You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

As it headed into the 2016 academic year, Excelsior College looked to be on a roll. Revenue from student enrollments and the exam services provided by the private nonprofit institution had risen by roughly $10 million in each of the previous two years, and its budget setters assumed similar growth from 2015 to 2016.

After all, demand for the one academic program overwhelmingly responsible for the budget increases -- the associate degree in nursing program, which accounted for nearly half of Excelsior's students -- showed no signs of fading amid a tight nursing job market.

But the college's leaders knew better: all was not well with the nursing program, which enrolled degree-seeking students who were already registered nurses or licensed practical nurses. Although enrollment of full-paying students continued to boom, topping out around 21,000 in 2016, their outcomes were increasingly a bust. Just one in six of the enrollees -- many of them minority women -- earned a degree.

"When you are enrolling people who are not going to be able to complete, you are setting them up for debt they can’t repay or spending money and getting no degree in return for that," James Baldwin, Excelsior's president since 2016, told a group of employees last month. (A two-hour recording of the conversation, for a time publicly available on an Excelsior webpage, offered an unusually honest glimpse into the college's internal conversations.)

With regulatory scrutiny of poorly performing for-profit colleges intensifying at the time, Excelsior officials felt what Baldwin called "a very significant vulnerability" in the associate nursing program. "They could easily have looked at the ADN program," Baldwin said in that April meeting. That program had also been the subject of litigation by unhappy former students.

In March 2016, the college's ailing president at the time, John Ebersole, and his fellow managers imposed a set of admissions requirements on a program that had previously admitted virtually all comers.

