You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

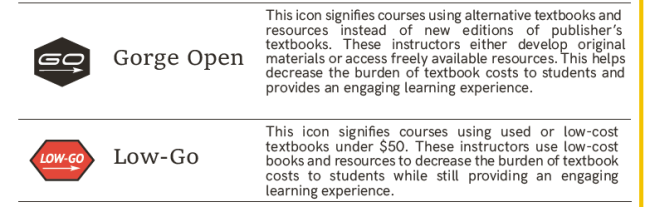

The courseware labels used at Columbia Gorge Community College

Courtesy of John Schoppert

Four states -- California, Oregon, Texas and Washington -- have in recent years passed legislation requiring institutions to add labels in course schedules and online registration systems for courses that use free textbooks or open educational resources (OER). Scattered institutions outside those four states have begun this process as well.

The recently or soon-to-be enacted laws differ in the strength of their requirements; Texas, for instance, established standards for private institutions as well as public ones, and California is requiring labels only for courses that use free content, without a specific requirement for highlighting OER. Proponents of such changes argue that more labeling promotes transparency and gives students with financial constraints easier access to courses that won’t require exorbitant textbook fees.

Some observers are more critical of the impulse to label courses, though, and implementation issues remain as the practice grows more widespread. Creating a labeling process requires contributions from multiple constituencies on campus, and some faculty members believe the system puts courses with required textbooks at an unfair disadvantage.

Organic Origins

According to Nicole Allen, director of open education for the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition, OER labeling is a natural outgrowth of existing price disclosure practices. In the mid-2000s, for instance, several states passed legislation requiring institutions to mark textbook costs in the course catalog. Now that that practice is fairly common, “it’s a natural extension to think about how [we can] improve the transparency of students in terms of what kinds of materials are in courses,” Allen said.

OER labeling allows students to make more informed decisions about the cost of their education, and offers transparency to students with limited financial means, Allen says.

Columbia Gorge Community College, in Oregon, was among the first institutions to begin labeling OER courses in registration materials, according to Allen. The idea for the change, according to John Schoppert, the institution’s director of library services, came from a 2014 open education conference at which one of the presenters put an OER icon on the conference program. Schoppert undertook the project, which took “a couple months,” with the institution’s bookstore manager.

“Students have told me coming into the library that they really appreciate that information being in the schedule,” Schoppert said.

Due to some technical challenges, the labels haven’t yet reached the online registration system, but they’re in the course catalog and on printed PDFs of registration offerings. Implementation into the online system is in the works, Schoppert said.

At Tidewater Community College, in Virginia -- another early adopter -- labeling became a part of the culture in 2013, at the same time the institution started offering its z-degree program and z-courses, in which students pay zero dollars for textbooks thanks to OER replacing 100 percent of the published course content.

“We don’t have to go in and guess which courses and which sections are z-courses,” said Linda Williams, professor of business administrator at Tidewater’s Chesapeake campus, and the institution’s faculty lead on the labeling project. Labeling also distinguishes student success data between z-courses and regular courses in the institution's back-end system, Williams said. As a result, comparisons are easier to make, and reveal that students in z-courses persist at a rate 6 percent higher than do students in traditional courses. Williams has also observed early evidence that students in z-courses take slightly more credits per semester -- possibly because they have money left over from their textbook savings.

Washington State, meanwhile, has undergone a trial-and-error process since its law was implemented in 2016, according to Boyoung Chae, policy associate for the state board’s elearning and open education department. The State Board for Community and Technical Colleges found that its initial "Open Educational Resources" label caused confusion among students and instructors, who didn't know what the phrase meant or how it was being applied, prompting a statewide survey later that year.

The survey helped the state board clarify the meaning of OER for those using the registration service. It also revealed a need for labeling other types of affordable materials that don’t fall under the OER banner, according to Chae. The state board distributed another survey this fall to gauge students’ “threshold of what is considered low cost for course materials,” Chae said. More than 6,000 students have already participated in the survey, which will conclude later this month.

Implementation Challenges

College bookstores typically manage textbook and course material adoption, which puts them in an important position as coordinator for OER labeling, according to Richard Hershman, vice president of government affairs at the National Association of College Stores. Stores typically solicit information from faculty members through submission forms to make distinctions on registration materials.

But the process isn’t always that clean, according to Hershman. For instance, label definitions can vary: Does the course require OER only, or a mix of OER and non-OER? Are the courses zero cost or simply affordable compared with typical textbook fees? What constitutes “affordable” and “low cost”?

Because registration typically opens half a year before the semester begins at most institutions, instructors sometimes change their mind about course materials in the intervening time. Publishers can change prices over that period as well. And in some cases, adjunct instructors aren’t assigned to courses until a few weeks before the semester, which means their courses might not have been accurately labeled up to that point.

The process can also be more time-consuming at quarter-based institutions, where version changes of textbooks and other materials need to be updated more frequently than at institutions with semester-based schedules.

The prospect of undertaking a massive labeling process can be intimidating for bookstores, Hershman said.

“They’re already heavily burdened. Some have cut back on staff, some have outsourced the course material delivery,” Hershman said. “Some of the resources, they don’t have as many as they had in the past. It’s a question of who’s going to assume that role.”

The association’s underlying concern, according to Hershman, is “making sure that whatever information [is] being provided to students is accurate.”

Jeff Seaman, co-director of the Babson Survey Research Group, which surveys faculty members about various technology issues, including the spread of OER, has already heard from faculty members who support these efforts. The one caveat he’s observed thus far, though, is that broad awareness of OER, among faculty members and administrators, isn’t yet widespread.

Some faculty members have reportedly expressed concern that OER labeling will put courses without OER materials at a disadvantage in the registration process. Williams, on the other hand, said this issue hasn’t come up on her campus. She thinks students' course decisions would factor in textbook costs just as much even without labels.

“Literally I have never heard a faculty member approach me or anyone on the team who felt like the fact that these OER courses existed in any way impacted in a negative way their enrollment in their courses,” Williams said.

Textbook publishers have largely stayed out of this debate, supporting transparency and acknowledging the concerns over the cost of materials, according to Marisa Bluestone, a spokesperson for the Association of American Publishers.

Observers agree that more course labeling is in the future, even as debates over proper implementation continue.

“Whether this happens through legislative mandates or campuses being transparent, I think we are likely to see more of this,” Allen said.