You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Istockphoto.com/ImagePixel

Mary Niemiec, associate vice president for distance education at the University of Nebraska, hears all the time from faculty members and others who believe online courses must cost less to produce than face-to-face classes because they can be left untouched after launch. She wants everyone who still believes that to understand why they’re wrong.

“That’s like telling a faculty member, once you develop a syllabus, don’t worry about updating it,” Niemiec said.

At the risk of a tortured analogy, maintaining online courses is like raising children: they need consistent care and attention, and plenty of grooming and upgrading as they mature. Within a few years, depending on the complexity of the course and the capacity of the institution, the cost of those efforts can outstrip the original launch cost. (To be clear, in this article we're talking about the cost of producing a course, as opposed to the price charged to take it.) Online program administrators and observers believe those investments are just as essential as the initial one -- but they don’t often come up in conversations about the cost of online production.

Some institutions have established concrete formulas for gauging ahead of time the likely cost of a mature online course, while others make adjustments as they go. Awareness that online courses aren’t self-sustaining is growing, though a precise, widely applicable formula for creating high-quality and financially viable programs over the long term has yet to emerge.

First, a blanket caveat: each online course is different from the next. Officials interviewed for this article hesitated to offer broad statements about these issues, emphasizing the diversity of needs and approaches to dealing with mature courses. Their comments paint a diverse picture of the online landscape that suggests success can come from many different tactics.

What Needs to Be Changed

Institutions are still catching on to the need for engaging with online courses at many points in their life cycle, according to Paxton Riter, CEO of iDesign, a Texas-based company that offers instructional design support to institutions as they develop online programs.

“Just like there are a handful of universities that do online education really well, there are probably a handful of universities that do quality assurance/continuous improvement really well,” Riter said. “It’s not anybody’s fault. [Instructional designers] feel like they’ve been screaming this from the mountaintop for the last two or three decades, but now it’s top of mind for everybody.”

Particularly given that many online courses are created under time duress or a broad institutional mandate, perfection is difficult to achieve out of the gate.

Many early efforts to bring face-to-face courses online involved merely recording lectures and uploading them to a learning management system. As the possibilities of online become increasingly diverse, updating a bare-bones framework is a no-brainer.

But not all update and refinement needs are so clear-cut. Content in some courses in subjects like political science and information technology quickly becomes outdated as current events inform elements of the discipline or even expand its boundaries. Rapid advancements in digital technology can render previously viable media elements clunky or defunct. Errors in spelling, minor facts and hyperlinks can jolt a student out of progress in the course.

Yet another layer of updates can come with a sophisticated understanding of data that’s assembled from early iterations of the course: which exercises and projects students prefer; how student outcomes compare in one section compared with another; whether the course’s layout meets the learning objectives and makes full use of the online format.

Efforts to tap in to this wealth of statistical information are increasingly common, as with Ohio State University’s distance education office, which launched five years ago with the goal of systematizing review processes for the institution’s then-burgeoning foray into digital learning, according to Robert Griffiths, associate vice president of distance education.

Griffiths's team checks in with instructors periodically during the first semester of their new online course. A more formal update process happens after the first semester, and the institution revisits the course for a substantial refresh after it's been taught for two and a half years. The digital learning office also provides professional development webinars and workshops throughout the school year, Griffiths said.

“I think sometimes in the in-person course, you have a sense of the room, what people are resonating with, what people are reacting to, but perhaps by the end of the semester you don’t quite remember,” Griffiths said. “Data gives a pathway to finding what would most effectively improve the learning experience.”

Imperatives to tweak courses can also come from outside the institution. State licensure and accreditation requirements, as well as accessibility standards, periodically reshape expectations for online program content. Institutions that brand themselves as work force-savvy, including Western Governors University and Walden University, also consult employers in relevant fields when determining whether online classes need a refresh.

It’s possible to do work as a course is being launched to minimize the number of changes needed in the short term. At New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering, the online learning team led by Jessie Guy-Ryan works closely with instructors before a course is launched to help them steer clear of mistakes that can cause headaches down the road, like videos that mention specific calendar due dates or rapidly evolving technology tools.

The institution is also hoping to start including more perspectives from students and alumni into the design process for new courses, in an effort to avoid obvious pitfalls that students have previously encountered.

How Institutions Make Changes

Institutions with large online portfolios have implemented review processes that put online courses under a microscope every couple years, or in some cases even more frequently. Faculty members and instructional designers team up to fix bugs, improve deficiencies and account for changes in technology, content and pedagogy.

