You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The disruption wrought by COVID-19 seems like it should have created fertile ground for the spread of the freely available, openly licensed course materials known as open educational resources, or OER.

With students physically dispersed and under greater-than-ever financial strain, faculty members were likelier than ever before to use e-textbooks and other digital materials to keep students connected. And colleges ramped up the sort of professional development that tends to make instructors aware of new curricular approaches, which often include open education.

The latest iteration of an annual survey on the state of open educational resources, released today, shows that is what happened -- but only up to a point.

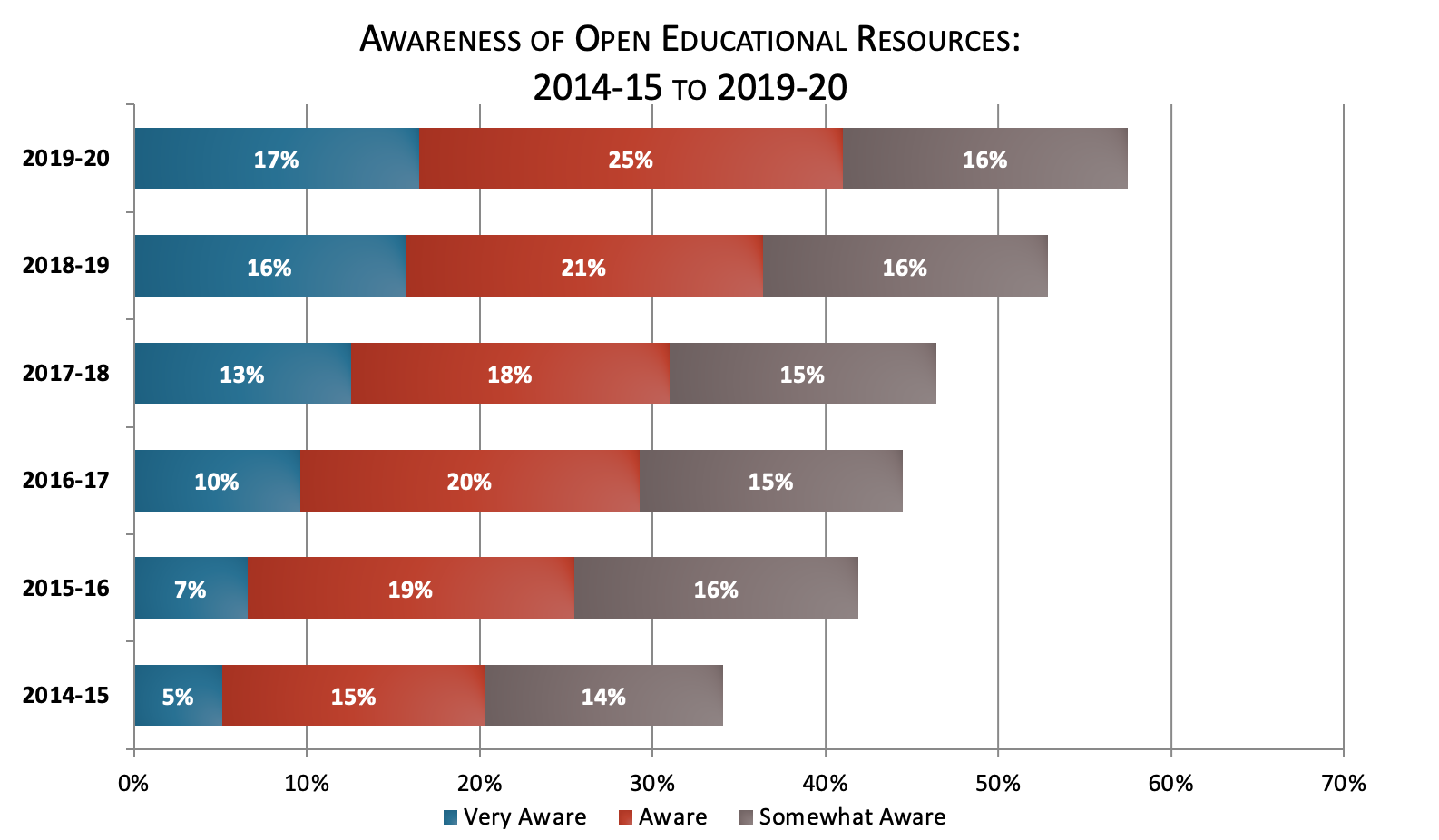

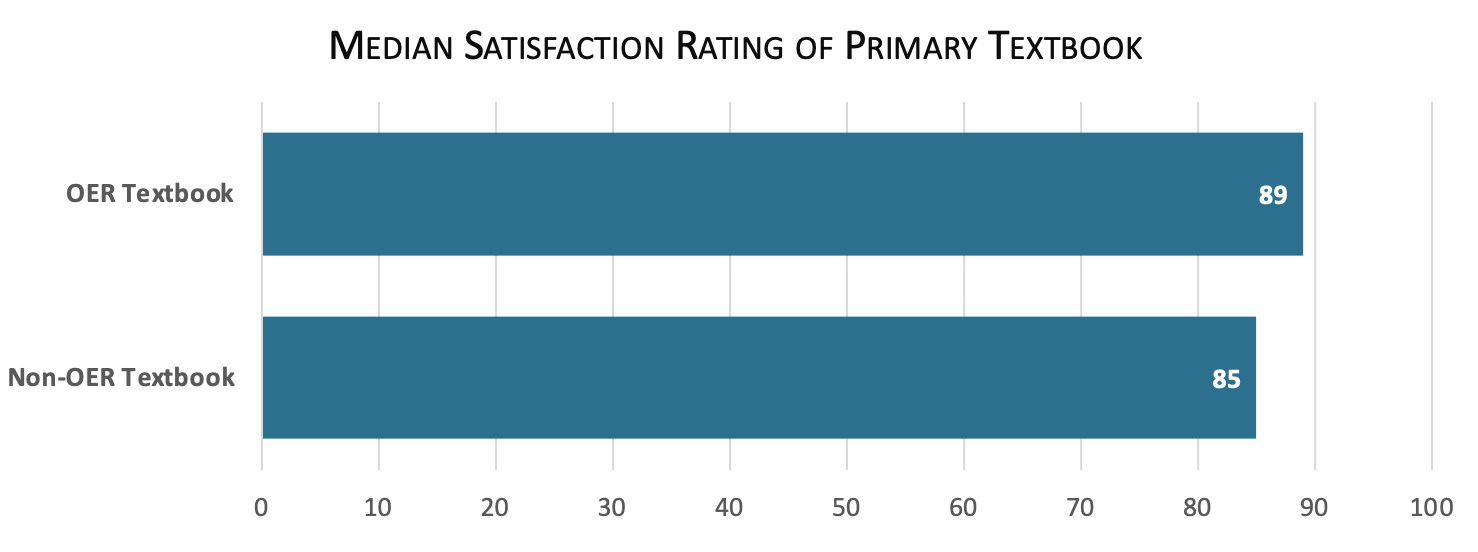

Faculty awareness about the existence of open educational resources in 2019-20 continued the steady arc of growth seen in recent years, growing by about five percentage points from the year before, to nearly six in 10, according to "Digital Texts in the Time of COVID," by Bay View Analytics on behalf of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. And professors' belief in the quality of OER rose, too -- slightly surpassing their satisfaction with commercial textbooks.

