You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

istockphoto.com/chombosan

Group work has long been a source of friction between students and instructors. At their worst, team projects force high-achieving students to compensate for those less willing to put in effort. At their best, they foster productive collaboration and idea sharing among future professionals.

Online courses add another layer of considerations for instructors. Students might be too far apart to meet in person, or too busy with other life commitments to schedule remote meetings. The impulse to lean on higher-achieving members of a group might be exacerbated by not having to face frustrated teammates in person.

“Group projects can be really great, and they can be a disaster,” said Vickie Cook, executive director of the Center for Teaching, Learning & Service at the University of Illinois at Springfield. “The most important thing is that they have a purpose. They’re very organized. Faculty and students have the same understanding of what the group project needs to accomplish and steps along the way to get there.”

Faced with these challenges, instructors have adapted old strategies and formulated new ones for group projects in online settings. Some instructors say implementing these strategies takes up more time than a comparable assignment in a face-to-face course; others aren’t as convinced of the extra workload.

Instructors who assign group projects to online students see their efforts not as a burden, but as a tool to help students learn and form relationships -- just as they might face-to-face.

Unique Challenges

Instructors say many of the fundamental characteristics of a successful group project online are consistent with what works face-to-face. There are some key differences, however.

At the Chicago School of Professional Psychology, instructors warn students about group projects at the beginning of the semester, rather than springing something unexpected on them.

“They’re online students; they typically have a lot going on in their lives, they’re full-time employees,” said Alisha DeWalt, associate campus dean. “We want it to be an efficient project that’s really driven to mastery of learning outcomes.”

Online students in marketing communication management at Florida Gulf Coast University have to present case studies as groups in order to critically analyze the kinds of content they’ll create in their careers. Ludmilla Wells, associate professor of marketing, has over the years worked hard to put constraints on sources she expects students to mine when preparing their projects.

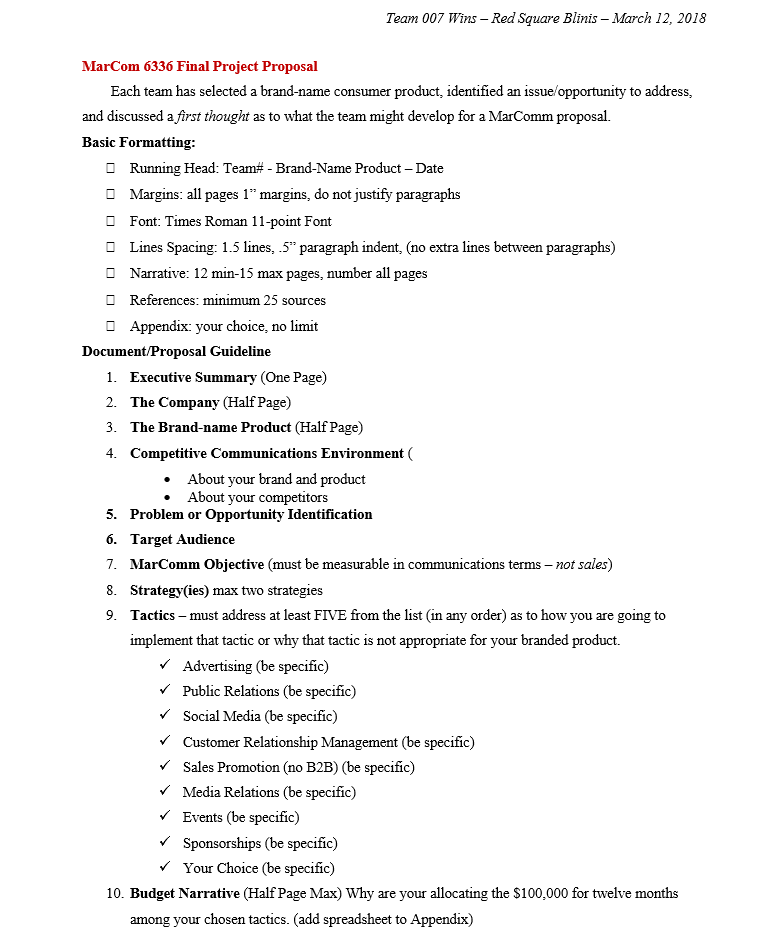

Because online students have the entire internet at their fingertips whenever their mind is on the course, they’re sometimes overwhelmed when searching for information. Wells provides students with “key points of entry” for information: magazines like AdAge and Business Week, aggregators like Smart Post and Media Brief. She also lays out specific expectations for the final product in writing (see image).