The University of Nebraska “factors in a three-year life cycle” for its online courses, though it makes smaller upgrades even more frequently, according to Niemiec. But each three-year mark prompts a “really good look at this course to make certain the curriculum and technologies we can use are up-to-date,” Niemiec said.

At Walden University, the maximum period for an online course without a major refresh (or "academic program review") is five years, but some courses get updated far more frequently, according to Ward Ulmer, the for-profit institution’s interim president.

Each online course has a designated lead faculty member who monitors all sections of that course for broken links and minor maintenance issues. Once a year, the lead faculty member assembles a learning outcomes report -- known at Walden as the “LOR book" -- which examines whether students are meeting outcome goals and proposes strategies for improving engagement. (Here’s a sample.)

“It’s a faculty-driven process. These are the folks in the trenches,” Ulmer said. “They’re the first ones to come across, if we’ve got [a dead link], we want them to find it before the student finds it.”

Each program also goes through a multiyear academic program review cycle. “That’s when we really go in and do a remodeling of the course to make a refresh of that course, to make sure after all these pieces of data we’ve looked at, we make sure we’re not just putting Band-Aids on things that need to be rebuilt,” Ulmer said.

That review loops in the lead faculty member, a subject matter expert from within or outside the institution, and a Walden “academic champion,” who ensures the course continues to fit within the broader program.

NYU’s engineering school returns to online courses two years after launch, with possible updates including redesigning assignments, creating additional scaffolding, facilitating peer engagement and transforming project assignments. The institution has gradually made this process more rigorous, Guy-Ryan said.

“What we’ve learned through experience is we want to have these purposeful checkpoints; we want to allocate these resources and have this revisions,” Guy said. “It was really about putting a structure on that time.”

More From "Inside Digital Learning"

A recent study offers insight into the return on investment for online programs.

Debate over cost of online production continues to polarize.

A performing arts college thinks it's found a formula for efficient online growth that benefits students.

The online program management provider 2U accommodates its partners multiple times each year, at the start of each new student cycle, to revise assignments and assessments. Sometimes the company’s 12-person course iteration team will urge an institution to scrap an online course and create a new one from scratch.

That team is led by Tina Keswani, whose background is in television, film and video production. Andrew Hermalyn of 2U says the company considers Keswani’s team “strategists who are thinking about ways to reimagine the classroom environment online.”

Institutional partners tend to ask about course iteration in the earliest stages of a potential partnership with 2U, Hermalyn said.

“Because it starts in some of the early conversations and continues through, it’s a constant ongoing discussion, and we’ve never really had a case where we have not had a university partner say, ‘We need assistance here, we need guidance here.’”

Western Governors University employs a team of more than 200 faculty members dedicated to curriculum program development. That team follows the life cycle of an online course with a focus on learning outcomes, design and learning resources. Course updates happen each year on a rolling basis.

The institution recruits for that team terminal-degree faculty members with a focus on curriculum development, as well as instructional designers and assessment developers. The latter, according to Western Governors president Scott Pulsipher, “is becoming an increasingly demanded expertise because of the advancement of online or distance education programs.”

“The rapid emergence of online programs and courses has really tested the skill sets of faculty to do this not only in an effective and high-quality way but also in an economic way,” Pulsipher said.

Enrollment at Western Governors has been growing at a rate between 15 and 20 percent per year, while investment in information technology infrastructure increases by 10 to 12 percent each year. “It is an area where we have operating leverage,” Pulsipher said.

How Much Changes Cost

Ann Taylor, assistant dean for digital learning at Pennsylvania State University’s College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, last year conducted an in-depth analysis of her institution’s online course maintenance practices after an online program struggled for a few years to secure enrollment and "debt got out of hand." She hit on an analogy that summarizes her assessment of the cost landscape: “Asking ‘How much does it cost to offer a mature online course?’ is like asking a friend, ‘How much will the annual expenses be for my new car?’” Taylor wrote. “Before your friend can answer, she will need a lot more information.”

Her college has since developed an intricate system of categorizing and quantifying efforts on a number of tasks related to online course maintenance. Learning designers record the amount of time they spend on particular courses each month, leaving administrators with a detailed picture of how much maintenance each course required.

Not every institution has the capacity for such variability in cost, though. Western Governors University has determined a slightly more precise formula: for every dollar invested to launch an online course, the institution will spend between 25 and 35 cents in each of the subsequent three years. Pulsipher said the institution has become fairly adept at predicting where a particular program will fall on that spectrum, though its guesses aren’t foolproof.

