You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

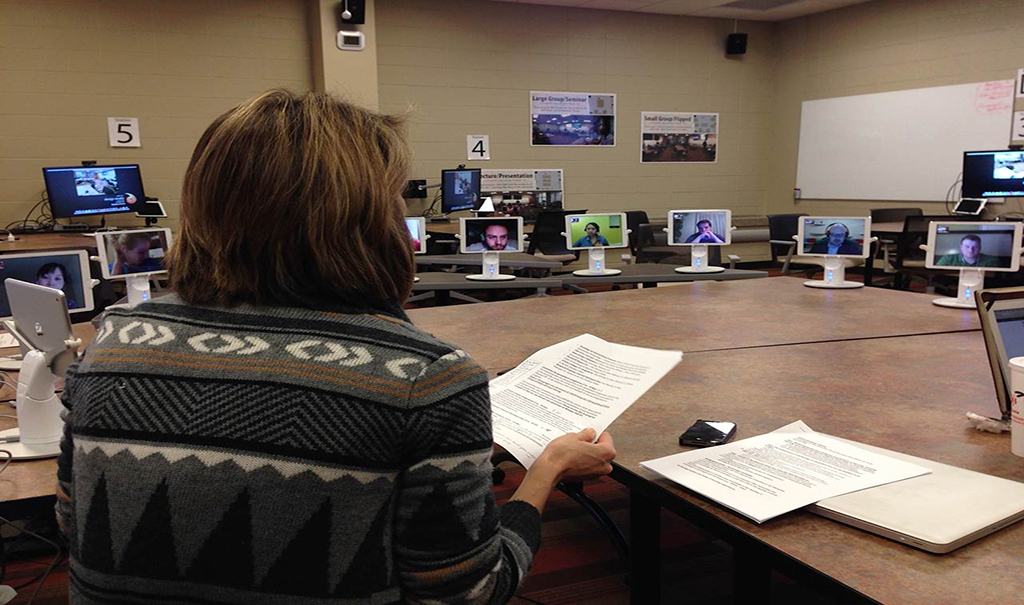

A face-to-face student sits in a class session with her peers at a distance.

Christine Greenhow/Michigan State University

Three years ago, Christine Greenhow, associate professor of educational psychology and educational technology at Michigan State University, attended a faculty meeting that would set her on an unexpected path. Presenters from the institution’s design studio showcased two different models of robots: a Kubi, which “looks sort of like an iPad on a neck that sits on a desk,” according to Greenhow, and a Double, which can roll around hallways.

The designers said they were employing the robots at alumni meet-up events, allowing out-of-town participants to mingle with their on-campus former peers. But Greenhow envisioned another place for the robots: in her own classroom.

Greenhow teaches doctoral courses with between 10 and 15 students -- some on campus, others participating synchronously online. For years, she struggled to bridge the “transactional distance” that remote students faced when trying to integrate into classroom discussions and activities. The robots, she thought, could solve that problem.

“If everybody felt embodied in a robot, I as the instructor would know exactly where to look. I’d look them right in the eye,” Greenhow said. “Also the ability to move -- in a videoconferencing environment, you take out a lot of these mobile cues, body language that shows attention. If both of these robots had the ability to move, maybe that would help us break down the distance that we feel.”

Greenhow has been using robots in her classes ever since. She recently published in Online Learning a study detailing her first attempt -- in spring 2015 -- integrating the devices into her classroom, revealing that online students felt more engaged when participating through the robots than when they appeared in the classroom via Zoom or another videoconference platform. The institution has since scaled up its robot inventory, purchasing 14 robots and using 15 more on loan.

“Any time you introduce a new technology, it’s fraught with anxiety. Inevitably problems happen,” Greenhow said. “Everybody has to be willing to take that risk.”

How It Works

To populate the robots, online students simply download free software on their personal computers and log in. They can remotely control their movements and zoom level using the arrow keys.

Greenhow says she was able to give more individual attention to students when she felt she could draw all of them into a conversation with equal success. On-campus students felt a greater sense of connection to their remote peers, she said. And online students reported feeling more engaged and less prone to distraction when using robots than when using the less advanced forms of synchronous online learning.

Robots don’t come cheap, of course. Each of the institution's 12 Kubis cost $600 per unit, not counting the cost of the iPad, sold separately. The Doubles, no longer for sale, cost $2,500 apiece and also require a separate iPad. All told, the institution has spent $10,000 on robots thus far.

