You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

istock.com/AntonioGuillem

When classes resume at the University of Kentucky next week, the world will look very different for the university's undergraduates. Some of them will be studying at home, virtually. Those who've chosen to live on campus will take a mix of in-person, hybrid and online courses, the former in physically distanced classrooms wearing masks under the shadow of COVID-19.

Very little about the fall will be "normal" -- except for how students are graded.

"The unprecedented disruption of normal academic operations during Spring 2020 required extraordinary departure from existing grading policies (e.g., broader allowance of pass/fail grading). For fall 2020, the university will return to its ordinary grading policies," the university says in an FAQ on its website.

The University of Virginia is taking a similar approach. So is Carleton College in Minnesota. And the City University of New York System.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is among numerous institutions going a different direction. Yes, letter grades will return, but "there will be no possibility of failing a subject -- that is, for performance at the level of F, instructors will report a grade of F/NE, and no record of the class will appear on the external transcript," MIT officials explained last month. A student who gets a D can accept the grade or keep the grade off her transcript.

Those and other "safety nets" are needed, wrote Rick L. Danheiser, the A. C. Cope Professor and Chair of the MIT Faculty, to "ameliorate the effects of the significant disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on students and instructors."

Fall 2020 will be a semester like no other. It will be different from last spring's chaos of a mid-semester pivot from on-campus instruction to emergency remote learning, which upended student and faculty lives and led many institutions to embrace a wide array of more-flexible policies related to grading, assignments and other academic matters.

But whether colleges are continuing with virtual learning, bringing some students back to campus for in-person instruction, or something in between, the student and faculty experience this fall is likely to be filled with a mix of uncertainty, upheaval and health worries, as it was in the spring.

Most instructors who are teaching hybrid courses, teaching to students in person and online concurrently, will be doing so for the first time. Students living on campus will be in a greatly transformed landscape, wearing masks, restricted in their social activities and perhaps worried whether students six feet away are carrying the coronavirus. Those learning from home, meanwhile, still may not have quiet places to study or consistent internet.

Or, as a report released Tuesday by the National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment puts it: "We are in a pandemic. Still. Do not forget that it is also an inequitable pandemic."

The report examines the results of a survey of hundreds of college instructors and assessment professionals about how they approached grading, assignments and other academic matters last spring. It finds that most instructors and institutions altered their approach to student academic work, from altering assignments and assessments (away from high-stakes exams, for instance), being more flexible with deadlines and embracing pass/fail or other modified grading.

Most respondents believed those changes were appropriate, helpful shifts to respond to unprecedented student needs, and that the downsides were few. Those who were troubled were worried about undermining the culture of assessment on their campuses and having "accurate representation of learning" from the spring. Various colleges' moves to pass/fail and other more permissive forms of grading in the spring were controversial at some highly selective institutions, where students caught on a hamster wheel of pressure around scholarships, graduate school applications and competitive internships feared it would put them at a disadvantage.

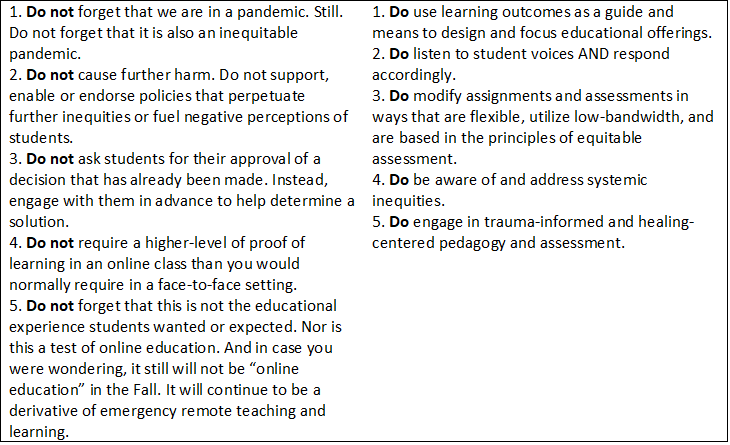

The survey's findings are worth reading. But the report's most valuable contribution, as I read it, is the list of "do's" and "don'ts" it offers for what's ahead. (See box at right.)

The survey's findings are worth reading. But the report's most valuable contribution, as I read it, is the list of "do's" and "don'ts" it offers for what's ahead. (See box at right.)

The fundamental reality underlying the report's recommendations is that as much as college administrators, faculty members and students may wish it were so, the teaching and learning environment (like just about everything else about collective lives) won't be anything resembling normal this fall.

Colleges and universities are doing everything they can to improve the experience, says the report's author, Natasha Jankowski, NILOA's executive director and research associate professor in the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign's department of education policy, organization and leadership.

They'll have made a difference: more professional development for faculty members in building and teaching effective, engaging online courses or in shaping hybrid classes; improved software and hardware to help deliver those courses and help close the digital divide for students without adequate technology; and more.

