You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

In fall 2013 approximately 27 percent of the 17 million undergraduates in the United States engaged in some form of distance education. According to the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics, of that 27 percent, more than 11 percent were pursuing their education exclusively online. Despite phenomenal demand for online courses, Inside Higher Ed’s 2016 survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology reports that the majority of faculty members believe that online courses are incapable of achieving learning outcomes equivalent to face-to-face courses.

Trained to explore, experiment, analyze and innovate, one might expect academics to meet the challenge of creating rigorous online courses with a “can do” attitude. Yet, I often encounter tenure-track faculty members who are skeptical about our ability to “do history” or most any other discipline, for that matter, online. Others are openly hostile to online.

I find it hard to sit still in meetings where faculty members operate from a baseline assumption that online is, if not evil, at least regrettable. I love teaching online. Although I cut my professional teeth in face-to-face settings -- and loved that, too -- I’ve been somewhat surprised by how much I enjoy teaching and interacting with students online. Why don’t my colleagues share my enthusiasm?

Certainly some of the reticence and resistance stems from unfamiliarity. Indeed, faculty resistance to online education is most pronounced among those least experienced with teaching online. Others fear their unfamiliarity with the technology will make teaching online a logistical nightmare. Faculty members are no different from other humans in this respect. We all can find the prospect of shifting to new, unknown processes daunting.

Faculty resistance to online, though, is also fortified by a mythologized, or at least sentimentalized, vision of the quality of face-to-face teaching and learning. For many, “online” connotes “decline” largely because we’ve reimagined the in-person classroom as a wood-paneled utopia where wide-eyed students probe the mysteries of the universe in a dreamy haze of pipe smoke and lemon polish. Grade inflation and a lack of reliable evaluative tools can serve to mask much of what is happening in the face-to-face classroom.

While faculty members are certainly as susceptible as anyone to fear and myth, much of their resistance to online education reflects a deeper anxiety that has little to do with the actual merits of online education. Rarely articulated clearly, much of the faculty reticence I’ve encountered stems from a sense that online education threatens faculty control. Such anxiety is justified. Yet responding to online education with indifference or disapprobation isn’t the answer. Indeed, such responses might actually be harmful.

How should faculty respond to the online juggernaut? They should teach online. Now … before it’s too late. By avoiding or rejecting online education faculty ignore its proven benefits and forfeit control over one of the most potent developments in higher education in the last 50 years.

The Rise of the Online Enterprise Group

The proliferation of online education has utterly transformed the dynamics governing the educational process. In the not-too-distant past, faculty developed courses in relative solitude. They might have sought permission from a department chair and, perhaps, waded through a college-level approval process, but after that, they were on their own -- free to make decisions about content, delivery, and assessment.

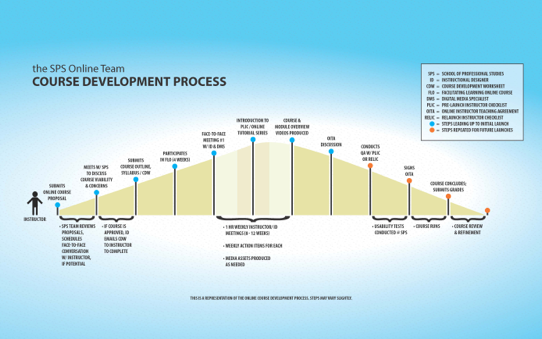

This rise of online education has reconfigured the course development process and blurred faculty oversight of curriculum and instruction. Bringing a course online often requires faculty members to move outside the academic unit into a collaborative space populated by instructional designers, technology specialists, and distance education administrators, as well as external vendors who partner with the university to deliver software and student management services. (Figure 1, from School of Professional Studies Online Team, “Course Development Process,” Brown University.) This group, which we might think of as the “online enterprise group,” is the product of a significant redistribution of resources that has reverberated across campuses.

In some instances, this reconfiguration has produced structures that have improved teaching. For example, one consequence of the emergence of the online enterprise group has been an infusion of instructional design professionals into higher education, a development that has certainly improved my teaching. Instructional designers I’ve worked with have helped me think more clearly about course organization, instructional strategies, learning outcomes, and student engagement. Their presence has provided me with professional feedback I would not likely get teaching on ground unless I asked for it or I was up for tenure.

But such benefits do not outweigh the serious threat the online enterprise group poses to faculty governance and to the health of liberal education.

Online education Isn’t the Problem

Before addressing the real threats posed by the online enterprise group, it’s important to acknowledge the social benefits of online education in order to clarify a distinction many faculty members have trouble seeing: Online education, in and of itself, is not the problem. Instead, I’m arguing that the threat resides in the structures that have arisen to deliver online education, that is, the online enterprise group.

There are a host of reasons faculty should engage in online education, not the least of which is that it is effective/ While data continue to pour in, recent analyses clearly demonstrate that an online educational environment can be conducive to learning. In Learning Online: What Research Tells Us About Whether, When and How, Barbara Means, et al, looked at 45 studies comparing college learners in online and face-to-face conditions and found that “In most meta-analyses of controlled studies comparing learning outcomes for online and face-to-face instruction, those who learn online fare as well as, and sometimes even better than, those experiencing the instruction in face-to-face format.” Recent studies of student discussion demonstrate that the online modality not only results in broader participation, particularly among students from underrepresented groups, but that it encourages deeper understanding, more reflection, better recollection of core concepts, and an enhanced willingness to apply learning to new issues.

