You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

istock.com/damircudic

For years, advocates for online learning have bemoaned the fact that even as more instructors teach in virtual settings, professors' confidence in the quality and value of online education hasn't risen accordingly. Inside Higher Ed has documented this trend in its annual surveys of faculty attitudes on technology going back over most of the 2010s.

Some hoped that by thrusting just about every faculty member into remote teaching, the pandemic might change that equation and help instructors see how virtual learning might give students more flexibility and diminish professors' doubts about its efficacy.

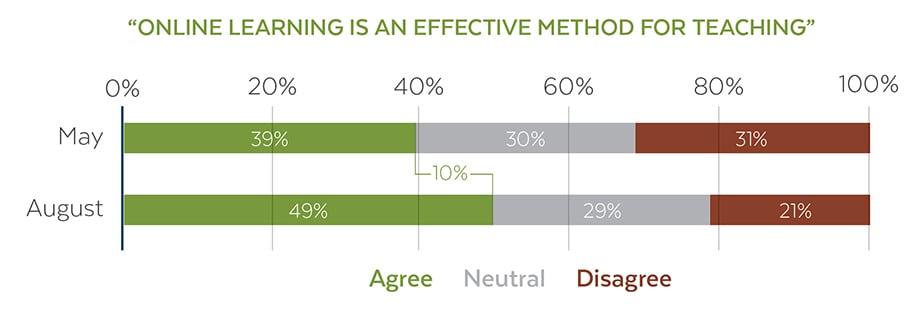

A new survey finds that COVID-19 has not produced any such miracles: fewer than half of professors surveyed in August agree that online learning is an "effective method of teaching," and many instructors worry that the shift to virtual learning has impaired their engagement with students in a way that could exacerbate existing equity gaps.

But the report on the survey, "Time for Class COVID-19 Edition Part 2: Planning for a Fall Like No Other," from Every Learner Everywhere and Tyton Partners, also suggests that instructors' increased -- if forced -- experience with remote learning last spring has enhanced their view of how they can use technology to improve their own teaching and to enable student learning. The proportion of instructors who see online learning as effective may still be just under half -- 49 percent -- but that's up from 39 percent who said so in a similar survey in May.

It also suggests that most professors feel much better prepared to teach with technology this fall than they were last spring -- and they generally credit their institutions for helping to prepare them.

"It's not so much about whether they support online learning now than whether they're more comfortable with the adoption of practices and instructional methods in ways that are really powerful to support student learning in meaningful ways," says Kristen Fox, director at Tyton Partners and project lead on the survey and report.

Historical Attitudes

Faculty skepticism about online learning and other technological approaches to higher education is long-standing -- and arguably well earned. Too often campus administrators or technology advocates have heralded digital forms of higher education by focusing on cost savings or efficiency over quality, or set instructors up for bad outcomes by imposing solutions on them without seeking their input or giving them adequate training.

Even so, pre-COVID-19, more and more instructors had taught online or hybrid courses (the percentage was at 46 percent in an Inside Higher Ed survey last fall). Yet when asked in that same survey whether "online courses can achieve student learning outcomes at least equivalent to in-person courses," fewer than a third agreed.

Every Learner Everywhere, a network of college and technology groups focused on using digital learning to drive equitable access and success in higher education, and Tyton Partners, an investment, research and consulting firm that is part of the network, published the first "Time for Class" survey in July, focusing on how professors adapted (successfully and not) to the sudden shift to remote learning.

This follow-up survey focused on this "fall like no other" and on how instructors and their colleges and universities prepared for it.

The answer is "first and foremost about sentiment," says Tyton's Fox.

In May's first survey, 39 percent of instructors agreed with the statement "online learning is an effective method for teaching," and 31 percent disagreed. When the question was asked of the 3,569 respondents in August, 49 percent agreed and only 21 percent disagreed, with the neutral group remaining about the same size. (About 1,000 professors were queried in both surveys, and 9 percent more of them answered positively in August than in May.)

They cited a variety of reasons why: one community college teacher said that "every student engages (there are no ‘quiet’ students), there’s a degree of flexibility for students, using online resources in place of purchased texts relieves student cost," while another instructor said that her "course content is the most up-to-date it has been in several years with the extra prep I have been doing for the transition online."