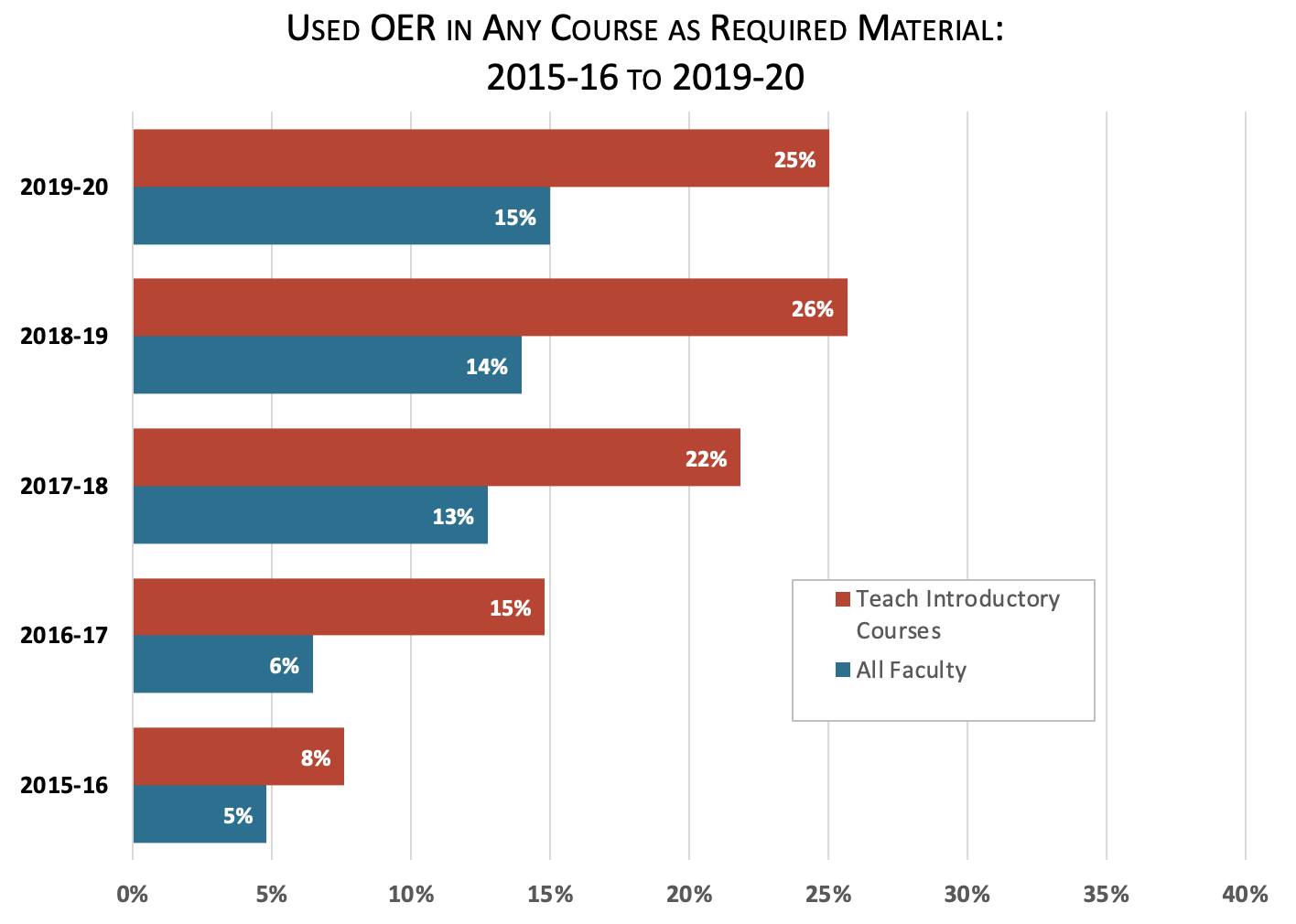

Despite those changes, which should bode well for use of OER, the proportion of instructors who said they had required the use of open resources -- the ultimate signal of embrace -- did not budge from 2018-19, remaining at about one-quarter of all faculty members.

A couple of factors could explain why OER adoption did not climb as awareness did, as has been the case as long as Jeff Seaman, the report's author, has been tracking these data.

The survey found that the vast majority of faculty members (87 percent) used the same primary textbook in their fall 2020 courses as in previous terms, and Seaman posits that "the full range of adjustments that faculty had to cope with in changing to online instruction may have fully occupied them, restricting the time" they might have spent exploring alternatives such as OER.

They also might have wanted to avoid inserting another unknown into courses that were already going to be radically different for students struggling with all sorts of extra challenges, Seaman says.

Defining OER

The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, citing Creative Commons, defines open educational resources as "teaching, learning, and research materials that are either (a) in the public domain or (b) licensed in a manner that provides everyone with free and perpetual permission to engage in the 5R activities– retaining, remixing, revising, reusing and redistributing the resources."

Those factors, among others, would suggest that OER adoption could be poised to accelerate as instruction returns to something slightly closer to normal for professors and students alike next fall and beyond.

