You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Nine out of 10 start-ups fail, but when they do, founders and private investors -- not the state -- typically foot the bill.

That is among the reasons why this month’s closure of the University of Texas System’s Institute for Transformational Learning is drawing significant attention in Texas and elsewhere. It is quite rare for state leaders -- even in places like the Lone Star State, where going big is in the DNA -- to go all in on new technologies and emergent approaches as start-ups typically do.

Starting in 2011, the Texas system invested nearly $100 million in the institute ($23 million remains unspent) to try to drive digital technologies into the approaches its campuses use to reach, educate and graduate students. Over five years, the institute helped several UT campuses launch distinctive new academic programs and developed three core pieces of technology that, among other things, deliver online learning and students' transcript information via the blockchain. But its total revenue over the five years: $1 million, The Texas Tribune reported.

Critics have derided that output as paltry given the investment and questioned whether the money could have been better spent. Advocates for the institute say it was the sort of necessary and worthwhile experiment that higher education institutions undertake all too rarely, even as they acknowledge a set of miscalculations that -- along with political and cultural circumstances in part beyond its control -- contributed to its undoing.

Among those missteps, according to numerous people who worked closely with the institute, were a tendency to approach campus faculty members with arrogance rather than as partners, and a lack of clarity from the start about the endeavor's goals and business plan. Those were compounded by a problem that afflicts many educational technology efforts, whether funded by Silicon Valley investors or campus leaders: too little patience for what is almost always a long, drawn-out process of adoption and proof.

Understanding how and why Texas’ Institute for Transformational Learning failed -- and even some of its fans acknowledge its failure -- is important. Because whether the institute itself was a good idea, most colleges and universities will need to experiment, in ways big and small, to thrive going forward.

Born of Ambition

Like all too many failed start-ups, the Institute for Transformational Learning was born amid perhaps a wealth (and perhaps an excess) of ambition, bold words and loose money. In 2011, at the height of the frenzy over massive open online courses, the university's Board of Regents, encouraged by then chancellor Francisco G. Cigarroa, agreed to invest $50 million to "leapfrog" UT's existing efforts to use online and blended learning to educate more students more effectively.

The institute had lots of goals -- the standard tagline system officials used to describe said it would "expand access to educational programs, enhance learning, reduce costs and promote a culture of innovation" (yes, just those few things).

As it got off the ground in 2012, much of the institute's early work was focused on the flashy MOOCs, including a partnership with Massachusetts-based edX, and on building out technology platforms that could be used to launch the promised academic programs with UT campuses. In 2013 the organization hired as its chief innovation officer Marni Baker Stein, a national leader in digital learning with significant experience at Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania.