In person, instructors can allow students to work on group projects during class time, which gives them a window into how the students are doing. No such opportunities are available in an online class, which means instructors have to build in opportunities to see projects at various stages of completion, said Cook, who helps online instructors (and face-to-face ones) at Springfield strategize group project assignments.

Establishing learning objectives early goes a long way toward mitigating students’ frustrations with having to work in teams and concerns about collaborating with students they don't have access to in person, according to Cook.

“I don’t think any of us like busywork. Students especially don’t like group work because it’s difficult to schedule or because one group member pulls more weight, one group member pulls less weight,” Cook said. “Having that clarity of purpose puts you on a single field.”

Assigning Groups or Letting Them Form Organically

Forcing students to work together can introduce students to new perspectives and lead to healthy collaboration. It can also backfire if students don’t get along or their work styles aren’t compatible. Online, that dynamic can be heightened because students are operating with only a limited understanding of their fellow students' personalities and behaviors.

In her marketing courses at Florida Gulf Coast, Wells splits the difference. She lets students choose their team members for the case study project but assigns groups for discussion threads that take place throughout the semester.

Students in her course likely already know each other a bit from previous courses in the M.B.A. program. They’re also more likely to pick people with whom they share common interests or have compatible work schedules, Wells said.

That last point plays a major role in the success or failure of a group project in an online class. According to Cook, one professor at Springfield creates a communication plan with students -- posting everyone's detailed weekly schedules, swapping Skype IDs and cell phone numbers, establishing tasks for individual team members that will add up to a complete assignment.

On the other hand, dividing up the work too much can mean students aren’t really working together as groups, according to Darin Kapanjie, academic director of the online M.B.A. program at Temple University. It's easy for him to trace a disjointed final product back to an approach that minimized group interaction, he said.

Assigning groups can be a fraught exercise, though -- made more difficult by not meeting students in person. Steve Greenlaw, a professor of economics at the University of Mary Washington, likes to avoid grouping freshmen together because he wants new students to benefit from the wisdom of their older peers.

At first he tried to create groups with a mix of older and younger students, but he discovered that older adults found the younger students’ schedules and social media communication preferences untenable. Now he groups adults together, with the occasional exception.

“Sometimes when I have a group that is really struggling with the content or with getting in, I try to put an adult student who I know personally into that group to help stabilize things,” Greenlaw said. “That works pretty well.”

During group projects in his classes, Gregg Ramsay, professor of computer applications at Pace University, assigns one person in each group to serve as “project manager” -- a liaison between the group and the instructor, required to share twice per week an update on the group’s progress.

Ramsay’s students in groups are required to meet weekly on Blackboard Collaborate; if students miss the meeting, they can be “divorced” from the group and receive a failing grade for the project. Never in his 19 years of teaching online has this happened, Ramsay said. He believes online courses don't make group projects unfeasible -- quite the opposite.

“I've had a lot of success with them,” Ramsay said more generally of group projects in online courses. “I've never had any significant issues, and over the years I've been able to design the projects where the students take responsibility for completing their part of the project.”

Grading as a Whole or Individually

In key respects, instructors consider group projects in online courses no different from similar assignments in person.

Assigning a single grade to a group of students can mean rewarding underperforming students for letting their peers complete most of the work, or marking down students who tried their best for a project that didn’t come together.

IDL Tip

Several instructors interviewed for this story said they urge students to complete their group project work on Google Docs. Not only can students easily collaborate simultaneously on writing and research, but professors can easily look at the revision history to get a sense of whether students participated in equal amounts.

At the Chicago School, students do some of that work for the instructor, according to DeWalt. After finishing a project, students fill out a report on their own performance and that of their colleagues. Knowing they’ll be evaluated this way keeps online students engaged when they might be tempted to drift.

At Springfield, most faculty members in online courses give individual participation grades and a final group grade. Greenlaw, on the other hand, prefers for students to be responsible for the entire final product. Particularly in an introductory course, he doesn’t see the need to split hairs about how students acquired knowledge.

“Whether they figured it out on their own or whether they were taught by someone else in the group fundamentally doesn’t matter to me at this level,” Greenlaw said.

Why Do It At All?

Cook believes faculty members do spend more time constructing and executing group assignments than they would for more straightforward individual assignments. But students learn valuable skills in communication and group dynamics that will serve them well beyond the course. Their field of choice will likely require group work -- and it’s plausible that some of it might face logistical challenges like the ones presented in an online course.

Greenlaw thinks the workload is the same, and the workload is worthwhile for the same reason online as face-to-face.

“One of the things that I try to do is provide the same amount of interactivity in the teaching and learning online as I do face-to-face,” Greenlaw said. “I think that’s how learning happens best.”