Further Reading for Deeper Context

Change magazine in 2010 published a guide to reducing costs and improving effectiveness of online programs.

The Journal for Online Learning and Teaching in 2014 published an overview of the potential fruits of instructional design collaboration.

The National Center for Academic Transformation in 2014 published practices for redesigning college courses, including online courses.

Most recently, a new program in integrated health-care management ended up requiring closer to 50 cents per dollar in maintenance each year. Enough programs end up requiring less maintenance than average that these anomalies don’t prove debilitating, Pulsipher said.

The University of Florida, on the other hand, at one point invested only a fraction of an online course's launch cost in annual updates. According to its 2013-19 strategic planning document, the institution spends an average of $52,300 per online course at launch, followed by $7,500 each year for updates. Evie Cummings, assistant provost at the university and director of University of Florida Online, told "Inside Digital Learning" that the actual cost of updating online courses varies significantly. Updates are scheduled for every three years but instructors can request them more frequently, Cummings said.

Some institutions interviewed for this article were more reticent when pressed to compare the cost of launching and maintaining online courses. In most cases, they said course costs range so widely that any direct comparison would be misleading.

Looking more broadly, the majority of costs for online program maintenance go toward instructional design, according to Howard Lurie, principal analyst of continuing and online education at the research firm Eduventures. Lurie points out that a recent survey of chief online learning officers at U.S. institutions found that only 31 percent of responding schools report employing instructional designers.

“What that might suggest is there may be not a lot of long-term investment being put into initial design of courses and long-term iterative improvement with data,” Lurie said. High-quality courses can also breed student persistence and positive brand awareness, he said.

Some factors out of an institution’s control play a role in cost as well. Turnover among administrators or faculty members involved in online course development can lead to longer and more costly processes for keeping courses in shape, according to Vickie Cook, executive director of the Center for Online Learning, Research and Service at the University of Illinois at Springfield. Increasingly sophisticated cybersecurity infrastructure can also drive up costs for online courses as they grow, Cook said.

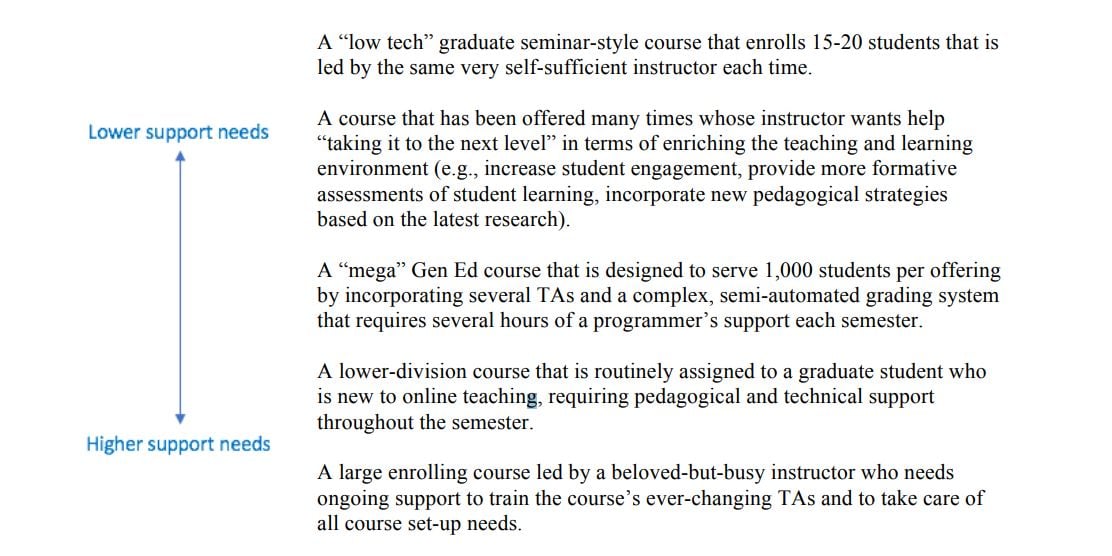

Courses fueled by a strong instructor presence can be more costly, particularly if they allow for high enrollment, Niemiec said.

A course refresh in NYU’s engineering school, including staff time, can cost half the full development cost. According to Guy-Ryan, those costs eventually pay off in quality.

“I definitely would caution any institution from thinking of these as a quick moneymaker, at least if you want to do it right,” Guy-Ryan said.