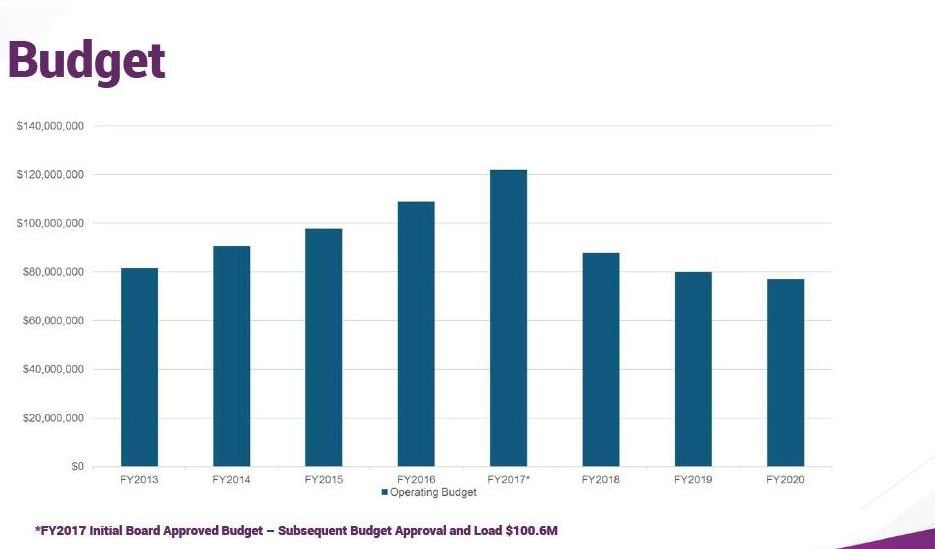

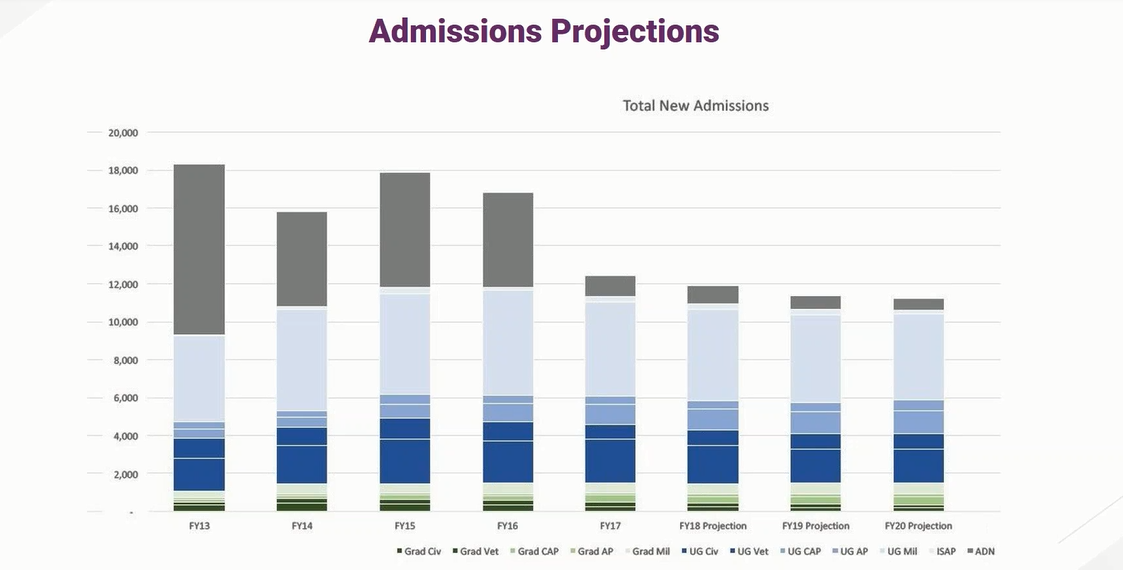

The impact was swift and painful: enrollment in the associate nursing program fell sharply (to roughly 10,000 now) and, with it, revenues -- the college's fiscal 2019 budget is roughly $80 million, about two-thirds of the 2016 projection. In the intervening two years, the college has slashed roughly 100 jobs and a third of its academic programs while abandoning several high-profile efforts aimed at broadening its revenue streams and reach.

Baldwin and the college's current leaders express faith in their plan to refocus on the institution's core mission of serving adult students with online and degree completion programs, driven by investments in improved technology and a national branding campaign. "Excelsior is one of the best-kept secrets in higher education," the president said in an interview last week, and with a market of many millions of American adults as potential students, "we are well positioned for the future."

Others, however, question the continued viability of a one-time pioneer at a time when other, bigger players (think Western Governors and Southern New Hampshire Universities) have moved into its space alongside surviving for-profit colleges and the handful of other state institutions that have long worked in the degree-completion realm. Confidence in Excelsior's executives (who have little higher education experience) has tumbled, and suspicion is high -- not surprising given rounds of layoffs and other cost-cutting, but a difficult climate in which to rally the troops.

History and Context

Excelsior was founded in 1971 by the New York Board of Regents (with funding from the Ford Foundation and Carnegie Corporation) to focus on adult learners, long before most colleges paid attention to those students. Operating as a state agency, first as Regents External Degree Program and then Regents College, it was among a small stable of nontraditional institutions (Thomas Edison State University, Charter Oak State College, Empire State College, the University of Maryland University College) that served primarily military service members, working adults and others. It became an independent nonprofit college in 1998 and changed its name to Excelsior in 2001. (Note: This paragraph has been updated from an earlier version to clarify Excelsior's early history.)

Excelsior and institutions like it have been both ahead of the curve and largely out of public view. Because the students they've served have not been the traditional 18- to 22-year-olds that most Americans (and most policy makers) pay attention to, they have quietly done their mission-driven work and, by most accounts, have been effective at it.

Excelsior’s primary visibility on the national landscape came through the Presidents’ Forum, a coalition of leading institutions in distance education for adults and other traditionally underserved students. The organization holds an annual meeting and other events designed to share good practices and strategies for online and other new forms of learning.

The forum was one of a series of initiatives that Ebersole, who became Excelsior’s president in 2006, put in place to try to raise the institution’s national profile and diversify its revenue base.

The college was heavily dependent on the associate degree in nursing, which focused on providing online content and prior learning assessment credit to practicing nurses who needed degrees.

Data shared by administrators in their series of presentations to employees last month showed that students in the program made up as many as half of all new students the college admitted annually in the early part of this decade (the top gray bars in the slide below). And because the nursing students were typically paying the full credit hour rate of $510 (unlike the many military students that Excelsior enrolls), they accounted for an even greater proportion of the college’s overall tuition revenue.

So perhaps it’s not surprising that even as evidence mounted that the program was underperforming, as evidenced by the filing of lawsuits by disgruntled students (one of which, in 2015, led to the settlement of a class action) and data showing that “only 12 to 16 percent of them were completing,” as Baldwin acknowledged in his April 4 presentation to Excelsior’s technology staff, the college’s leaders were slow to take action.

