You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Numbers Don't Lie: 71 Stories to Help Us Understand the Modern World by Vaclav Smil

Numbers Don't Lie: 71 Stories to Help Us Understand the Modern World by Vaclav Smil

Published in May 2021

How useful are data without theory?

The answer depends on what you are trying to accomplish.

Vaclav Smil's latest book, Numbers Don't Lie: 71 Stories to Help Us Understand the Modern World, is a good argument for the benefits of atheoretical thinking.

The trends, levels, distributions, measures of central tendency and frequencies that Smil describes are not offered as evidence of a particular line of argument. Smil does not start with hypotheses of how the world works and then report data to confirm or disconfirm these statements.

Instead, the data (mostly) stand alone.

Reading Numbers Don't Lie is like spending quality time with a map. Data are the companion to geography. Both must be internalized first before one can figure which questions are worth asking.

Distressingly, Smil chooses not to include any data on postsecondary education. This lapse may be forgiven, as Smil provides quantitative insights on most every other part of the world.

For Vol. 2, I'd humbly ask Smil to consider a chapter on the key statistical indicators of global higher education change.

What data about academia might be interesting to surface?

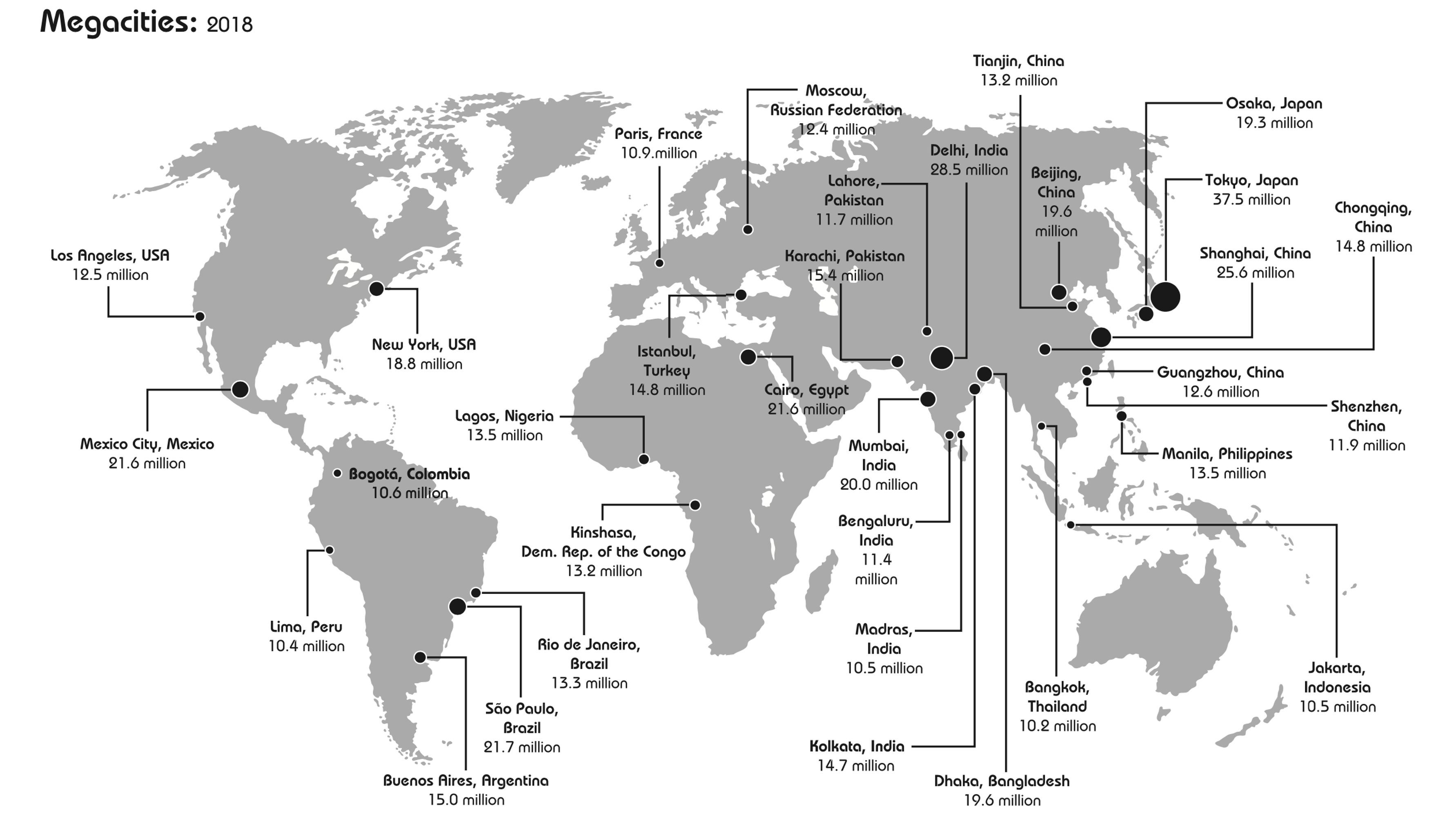

One of the most insightful chapters of Numbers Don't Lie is about the growth of megacities. A megacity is a city of over 10 million residents. Here is Smil's graphic of megacities in 2018, taken from the PDF that comes with the audiobook.

As you can see, only two of the world's 34 megacities are in the US. The urban population action is clearly in Asia. By 2030, six of the world's 41 megacities will be in Africa.

Will these cities be able to build campus-based universities quickly enough to keep up with demand?

