You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Few ideas about higher education change have been as influential as those of Everett Rogers. His Diffusion of Innovations, first published in 1962 and now in its fifth edition (2003), has helped generations of university change agents think about their work.

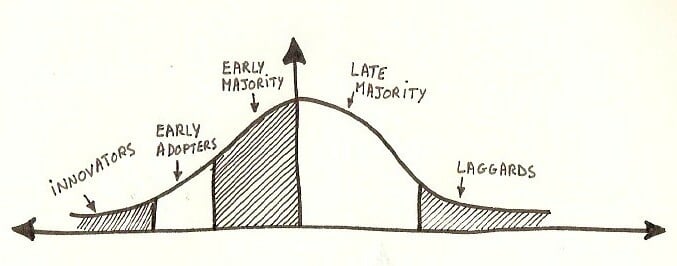

There is perhaps no more iconic image to explain how higher education innovation occurs, and to guide university innovation initiatives, than Rogers’s famous innovation adoption curve.

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/wfryer/1342355056

This bell-shaped curve has been reproduced in countless presentations, blog posts and articles about higher education.

The idea that universities are places that are populated by individuals (and particularly faculty members) who fall somewhere along a normally distributed innovation curve is so widespread as to go almost unnoticed. The normally distributed curve of “innovation readiness” is so ingrained in much of the thinking in higher education that it is assumed to be a starting place for any change initiative.

The thinking goes that certain at least half of university stakeholders -- again, mostly professors -- will start out to the right of the innovation readiness curve. About 34 percent will be late majority, and 16 percent will be laggards. Only 13.5 percent of university people are thought to be early adopters, and only 2.5 percent can be considered innovators.

The standard advice that comes out of Rogers's adoption curve is (a) don’t spend your energy convincing laggards to change, as they never will, (b) find the innovators and the early adopters and make common cause with them, and (c) the early majority will bring along the fence-sitters, and therefore they are the group that will require the most attention.

When innovation higher education change efforts don’t work out as planned, the reasons are often ascribed to the difficulties of convincing an entrenched set of late adopters and laggards to change.

But what if this model is wrong? What if the idea that people have a predisposition to innovation readiness, and that these traits can be mapped across a normal distribution, has no actual basis in reality?

Could it be that a simple image, divorced from the nuance and complexity of how Rogers actually wrote about how innovations are diffused within organizations, has clouded our thinking about higher education change for the past few decades?

We think so.

The reality is that the idea that certain people, and particularly certain higher ed people (the professors), are more or less open to innovation is a myth.

There is no single personality type or attitudinal predisposition that makes one higher ed person more pro-innovation than another.

Instead, folks in higher ed -- like everyone else -- have attitudes and ideas that are shaped by a mix of complex structural forces, cultural norms and incentives. These external forces interact with internal beliefs and motivations to guide behaviors.

Higher ed people, like everyone else, may champion change in one aspect of their academic professional lives while fighting change in another. The laggards in one area of university innovation efforts may be the early adopters in another.

The same people will fall all over the innovation adoption curve. Placement along this innovation continuum is not a stable personality trait. The labeling of some in higher education as laggards in areas of innovation erroneously assigns actions to individual beliefs while neglecting structure and incentives.

If the idea of “innovation readiness” is a myth, what does that realization mean for those who wish to lead university innovation initiatives?

How should it change our thinking and our actions if we abandon the idea that there will always be some proportion of stakeholders that will always start as late adopters and laggards?

Mostly, we recommend that the job of the university innovator is to listen.

The biggest mistake that someone who wants to change their institution can make is to not listen to those who are skeptical of those changes. Start with the awareness that those who are skeptical of your innovation initiative may be highly innovative in some things that they are doing. Abandon the idea that your critics are against change, and instead realize that they are against the change that you are proposing.

This is not to say that those within higher ed who push back against new efforts and changes to the existing operations and methods are correct. Our colleges and universities need to change. We need to address persistent challenges of costs, attrition and quality.

Rather, we need to stop placing the blame on those of who we think of as late adopters and laggards for opposing higher ed change.

These people don’t exist.

Instead of looking at reasons based on personality type to make sense of why our innovation efforts are unwelcome on campus, we should look at the quality of our own programs and efforts. Rather than blaming those who fight campus change on an unwillingness to try new things, we should focus on gathering and communicating the data that will support our efforts.

It is time we let go of the idea that some of our colleagues are more innovative than others.

Don’t even get us started on the myth that certain people are the big “vision” people.