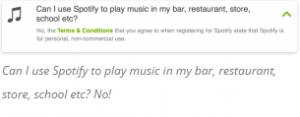

Spotify’s Terms and Conditions of Use make it clear that the service is designed for personal use only. This point is further clarified in their FAQ section:

As far as the school use goes, it is unclear if the primary objection concerns the use of Spotify as background music or if all institutional uses are similarly unauthorized. The TEACH Act might afford some legal protection for educational uses, but probably only for small portions of the work that are integral to the class session. Meanwhile, the terms of use agreement for the Spotify Play Button (i.e. the embeddable Spotify music player) is slightly different (and shorter) than their general Terms and Conditions. The language around individual users is downplayed here, probably because it doesn’t much matter. Whoever presses the play button must have an individual Spotify account in order for the music to play. Therefore the significance of the player’s location, be it on an institutional or personal website, seems low. Spotify still gets to preserve its individual end user model, and still gets to collect data on those individual uses. In a sense, UT the institution is acting much like Google, pointing the user to where the content is located, not reproducing it.

So at the very least, for the Spotify Play Button, we are looking at a kind of implied license, if not a crystalline example of fair use. If Spotify provided the functionality to allow users to embed players, it doesn’t make sense for the company to sue a segment of (institutional) users for embedding the players, since Spotify intended for that very thing to happen. What other purpose was the creation of embeddable players intended to serve?

This post, also available on the University of Texas Libraries Blog, is adapted from “A Forest of Streams,” and “Jazzed about MOOCs,” first posted by Francesca Giannetti on her blog “The Art of MOOCS” in May 2013. Francesca was interim Music Librarian at the University of Texas at Austin September 2013 to February 2014 before moving to be Digital Humanities Librarian at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ. David Hunter is Music Librarian, the University of Texas at Austin.