But another reason OER adoption might have lagged during the pandemic bodes less well for the future of open educational resources. The accelerated shift to digital curricular materials didn't just benefit free and open course materials; commercial publishers have increasingly shifted their business models to focus on digital courseware, and they have spent heavily on new products aimed at winning over campus administrators who want to reduce what their students spend on textbooks but also require students to pay for textbooks up front to ensure they have access to the material.

"We just don't know yet who benefits most from a more aggressive shift to digital: OER or the publishers?" Seaman says.

Upward Arc for OER

The last few years have seen open educational resources play a steadily growing, if still limited, role in how faculty members teach and college students learn.

In 2015-16, 5 percent of all instructors and 8 percent of those teaching introductory courses reported using OER as required material in their courses; in Seaman and Bay View's 2018-19 survey last year, those figures had risen to 14 percent and 26 percent, respectively.

Several factors drove that growth. Increasing public pressure about affordability has forced many college administrators and professors to pay attention to what they charge students, and institutional leaders have had incentive to focus on areas such as textbooks, where the money flows not to the institutions but to third parties such as publishers.

Some states and many individual colleges -- and even the federal government -- have seeded initiatives designed to fund the creation and build the awareness and ultimately adoption of high-quality open materials, as have philanthropies such as the Hewlett Foundation.

Those collective efforts have moved the needle for OER at a time of great upheaval in the textbook market, but wide embrace of open educational resources has been held back by another set of factors: lack of awareness; faculty inertia (building open resources from scratch, like many forms of experimentation, can be time-consuming); doubts about the quality of OER materials (fed in part by commercial publishers who invest heavily in supplemental teaching materials that many OER producers struggle to match); and the diffusion of the OER marketplace and the lack of central structures and advocates for open materials (there is no equivalent to the Association of American Publishers in the OER world, let alone Pearson or McGraw-Hill).

Impact of the Pandemic

The onset of COVID-19 upended the instructional landscape in higher education in many ways, and surveys like the most recent iteration in the Bay View series on OER help to illuminate how.

The survey of 3,232 postsecondary instructors found that about two-thirds had changed their fall 2020 courses considerably (24 percent) or moderately (44 percent) since they had taught it before, with the changes overwhelmingly related to demands of the pandemic. Professors described changing all sorts of things: assignments, activities, assessments, interactions, office hours, delivery mode.