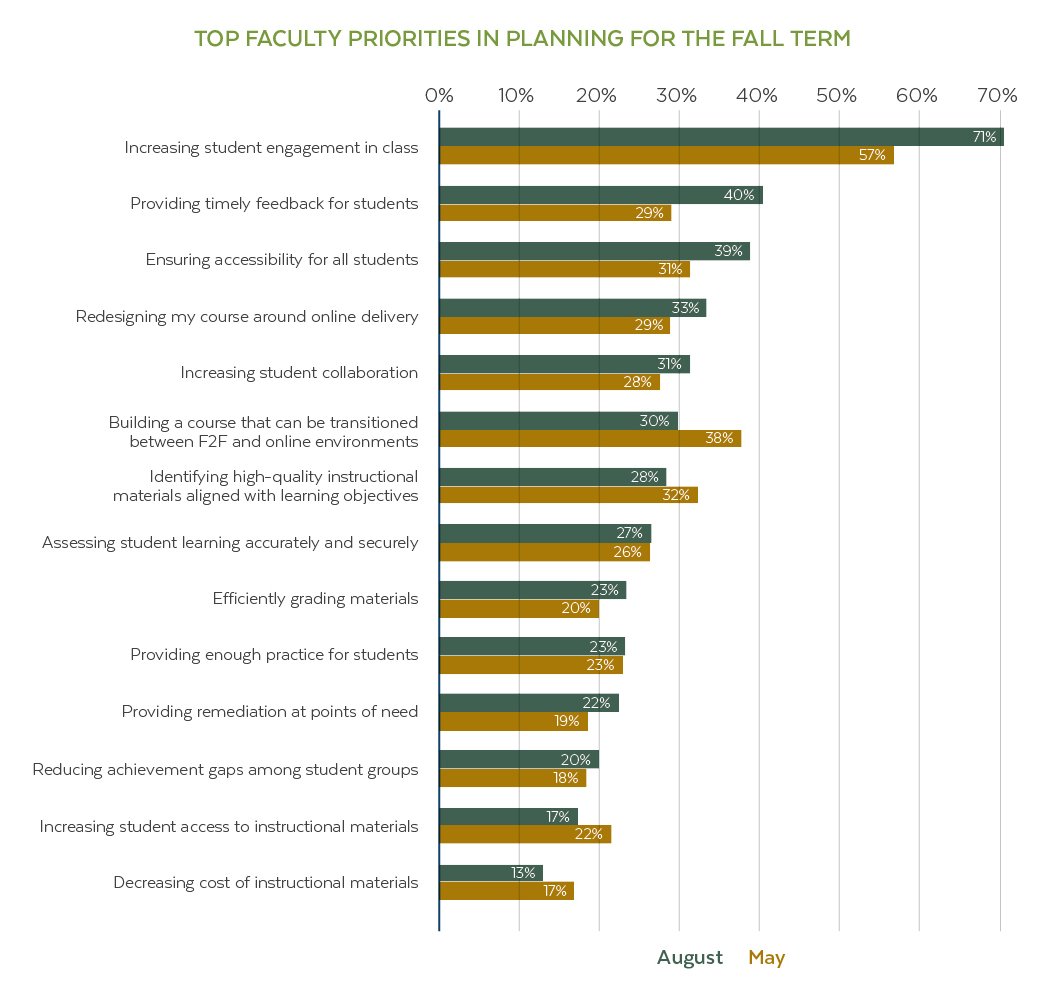

By far the biggest complaint from students and faculty members alike about the remote learning that most experienced last spring was the lack of engagement and interactivity between students and instructors and among students themselves.

So it's probably not surprising that instructors' biggest objective this fall, by far, was to increase that engagement, they say. Among other changes they pursued was to provide more timely feedback and ensure accessibility for all students -- a recognition that students from low-income backgrounds were likelier than peers to lack access to good technology, broadband internet access and quiet places to study, among other necessities for digital learning.