The global higher education story is going to change dramatically in most of our lifetimes. By 2035, the center of postsecondary gravity will have shifted from cities and towns in the U.S. and Europe to megacities such as Delhi (43 million in 2035), Dhaka (31 million in 2035), Mumbai (27 million in 2035), Kinshasa (27 million in 2035), São Paulo (24 million in 2035), Lagos (24 million in 2035) and Karachi (23 million in 2035).

By all logic, the editorial offices of Inside Higher Ed should relocate from D.C. to Delhi.

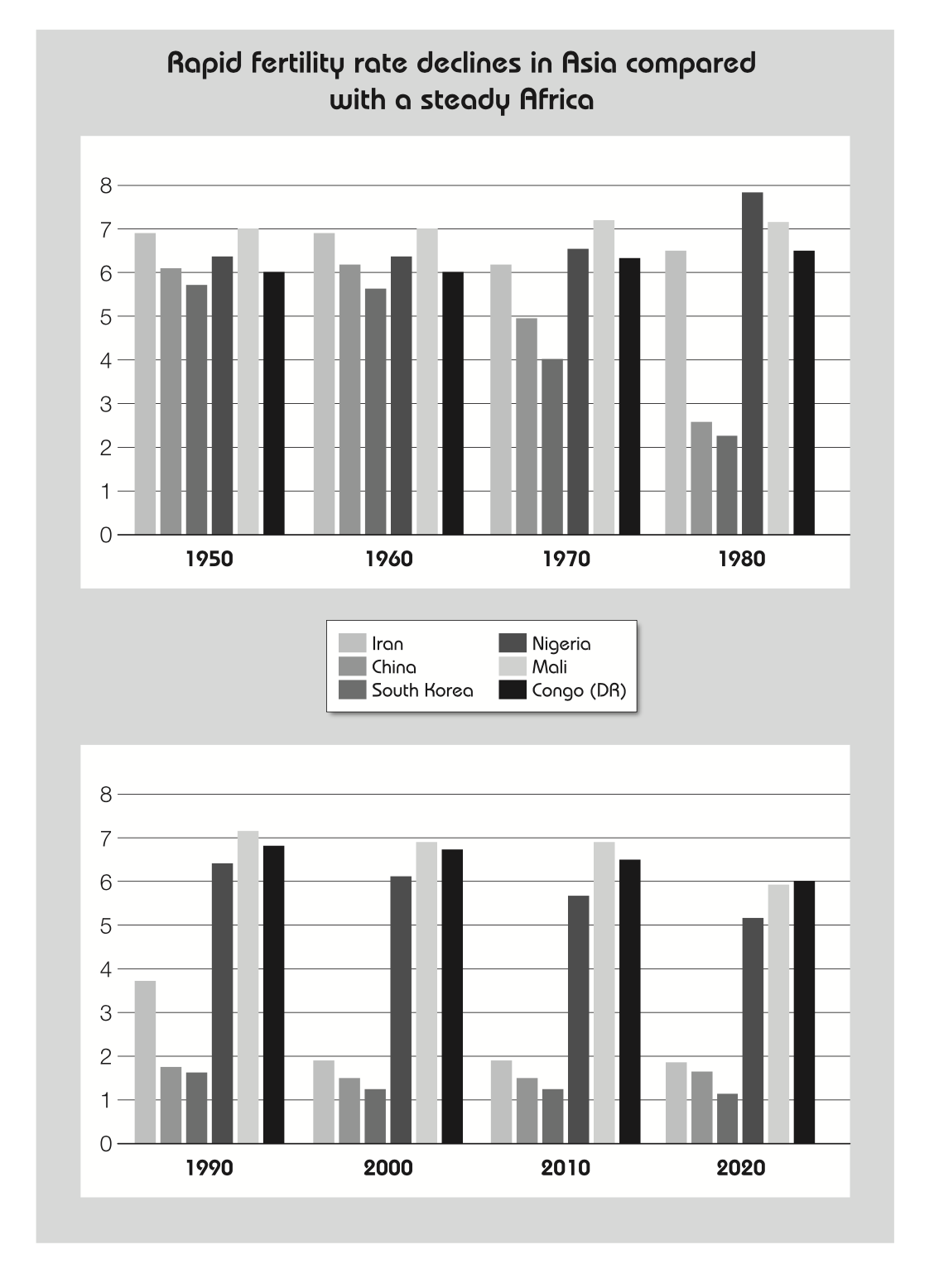

Another trend that Smil explores is the rapidly falling total fertility rate (TFR). (Again, see the figure from the book).

The TFR is the total number of babies that a woman can expect to have in her lifetime. Replacement fertility is a smidge over two, as both mom and dad need to be replaced.

Take a look at the path of South Korean fertility, from a high of near six babies per woman in 1950. Today, the South Korea TFR is barely over one.

In Korea, the result is empty university campuses and sparsely filled college classrooms.

Will the U.S. (TFR about 1.8) follow South Korea's path (and Spain and Italy and Greece and Japan and many others) and move towards a TFR of 1.3 and below? I have trouble seeing why not.

Our higher education system depends mainly on the existence of large enough cohorts of new high school graduates to fill our classrooms and residence halls. The number of high school graduates is already starting to plummet in the Northeast and parts of the Midwest.

If in the future should our nationwide TFR drop to South Korean levels, the demographic disruptions of the 2020s that so worry today's higher ed leaders will be remembered fondly as manageable blips.

Smil's Numbers Don't Lie makes for a helpful reminder that clear thinking requires some degree of quantification.

The book also equally reminds us that numbers can obscure as much as they illuminate without a set of theoretical frameworks to guide our thinking.

What are you reading?