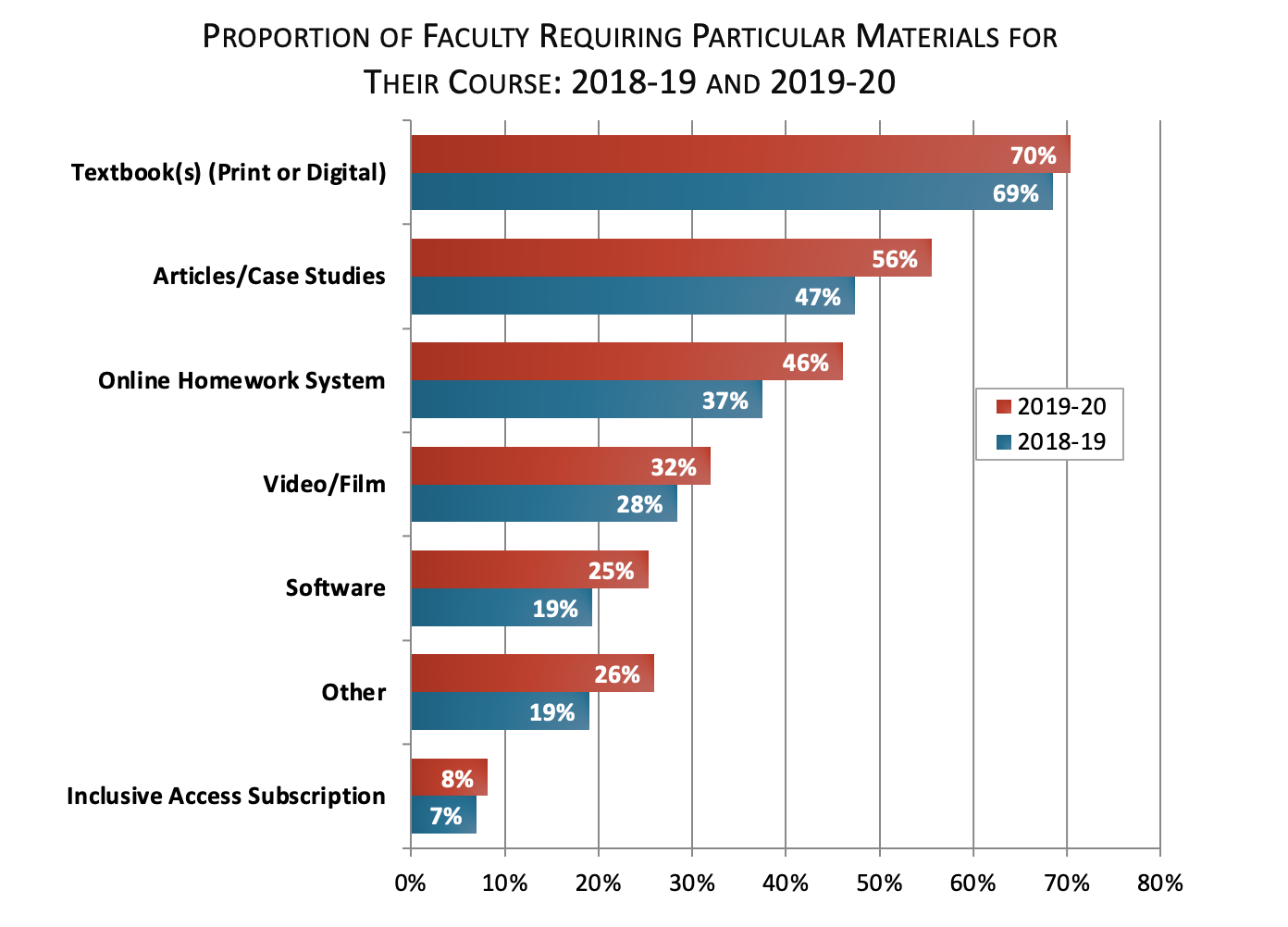

Amid all those changes, the course materials professors used shifted relatively little. While instructors were a good bit likelier in 2020 than in 2019 to say they used articles or case studies, online homework systems, and software, they were similarly likely to require a textbook -- about seven in 10.

Nearly nine in 10 instructors (87 percent) said they used the same textbook in 2020 they did in 2019, though about a third added a digital option for students, and 10 percent switched entirely to a digital format.

Faculty (and student) embrace of digital textbooks and course materials has been slower than many technology advocates', and the pandemic-driven digitization of instructional delivery didn't appear to change perceptions: roughly the same proportion of instructors, 43 percent, agreed (somewhat to strongly) that "students learn better from print materials than they do from digital" in 2020 as answered that way in 2019 (44 percent). About a third also said they believed their students preferred print materials over digital, the same as the year before.

Awareness and Adoption

Faculty awareness of the existence of open educational resources has been climbing steadily, and it continued that arc in 2019-20, with nearly six in 10 professors expressing at least some awareness.