Michigan State also acquired 15 Beams, with a wide screen and a tall body, on loan, but each one is valued between $2,140 and $13,950, depending on the model, plus an annual service fee of up to $500.

Students needed time to adjust to the possibilities and challenges of their new robot proxies, Greenhow said. Some students forgot to consistently turn their head screens to face the person who was talking. If two robots were sitting side by side, turning the head screen proved a challenge. Students in hotel rooms or other places without high-speed internet occasionally experienced connectivity issues.

The robots can also serve students with disabilities. A deaf student in one of Greenhow’s classes embodied a much-taller Beam robot (see sidebar), allowing him to zoom closer to people’s lips. Greenhow could see herself reflected in the student’s Beam screen, allowing her to monitor the effectiveness of her interpretation as she went. The student told Greenhow at the end of the semester that he preferred the robot to Zoom.

Greenhow adjusted her teaching style to accommodate the new technology. She tries to pause more often and reflect on how the technology is working, and to foster more dialogue among students. If distance students aren’t using the screen, she now takes time out of class to prompt them to do so.

The robots are an ideal fit for courses of her size and other small seminar-based courses, Greenhow said. Small student groups could also be well served by actively including online students in their efforts. Large lecture courses, on the other hand, would not lend themselves to a robot component, she said.

“Many of the large courses are straight lecture, where it’s less about an instructor talking [with] you -- it’s often about an instructor showing slides,” Greenhow said. “For that, the technology is not so good. You’d be better off to use Zoom.”

The study covered a class with a roughly equivalent number of face-to-face and online students. Greenhow thinks the robots are more effective in that situation, or even with a slightly larger imbalance, than when most students in the class are online.

How They Got There

Greenhow said she was nervous to get acquainted with the robots on her own -- but she had help from one of the institution’s “tech navigators,” who sat in on classroom sessions and performed on-the-spot troubleshooting.

John Bell, professor of educational technology and director of the institution’s Counseling, Educational Psychology and Special Education/College of Education Design Studio, oversees those tech navigators. His team purchased two robots for Michigan State on a whim after a previous project came in under budget. Early responses from students used words like “transformative,” convincing Bell that they merited further exploration.

John Bell, professor of educational technology and director of the institution’s Counseling, Educational Psychology and Special Education/College of Education Design Studio, oversees those tech navigators. His team purchased two robots for Michigan State on a whim after a previous project came in under budget. Early responses from students used words like “transformative,” convincing Bell that they merited further exploration.

In an early, pre-robot version of the experiment, Bell’s team mounted iPads onto classroom chairs occupied by face-to-face students, who would swivel the iPads for the online students when necessary. But sometimes a face-to-face student would turn to face another person but keep the chair in the same position, leaving the student on the iPad staring at a blank wall.

Bell wondered if students would consider the robots “too strange,” and indeed, some found them creepy on initial use. But enough students expressed enthusiasm that the experiment continued.

Empowering at a Distance

Online students get to preview the robots during the mandatory two-week intensive doctoral orientation. Bell’s assistant director meets with each one and shows them where their robot will be placed in the classroom and how it will move from place to place. Some students are initially concerned that they’ll be noisy or distracting when moving the robot; experience alleviates those fears, Bell said.

“That experience leads to the empathy of saying, ‘I know what it’s like to be on the other side of this, and I can better use it now in a way that’s respectful,’” Bell said.

Amy Chapman, a fourth-year doctoral student at Michigan State University, found out a week before Greenhow’s spring 2015 course started that she would be participating in the study -- but she was eager to get involved and satisfied with the result.

“Given that we’re in a college of education and learning about how people learn well using technology, it seemed like a logical fit. Most of the people in my cohort are kind of geeky.”

Though a broader cohort might yield different results, Chapman said she and her colleagues agreed that learning to use the robots was “pretty easy.” In fact, the main challenge for them was unlearning some of the hand signals they’d developed for coming to the class via Zoom. Once she learned “how to be a person again,” the robots were a natural extension.

“I felt like I’m not lost in the shuffle,” Chapman said. “Somebody is seeing me and so therefore I should put my voice out there.”

Next steps for Chapman include recording video of her classes and reviewing it to gain a better sense of how students interact with the robot technology. Bell’s team is working on a grant proposal for more robots but hasn’t yet decided whether to proceed with it, he said.

“It’s obvious that no single strategy is always the right one to use,” Bell said. “For us it always is, what is the current challenge in this class setting that we’re trying to resolve?”