"We're shining a spotlight on particular things we can control, and we're going to try our best," Jankowski says.

"But regardless of modality, it's going to be rough. Some institutions have paid attention to the wrong things, and are now having to scramble. We have overstressed the faculty, throwing professional development at them all summer and knowing they're going to have to deal with their kids learning remotely, too, this fall. And most of all, they and their students will still be operating in a pandemic this fall, and there are limits on what we can do to ensure our people are mentally healthy and well. We're acting like those things aren't there."

That doesn't even account for the possibility, if not likelihood, Jankowski says, that students (and probably some professors) end up having to miss significant chunks of class time (whatever the modality) if they fall ill with COVID-19.

At a high level, what that means is that institutions and instructors should continue to do a few key things in the fall that they did in the spring:

- Listen to students as they make decisions about academic policies.

- Build as much flexibility as possible into their approaches to grading, assignments and deadlines.

- Recognize that students aren't the only ones stretched thin -- instructors and staff members are, too.

More practically, she says, instructors should plan in one-week increments, recognizing that even if their campus has physically reopened, they might have to pivot again in a hurry as they did last spring.

Professors should go into courses with a keen sense of the most important learning they want to impart -- "the really crucial building blocks" for the course -- and pull the key resources to bring that learning alive for students (lectures, readings, assignments, assessments) in a readily accessible, self-contained package. Why? In the likelihood that either a student or the instructor herself gets sick for a meaningful stretch of time. "If I get sick, I need to be able to pass this course on to someone," she says.

Instructors should also try to hold on to the feeling many of them had in the spring that their students needed support, not suspicion.

"We saw the faculty's role in the spring being not about implementing a policy, but about supporting students," Jankowski says. "I'm actually going to believe that what you're saying is happening -- I'm not going to be like, 'Isn't this your third grandma that died?' You can still have policies, but ideally you're telling a student who is struggling, 'You tell me when you can get this done.' Then I don't have to chase you around about a deadline."

The Terrain on the Ground

How grading and academic assessment will actually play out on the ground this fall will vary enormously from campus to campus, balancing continuing flexibility with a desire on the part of many students and instructors to bring back grading.

In a memo to the campus last month, Bowdoin College's president, Clayton Rose, wrote that the liberal arts college in Maine would "return to a standard letter-grading policy" this fall, with "some modifications that will provide you with flexibility in the online learning environment and, for many, a nonresidential semester." Bowdoin had switched to a mandatory credit/no-credit grading policy during the spring.

Jennifer Scanlon, senior vice president and dean for academic affairs at Bowdoin, said in an interview that the overarching policy of returning to letter grading was a nod to the fact that "grades are both a language and a currency for students," some of whom advocated for a return to letter grading this fall. (Four hundred students signed a petition advocating for continuing the credit/no-credit approach.)

The new policy also recognizes that Bowdoin expects the virtual learning it provides this fall to be "vastly different" from last spring's emergency remote learning, building in much more of the relationship-building and peer-to-peer work that the college's students typically benefit from in the physical classroom.

But recognizing that Bowdoin's students will still be in a far-from-normal environment because of COVID-19, the college is adjusting its normal policies to significantly loosen its policy for letting students choose to take a course using a "credit/D/Fail" approach -- allowing that decision to be made until just before Thanksgiving rather than six weeks into the term, and applying it to any one of a student's four courses instead of just one.

Grading adjustments aren't the only changes Bowdoin is making, says Scanlon. The intensified professional development the college is providing for professors this summer is focusing in part on "not just whether we grade or not, but also how we grade and what we grade," she says.

Bowdoin is encouraging instructors to depend less on high-stakes assessments, and Scanlon says she expects that notably fewer courses at the college this fall will have a "final exam that is a huge proportion of the final grade." (Reducing dependence on high-stakes exams can also have the benefit of reducing student incentive to engage in cheating, which some instructors believe spiked during the spring's remote learning pivot.)

Duke University is due to start a mix of in-person, hybrid and online classes next week, and it announced in July that it, too, would largely return to its previous policies regarding letter grades and add/drop deadlines, after expiration of the temporary policy administrators approved last spring gave students the option of choosing a satisfactory/unsatisfactory grade.

"We made those changes largely to help students weather the transition to the unfamiliar modality of remote delivery," says Gary Bennett, vice provost for undergraduate education. This fall, students have "more familiarity with online course delivery," he says, and Duke has "massively enhanced" its mental health and academic advising support for students, given that there are "so many lingering challenges associated with the pandemic."

But in recent weeks, as Duke's various faculty bodies renewed their normal role in setting academic policies, they "have been extraordinarily active in ways I wouldn't have predicted," Bennett says. The faculty council in Duke's main arts and sciences college has approved an amendment to the letter-grading policy that will let departments designate certain introductory courses for mandatory satisfactory/unsatisfactory grading this fall, Bennett says.

"To me," he says, "that's a sign that our faculty want to support our students in this difficult time."