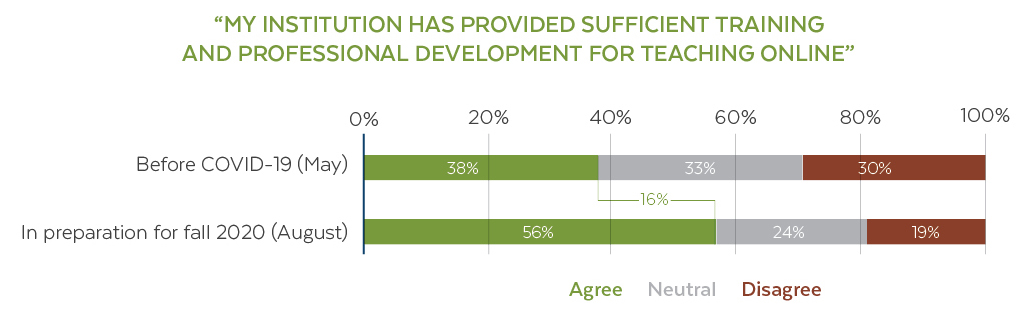

Four in five instructors said they had participated in professional development for digital learning to prepare for this fall, with community college professors (86 percent) more likely than their peers at four-year colleges to say so. Two-year-college instructors were also likelier to say that they were required to participate in instructional professional development, by 40 percent compared to the average of 27 percent.

More than half of instructors credited their institutions with providing sufficient training for the fall, compared to fewer than two in five who felt that way pre-COVID.

Instructors said they turned to a mix of institutional resources and peer support for help -- more than three-quarters said they received aid from instructional technology staff members (78 percent) and peer-to-peer forums (76 percent), while about two-thirds cited teaching and learning centers and instructional designers.

Asked how, with that help, they had redesigned their courses from spring to fall to achieve those goals, more than half of instructors said they had updated their learning objectives, assessments and activities (61 percent) and integrated the use of new digital tools (60 percent), while nearly half (46 percent) said they had embedded "more active learning elements (e.g., group discussion) to enhance student learning and engagement."

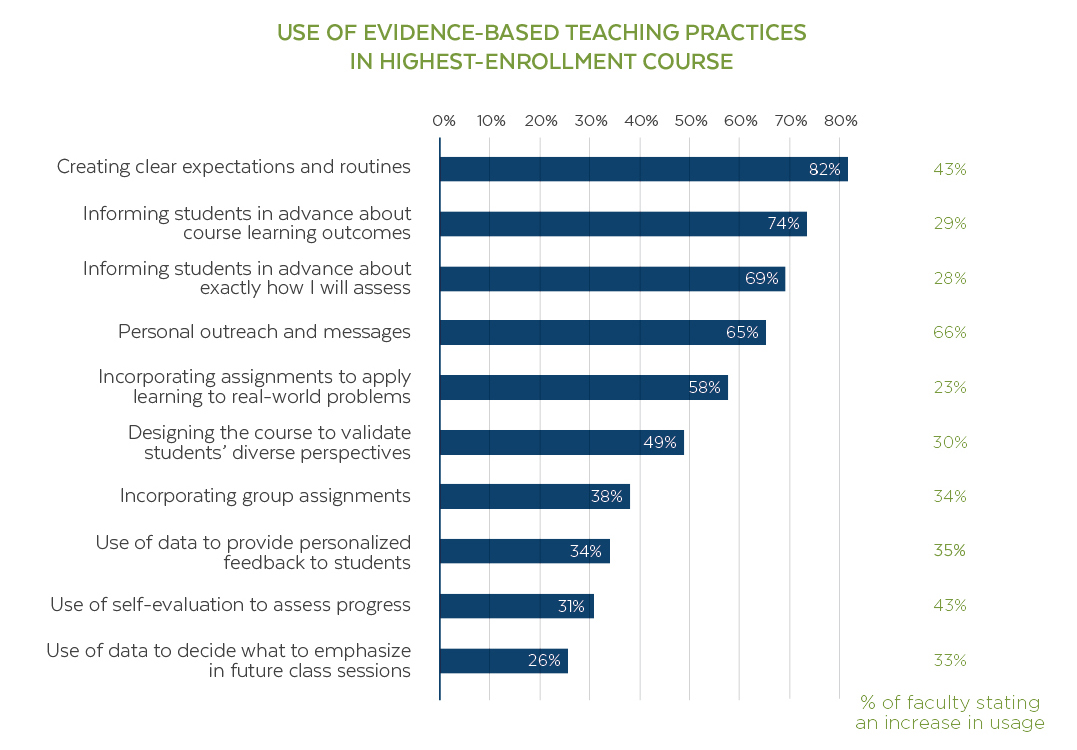

Much larger proportions of faculty members say they will use a set of what the report calls "evidence-based teaching practices" in their largest course this fall than was true the last time they taught the course pre-COVID-19.