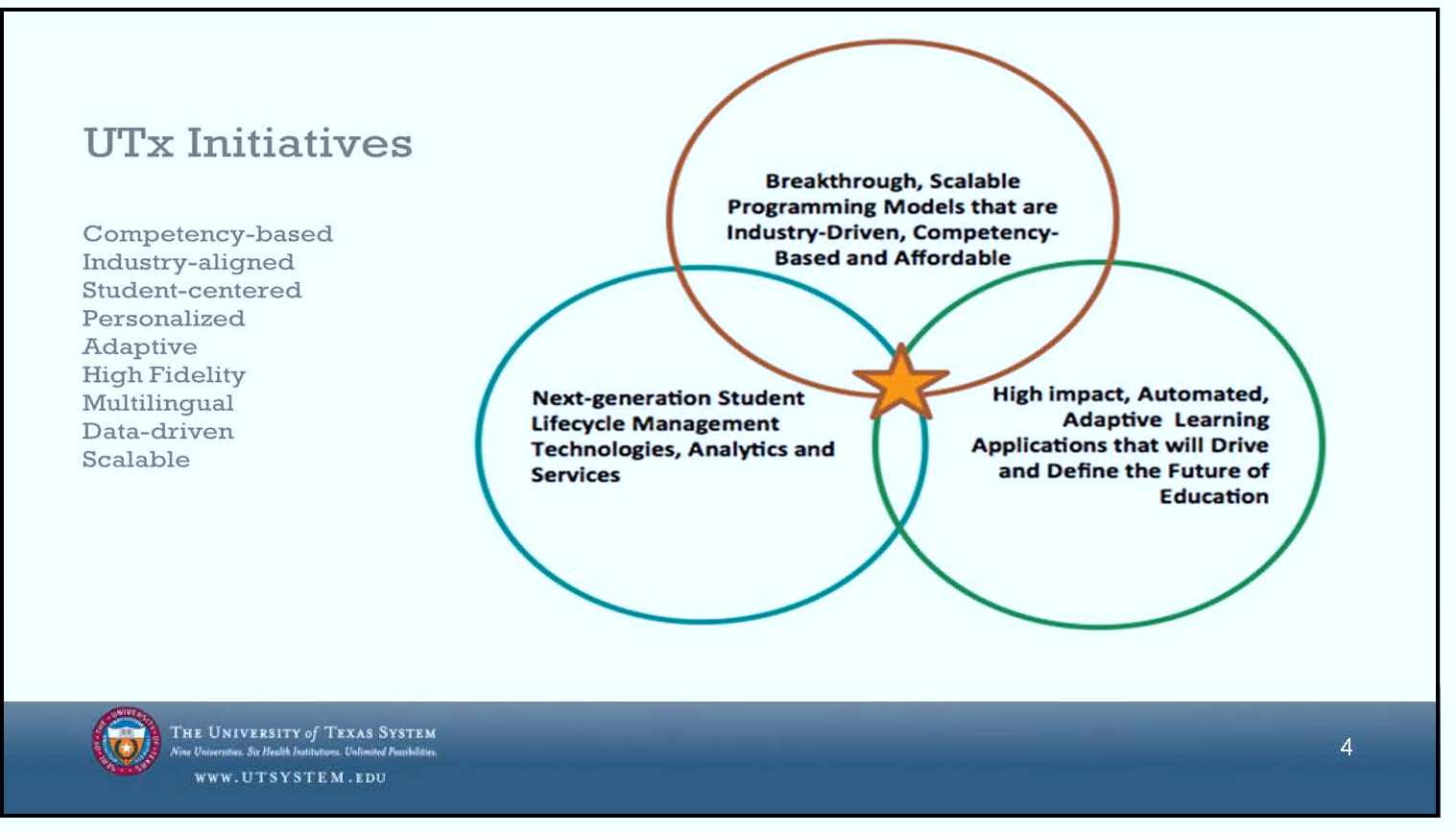

In the middle of 2014, Stein and Steven Mintz, the institute's founding director, made a set of statements to the Board of Regents that, if anything, raised the stakes on what it might deliver. In a presentation filled with promises (and buzzwords -- see slide below), they listed the Texas system's advantages to "compete and to win" in what Mintz called an "intensely competitive environment" and a "higher education landscape [that] is shifting under our feet."

Those advantages included 14 campuses "willing, even eager" to work together, an "energized faculty" that had embraced the role of instructional technology -- and of course the institute.

"ITL is poised to introduce a series of innovative programs, pedagogies and platforms that we believe will define the future of higher education," Mintz told the regents.

Mintz and Baker Stein's presentation did not include a word about the institute's finances, and the regents did not ask a single question about its spending.

And at the end of the meeting -- which happened to be the same one at which the regents chose Cigarroa's successor as chancellor, Admiral William H. McRaven -- the board doubled down, almost literally, allocating another $48 million in funding to the institute.

The Picture on the Ground

The institute worked on many initiatives, and many of them were significant: creating a clearinghouse for online courses throughout the UT System, developing a set of online gateway and rare-foreign-language courses, and coordinating the creation of a new curriculum for medical education at the system's health science centers, among numerous others.

One particularly intriguing effort was the plan to build a competency-based bachelor's degree in biomedical sciences at the university system's newest campus in the Rio Grande Valley, which emerged from the often-contentious merger of two institutions in the region.

The project was a particular priority for Chancellor Cigarroa; as a native of the region, and the first Hispanic leader of the UT System, he dedicated much of his tenure to improving the education and health of South Texas.

But the Rio Grande Valley experience laid bare many of the problems the institute experienced. The overall vision was for the institute to work collaboratively as a partner with faculty and staff members on the various campuses to build out the various initiatives, but the Rio Grande Valley campus was undergoing enormous turmoil related to the merger of two institutions, with some key professors leaving midstream.

"They were trying to open a new university, and questions of 'who's going, who's staying?' complicated what was already a really complicated process of trying to launch a whole new curriculum design and a whole new technological approach," said one person familiar with the institute's work, who requested anonymity. Among other things, training of faculty members -- a must for successful academic technology implementations -- got short shrift.

Because system officials wanted the competency-based program finished by the time of the new university's formal opening in late 2015, the process was rushed -- and that underscored another trait of the centralized institute: a tendency toward arrogance, say others familiar with its work.

"Any centralized service needs to be introduced by involving your partner organizations," said one person who worked closely with the institute. Because of the accelerated timeline on the Rio Grande Valley project, "they got too pushy with the faculty, who were already dealing with the merger, and it was 'here comes the system again to tell the campuses they don't know what they're doing.'"

While the new degree program did get launched in fall 2015, featuring the Total Educational Experience personalized learning app, the initial results of the experiment were unimpressive, and the Rio Grande program has stopped using the new platform.

