You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Why haven’t digital technologies transformed higher education?

Should not the internet, the browser, the mobile device, and the app have fundamentally evolved how higher education is produced and consumed?

The answer to these questions might be found in the history of other game changing technologies and in other industries.

Tim Harford, whose book Fifty Inventions That Shaped the Modern Economy I’m currently reading, provides one possible answer in his article (taken from the book) Why Didn't Electricity Immediately Change Manufacturing?

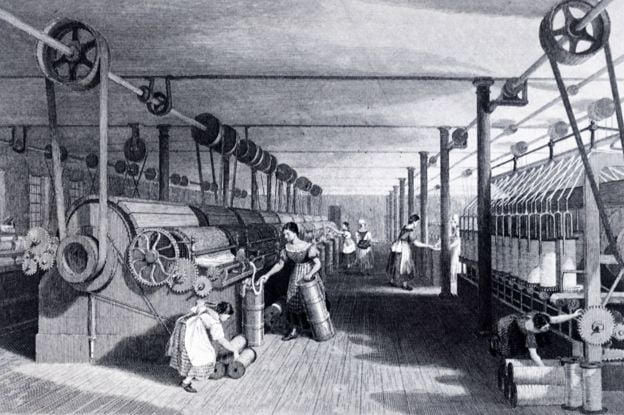

Harford points out that while Edison’s Pearl Station electrical plant was operational by 1881, less than 5 percent of factories were powered by electricity by 1900. The rest continued to be run by a steam engine powering a central drive shaft. All the machines in the factory were driven off this central drive shaft by a system of subsidiary shafts, all connected by belts and gears. The factories that did replace steam engines with electrical motors initially failed to improve their productivity.

It wasn’t until factory owners figured out how to fundamentally change the manufacturing process to take advantage of distributed electrical motors, rather than running all machines off a central driveshaft, that electrically powered factories took off. This shift from steam to electricity in the 1920s led to astounding improvements in industrial productivity.

The history of factory electrification in the early 20th century demonstrates that it is not the invention of new technologies that cause change to happen. Rather, it is the willingness of those using the old technologies to change their behaviors - sometimes dramatically so - to take advantage of the affordances that the new technology offers.

In the case of the transition from steam to electricity, this transformation took about 50 years. We might be in for a similar 50 year transition as we in higher ed figure out how to take advantage of all the affordances of digital technologies.

An interesting thought experiment to run is to ask if starting from scratch, would we design our colleges and universities the same way as they are now? Giving ourselves the freedom to think about redesigning our institutions from a clean slate may yield some interesting changes.

Given our shift in understanding of the critical role of active learning, would we continue to build tiered lectured halls with fixed seats?

How might we change the organization of our classrooms, labs, libraries, and residential facilities to encourage project based and experiential learning?

If we started from the premise of abundant information available on ubiquitous mobile screens, how might we design our physical environments to encourage collaboration and social learning?

In the decades to come I expect that we will experience a fundamental rebalancing between residential and online learning. Residential learning, I suspect, will get smaller and more intimate - personalized to the learner and increasingly structured around a relationship between the educator and the student. This high-resource version of face-to-face education will not be mediated by technology, but rather conform to a model that prioritizes interpersonal interactions, hands-on experiential learning, and coaching/mentorship by educators.

The cost of this method of non-scalable postsecondary education will continue to rise. I worry that this form of intimate residential learning (best seen at liberal arts institutions) will be increasingly restricted to the few and the wealthy.

On the other end of the postsecondary spectrum, I predict that more and more education will move towards large enrollment online courses supplemented by adaptive learning platforms. Learning and credentialing will move over the next decades from the browser to the mobile device to immersive virtual reality. Education that is primarily about workforce development and training, credentials that immediately qualify a graduate for a specific job, will be largely move to distance learning mediated by our evolving screens.

Our challenge in the next 50 years is to try to make sure that the relational model of education - one based on interactions between a well-qualified and compensated educator and a student - is not confined to only the most fortunate. We must find some way to leverage digital technologies to extend the benefits of a small-scale liberal arts education to more students than our current residential model can accommodate.

How do you think higher education will change in the next 50 years?

What lessons do you draw for the future of our colleges and universities from the history of the industrial transition from steam to electricity?