For instance, as seen in the chart below, roughly two-thirds of instructors (65 percent) said they would engage in personal outreach and messages to students; that 65 percent represents a 66 percent increase over the last time the courses were taught, the professors collectively said.

These figures suggest that the COVID-19-driven changes in how colleges operate are driving the sorts of pedagogical innovation that critics have long suggested (fairly or not) professors engage in too rarely.

Some of those practices -- like the personal outreach approach cited above -- take significant time and energy and add to many instructors' sense of being overwhelmed, says Fox of Tyton.

She sees some irony in the fact that one of the least-used of the evidence-based practices listed above -- using data to give personalized feedback to students -- could make it much easier for professors to do the outreach they so clearly want to do.

"We hear, 'I want to engage my students, give them more timely and personalized feedback, but it takes so much time to do it right and well,'" says Fox. "If I have 100 students, I'd ideally use the student learning data I have at hand" -- maybe the results of more frequent quizzes, data on who is showing up in class or logging in to use the content -- "to figure out how to triage and intervene in ways that aren't killing me as a faculty member."

Many faculty members know how to do that in the physical classroom, Fox says, relating a commonly heard faculty comment: "I know how to read the face of a confused and struggling student."

Doing so in a different format is a "learnable, teachable skill that faculty are asking for" and that colleges could help with, she adds.

Hopeful for Fall

All of the changes that instructors have made, with all of the help their institutions have given them, had professors stepping into their classrooms -- virtual or otherwise -- pretty confident this fall. About three-quarters of those who were preparing to teach online (74 percent) and those who were preparing to teach fully in-person (73 percent) agreed with the statement "I am prepared to deliver a high-quality learning experience to my students this fall," while about 10 percent disagreed.

Those who were preparing to teach in hybrid or other "flexible" formats were slightly less confident, with about two-thirds saying so.

"This reflects the unique challenges of these delivery modes and the need to better support and share best practices for mixed-mode course delivery," the report states.

Worries Remain

Lest anyone think most instructors have gotten overly confident in their own abilities or the efficacy of their colleges and universities, however, many faculty members believe they have a long way to go in delivering technology-enabled learning that meets their students' needs.

Professors' support for the statement "my institution is achieving an ideal digital learning environment" (How many faculty members would say anything at their institutions is ideal?) climbed noticeably from the spring, with a particularly sharp rise among two-year institutions. This is "an outcome of the herculean efforts that many across higher education have made," the report states.

The area of largest concern for many faculty members appears to revolve around equity. Professors' lists of the top challenges their students faced in the spring, and are likely to face in the fall, included things like fitting coursework in with home and family responsibilities, managing student mental health and wellness, ensuring reliable internet access, and managing financial stress in light of COVID-19.

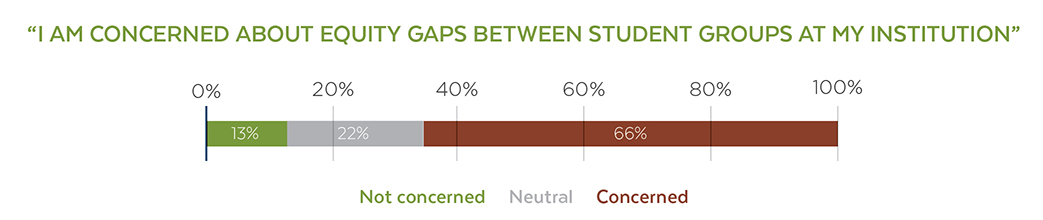

Most of those challenges disproportionately affect students from low-income and other disadvantaged backgrounds, which is why two-thirds of surveyed instructors said they were concerned about equity gaps.

Fox and the report's other authors find an almost hopeful note in that concern about equity, which they suggest may be a silver lining to the hardships presented by COVID-19: "greater empathy for and understanding of the challenges faced by students."

"As soon as we made the decision to go fully online last March, there was a clear difference in success rates for the rest of the term because of access to technology, equipment, and internet," the report quotes one community college faculty member as saying. "It was frustrating and heartbreaking to see which students struggled to manage the class. This is the biggest hurdle we face. Making online classes is hard, but not as hard as making sure everyone has equal access."