The institute's subsequent major campus-based program -- a fully online cybersecurity bachelor's degree through the University of Texas at San Antonio's highly regarded cybersecurity program -- by all accounts went much more smoothly, in part because of lessons learned from South Texas. With a clear strategy, buy-in from a willing and eager faculty, and a better working relationship between the campus and the institute, the program has seen enrollments climb and appears on track to be financially viable.

New Players and Harder Questions

Whatever missteps officials at the Institute for Transformational Learning may have made in pursuing their strategy -- and even fans and former employees admit to mistakes -- ITL was also buffeted by factors swirling around it.

Its creator and original champion, Cigarroa, left his job as chancellor two years after it began work, and while his successor, McRaven, supported the institute, he directed its work to suit his own priorities, as is any chancellor's wont. Among the planks of his "Quantum Leaps" strategy to define the UT System's impact was an emphasis on national security, and the UT San Antonio cybersecurity program nicely furthered that priority.

But McRaven also encouraged the institute -- like many other parts of the system's operations he inherited -- to focus more on programs where they could clearly have success, rather than trying to "boil the ocean," as he liked to say.

Upon becoming chancellor in 2015, McRaven also "took a top-to-bottom look into the operations of ITL to ensure that the UT System was being a good steward of the funding that had been allocated," a system spokeswoman, Karen Adler, said via email. "Shortly thereafter, he called for the development of a business plan that included several benchmarks."

The pressure to assure financial sustainability of the institute (and control spending throughout the UT System) grew in the last 18 months, as a new crop of more frugal regents took increasing control of the board.

An April 2017 board meeting, where officials of the institute hoped the regents would approve an additional payment to Salesforce for their joint work on technology products, produced this exchange between one of those regents, Janiece Longoria, and McRaven.

“It appears that we spend a goodly sum on initiatives like this,” Longoria said.

“Let me assure you, we take the stewardship of these resources very seriously,” McRaven responded. He defended the institute and said it would generate revenue.

“I don’t disagree with that,” Longoria said. “But why has it taken over five years and we still don’t have a product?”

The Path From Here

Steve Leslie, the executive vice chancellor for academic affairs who oversaw the institute at the UT System and, with McRaven, decided to close it, said that decision was necessary because "there was a lack of a sufficient business plan from ITL to make it sustainable."

To some people who watched the institute's work along the way, that's not a surprise, because from the start the regents were unclear about what ITL's business model should be, and didn't demand one.

"It wasn't clear whether it was incubator or investment bank, whether it was there to help [campuses] or to make the money back," said one official who worked closely with the institute. "There was this idea that there was no charge [to the campuses] for now, but there might be later. I don't think any of that was ever made clear."

For this official and others, the need for clarity about goals and business models is one clear lesson from the UT System's experiment.

"Before you establish an organization, you have to be very clear about its goals," said this official. "It cannot be these broad fuzzy things, like 'drive innovation through change' or 'drive student success.'"

Centralized operations also need to get buy-in from their partners -- a central university department, for instance, needs acceptance from individual colleges or departments. "If you build something within a system, in this case, with the expectation that you can provide for the campuses and expect them to adopt what you've built, that doesn't work," said Leslie.

"It needs to be faculty driven, and it needs to be grassroots and bottom up," he added.

The kind of broad-scale change that the Institute for Transformational Learning tried to pull off may be difficult if not impossible, because "while it's really easy to pull one lever" to get incremental change, "when you try to pull a bunch of them -- all of them -- wow, that's hard," said one person who worked closely with the institute.

And if that kind of change is possible at all, it won't happen fast. "You have to play the long game, and the long game is really difficult for places like the UT System to invest in," said this official. "Not just because they are impatient, but because of all the changes that can happen in leadership and politically."

Some of the work done by the institute has been divested to the various UT campuses, and some of its products may be sold to other institutions or ed-tech companies. Its dozens of employees have scattered to companies like Blackboard and Salesforce and to other universities.

The institute's faithful say that its failure aside, higher education needs more experiments like it.

ITL was born at a time when "bricks-and-mortar higher education nationwide appeared to be at a precipice, threatened, on one side, by for-profits, and on the other side, by MOOCs and other online providers," said Mintz, its founding director. "While that existential crisis has abated, the underlying problems remain: challenged business models, inequities in institutional funding, unsustainable cost structures, distressingly low graduation rates at broad-access institutions, and uncertain learning and employment outcomes."

Colleges and universities "face a choice" in responding to those problems: "Play offense, play defense or stand on the sidelines," he said last week, in response to a critique of the institute on this site.

"Innovation is an iterative process, and I feel confident that the ITL vision -- with its emphasis on mastery, well-defined pathways undergirded by detailed knowledge mapping, personalization of pace and learning trajectory, interactive courseware with advanced simulations, bilingual content, and powerful social experiences, and a host of microcredentials aligned with the job market -- will have a long-term impact on the broad-access institutions that serve the bulk of the nation’s students."