Faculty members should also engage in online education because it’s the socially responsible thing to do. While we certainly continue to face challenges in serving students from certain sociodemographic groups, comparative data make clear that the online option is bringing not only more, but different students into the program I direct. (Fig. 2) The transformative potential of this shift is important. In interpretive disciplines like History, where the questions scholars ask and the topics they explore are often shaped by personal history, this diversification could result in a more nuanced understanding of the past and in the evolution of a professoriate better situated to prepare students for success in a multicultural and global society.

|

Arizona State History MA Students |

Online |

Face-to-Face |

|

% Non-traditional (>30 years of age) |

72 |

23 |

|

% Female / % Male |

42/58 |

31/69 |

|

% Parents without degrees* |

29 |

23 |

|

% Nonwhite |

15 |

8 |

|

% Working full-time |

65 |

31 |

|

% Veteran |

14 |

8 |

The Threat to Faculty Governance

Despite the clear benefits of online education, the structures surrounding online education pose a real threat to liberal education. While the landscape is complex, many of the universities and colleges that are leading the evolution of online education have adopted highly centralized administrative models that transcend academic departments. Rather than a service unit tasked with assisting faculty—something akin to a university technology office—these online enterprise groups are an increasingly powerful force in decision-making about curriculum, pedagogy, and program management.

Often standards and assessment measures are designed without faculty input and implemented without the consent of academic units. It is worth noting that such training and oversight typically have no corollary in face-to-face programs.

By failing to actively engage in online teaching, faculty members limit their ability to meaningfully contribute to online decision-making and to ensure that the values that have traditionally informed liberal education are not superseded by those guiding the online enterprise group.

Driven to improve the capacity of the university, the online enterprise group operates within a client/provider framework that values doing things better, cheaper, and faster. Its value system prioritizes scalability, standardization, linearity, functionality, and quantification. Faculty and academic units are sometimes referred to as “content providers” in this framework.

But the online enterprise group doesn’t just have a different vision of how to deliver education; its members advance a vision alien to liberal education. To wit, two thirds of the undergraduate and graduate degree or degree completion programs offered by IU Online, the online enterprise group at Indiana University, focus on STEM fields, health care, business/communication, and criminal justice. Nearly three-fourths of UF Online offerings, from the University of Florida, are in STEM fields, health care, business/communication, and criminal justice. Neither UF Online nor IU Online offers undergraduate degree programs in the humanities.

The issue of scaling points up how the priorities of the online enterprise group might threaten liberal education. One of the core functions of the online enterprise group is to scale up course delivery, capitalizing on the assumed efficiencies of economies of scale. While it is true that auto-graded quizzes and adaptive learning software can improve learning by providing students with immediate feedback without the capital expense of additional instructional personnel, automation works better in some disciplines than others. No amount of technology can offer a student meaningful feedback on the quality of his evidentiary materials or the logic of her argument.

The online enterprise group’s scaling imperative can have real consequences for writing-intensive disciplines like history and literature because writing-intensive assignments cannot be automated and are labor-intensive from a faculty standpoint. So, faculty members facing a proviso that insists that online courses be developed with “unlimited enrollment capacity,” as ASU Online’s “Memorandum of Understanding for Online Course Development” requires, will have a tough decision to make. Scaling up in the humanities means either significantly more work for the instructor or instruction that jettisons the crucial processes of analysis and appraisal.

As the example of scaling highlights, in dictating the how of online education, the online enterprise group is increasingly dictating the what of online education. Less visible disciplines that don’t have strong vocational identities or whose methodologies aren’t conducive to automation are inherently less appealing to the online enterprise group.

This makes faculty participation in online education absolutely imperative. This engagement needs to happen on two fronts. First, faculty members, especially those on the tenure track, should snap up opportunities to teach online. Such a suggestion may seem counterintuitive to those anxious about the ways online education seems to be changing the academy. But how can we reasonably hope to align online education with liberal education if we lack understanding of what online teaching looks and feels like and if we don’t have a sense of our online students? In short, we need to know the terrain if we hope to be involved in discussions about how best to occupy it.

Second, faculty members should engage in dialogue and cultivate leadership around the issue at the university level through such entities as university or faculty senates. Few institutions have clear statements articulating the governance boundaries and relationship between faculty and the online enterprise group.

More than 10 years ago the Academic Senate for California Community Colleges began exploring the challenges posed by corporatizing trends in higher education and the role that online programs played in such trends. While the issue has blossomed somewhat in the academic press, similar conversations have been painfully slow in coming to Research I institutions. As a colleague at another university recently admitted to me, her university faculty council is just now beginning to ask questions about faculty governance and online programs -- some six years after her institution created a centralized administrative unit to oversee online education.

For a number of reasons, it is important that such dialogue and leadership occur across the faculty, rather than at the departmental level. The fragmented nature of many large Research I institutions, particularly those with multiple branch campuses, makes it all too easy for the online enterprise group to avoid faculty oversight. As Jonathan Rees notes, if an individual faculty person on one campus proves uncooperative or challenges existing operating procedure, the online enterprise group can always approach a more compliant faculty person on another campus. Departments and even individual faculty members become competitors, rather than collaborators, in a marketplace controlled by the online enterprise group.

Departmental administrators exacerbate the problem by allowing track faculty to opt out of teaching online. Whether promoted by the online enterprise group or at the departmental level, tenure-track faculty members’ absence from online education has sanitized the labor pool and ensured that the online enterprise group rarely has to deal with people in positions of power who have reservations about the curricular and labor systems currently governing online education.

The effort to align online education to liberal education will be an arduous and risky task. In an era of state disinvestment in higher education, particularly in the humanities, the revenue generated by online courses functions as a powerful disincentive for disrupting the existing system. Nevertheless, faculty must become active agents in evolving new models if liberal education is to survive.