The March 2016 decision to impose admissions criteria (including the submission of a “proficient” score on the Test of Essential Academic Skills and a form verifying that applicants had prior health-care experience) probably came "about two to three years" later than it should have, Baldwin said in that talk.

“The data was there,” Baldwin told employees. “We knew there was a problem there, but there was a reluctance to lose the revenue.” (One wonders where the college’s accreditors were; officials at the Accrediting Commission for Education in Nursing did not respond to several messages seeking comment.)

The decision, when it ultimately came, "was based on the right values," Baldwin said. "To me, if an academic institution loses its integrity, then it’s time to close. Because if you have no integrity, you’re in a business that’s going to eventually expire."

Excelsior’s trustees approved a budget for the 2016-17 fiscal year that envisioned generating $122 million in revenue, much of it from the nursing program, as seen in the slide below. But when Baldwin assumed the presidency that May, after Ebersole took a leave amid his cancer fight, the college lowered its estimate to $100.6 million, a spokesman said. (Ebersole died in November 2016.)

The nearly two years since then have been very difficult for Excelsior. Enrollments and revenues have indeed fallen sharply, and the college has eliminated roughly 100 jobs through layoffs and attrition. About 60 of those cuts came just last week, as the college headed into the 2019 fiscal year with what Baldwin described as an $8 million gap on a budget of roughly $80 million.

Employees who were willing to speak up at last month's staff briefing described poor office morale, "poor leadership practices" and the difficulty of working for a long period of time under a "scarcity mind-set," in which constant talk of budget cuts dominates day-to-day operations.

Many said they were reluctant to speak up, though, because "they feel it puts a target on themselves," said one senior staff member. "Due to the instability of the college, the budget cuts, the elimination of positions," they feel "if they do come forward, their position will be vulnerable."

The Outlook

Baldwin and other senior administrators sought to reassure employees both that they should not fear retaliation and about Excelsior's viability going forward.

They asserted that the college is about two-thirds of the way through a "three-to-four-year repositioning" that involved shedding (they prefer the term "rightsizing") unnecessary and unprofitable operations (including virtually all of the initiatives that Ebersole started to try to diversify Excelsior's revenues away from the nursing program). The college will move from five schools to three and from about 160 degrees and concentrations to under 100. A study done for the college by Gray Associates found that 78 percent of its students were in 15 percent of its programs.

It's not all about cutting, though: the college is investing heavily in new technology -- new financial software is to be unveiled in July, and a new student information system is scheduled shortly thereafter -- and Baldwin says the college knows it needs to invest more in marketing to compete for the adult students on which it has long focused.

"We've essentially refocused on our core as a completion college, an institution that has served adult learners with degree completion and other opportunities that are available in other higher education settings," Baldwin said in the interview last week. He said the college had a "stable book of business" in the $70 million to $80 million range.

But the world is a very different place from the one in which Excelsior has long operated. While it remains somewhat distinctive in the extent to which it uses prior learning assessment and awards significant academic credit to students toward completing their degrees, many more colleges are focused on serving adult students than was previously the case, and the number of colleges operating high-quality online programs for working people is escalating.

Scores of public and private nonprofit colleges now offer adult degree-completion programs (see this Google search as evidence) and the cost of competing in that realm is soaring.

"They're focusing, or refocusing, on adults and degree completion at a time when a huge group of institutions, public and private, are coming into that area," said Dennis Devery, vice president for planning and research at New Jersey's Thomas Edison State University, which has much in common with Excelsior as an online institution focused on adult degree completion.

While Devery said that institutions like his and Excelsior should have some advantage over the newcomers because they've been focused on those students for a long time and have generous and well-understood transfer policies, the strong brands and/or large marketing budgets of the new players make the current market a much more difficult one.

"It's as competitive as it's ever been," he said.

Pam Tate, president and CEO of the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning and an Excelsior trustee, acknowledged that the college will "never have the kind of marketing dollars" that big players like the University of Phoenix, Western Governors and Southern New Hampshire have (though she noted that the college has "significant reserves" that it can use to invest in new initiatives).

But after "what has been a rocky road the last two years," she said she is heartened by the changes Excelsior has gone through. "I feel like they've had to endure the pain to get repositioned for the future in a positive way. Excelsior is going to continue to be a competitor."