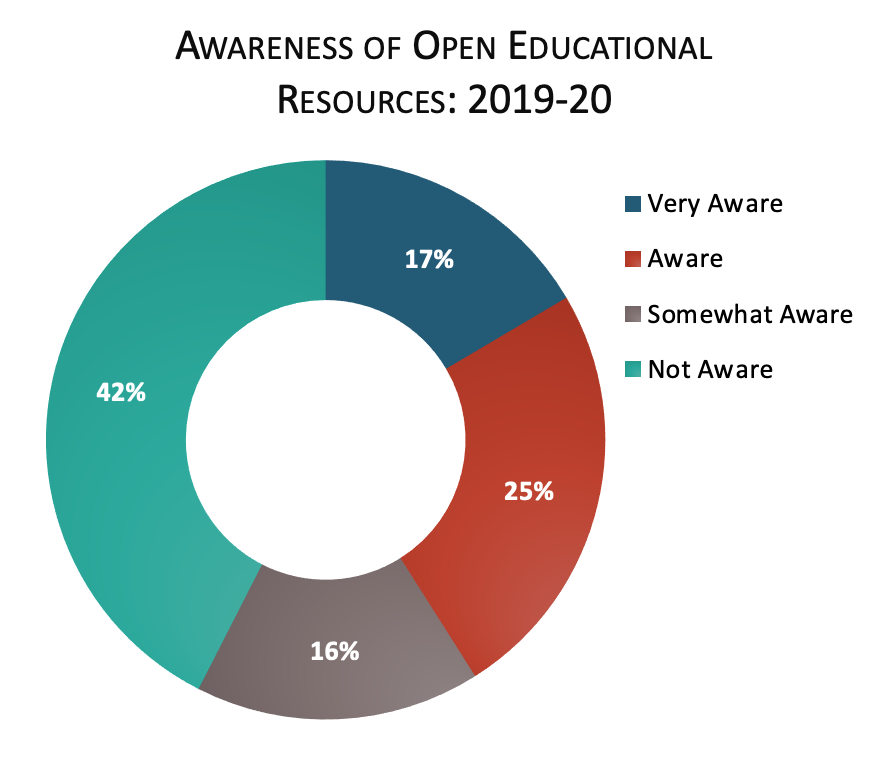

The proportion of instructors describing themselves as "very aware" of OER has more than tripled since 2014-15, while 42 percent of instructors reported having no awareness of OER in 2019-20, down from a full two-thirds in 2014-15, as seen below.

(Bay View's series of reports on OER also uses a stricter definition of "awareness" that factors in professors' knowledge [or lack thereof] about licensing of copyrighted material. Professors who both say they know what open educational resources are and are familiar with the kind of Creative Commons licenses under which OER are usually shared are truly deemed to know what open resources are, and that proportion climbed to nearly half in 2020.)

Awareness of OER appeared to increase even though faculty members in 2020 were no likelier than in 2019 to report being aware of initiatives at their institutions to inform instructors about the resources. The exception was among professors at minority-serving institutions, who were several percentage points likelier than professors elsewhere to say they were aware of OER initiatives at their institutions or university systems.

The increased awareness of open educational resources, however, did not translate to increased adoption of OER as required materials in the year of COVID -- which the report describes as a "plateau." The report did note a modest increase, to 28 percent from 26 percent, in the proportion of instructors saying they used OER content as supplemental rather than required materials.

Jodie Steeley, director of distance education and instructional technology at California's Fresno City College, said it was unsurprising that instructors didn't see the pandemic as a time for experimentation.

"Faculty had to choose their textbooks for fall 2020 in April 2020, most likely defaulting to what they used before, especially if they had never taught online before," she said via email. "They had roughly four weeks to make a choice while their personal and professional lives may have been causing anxiety and even panic. Relying on what they were highly satisfied with before the pandemic and what they expected to be satisfied with after, was comforting, and in many cases, necessary from their point of view."

What happens next, though?

It is feasible, even logical, that the increased awareness of OER instructors developed during COVID will mean that when they have a chance to catch a breath as the pandemic slowly recedes, they will be more open to experimenting with open educational resources. That's particularly true if, as other surveys suggest, professors' compulsory experiences last year with remote learning have made them more comfortable teaching in digital environments, and colleges increase their use of online and blended education going forward.

The pandemic also appears to have greatly increased instructors' sensitivity to their students' situations and challenges, giving them (often literally) a glimpse into their homes and their personal lives. Lastly, colleges and universities face intensifying pressure to make college more affordable and welcoming to learners from disadvantaged backgrounds, and advocates for OER argue that free, and openly available, course materials are a key prong in those efforts.

Of course, textbook publishers argue that their own efforts to make course materials more affordable -- through inclusive access programs, among other ways -- are a better approach, and have the added benefit of being of higher quality.

That argument, though, seems to be losing steam, at least among respondents to the Bay View survey. When asked to assess their satisfaction with the primary textbook they used in their courses in 2019-20, the median rating was higher for OER textbooks than for others.

That finding doesn't meant that the "quality" issue has evaporated in the battle for the hearts and minds of instructors (and students) over course materials. But as awareness of open educational resources grows along with pressure on colleges and instructors to find affordable, equitable course materials for their students, perceived quality may be less of a barrier for OER to overcome.