You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The University of Colorado at Boulder has partnered with Coursera on an affordable scaled master’s degree that returns to the essential mission of disruption in the MOOC format. The pilot launched last October, and the next tranche of courses began in January 2020. This article is the second in a series tracking the development of the degree as it rolls out over 12 months. The first appears here.

***

In early spring 2013, back in the sanguine days of utopian MOOC disruption, I received an email from the provost drafting me into University of Colorado at Boulder’s pilot run on Coursera. The provost had a gutsy idea: pair Coursera’s then-avant-garde modality with my Comics and Graphic Novels lecture and see what disrupts. After googling “MOOC” and amusing myself with a few Mean Streets video clips, I accepted his challenge. What else was I going to do?

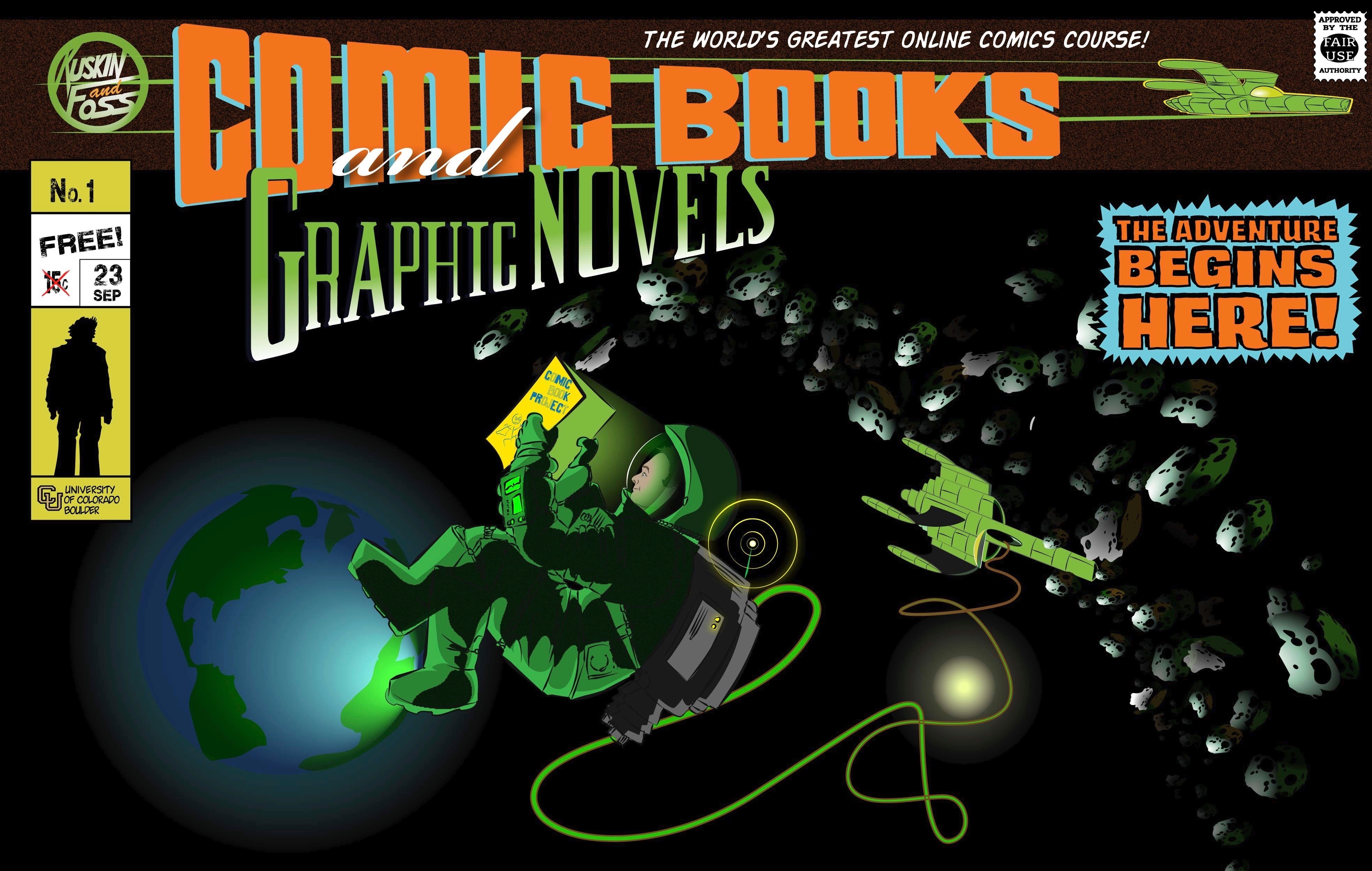

Since my course featured a DIY comic assignment, I thought, all things being equal, I would make a comic, too, or at least I would commission one, a story that would play with my role as a test pilot and with the idea that MOOCs were a disruptive force in higher ed.

I reached out to CU Boulder M.F.A. graduate and good friend Tim Foss. Together, we designed the course homepage as a comic book cover (image one) and created a story that unfolded with each week’s lessons. The first week had me inducted into the test pilot training camp and then blasting off from a launchpad hidden in the tower of CU Boulder’s iconic Old Main building.

The story continued with me crash-landing into a very similar-looking building on a different planet, seeding an eventual Planet of the Apes plot twist. In the third week, I discovered that my crash had, in some strange way, destroyed this planet’s icons of higher learning (image two). The rest was an adventure in the world of disrupted higher education.

Three weeks into the MOOC, I looked at the homepage and felt like a space oddity indeed, cut off and floating, isolated from my 38,000 students, like Bowie’s Major Tom, detached: “‘Here am I floating round my tin can/Far above the moon/Planet Earth is blue/and there’s nothing I can do.’” Herein lies the critique of the MOOC universe: not that MOOCs didn’t successfully take off but that their massive nature fundamentally alienates its users so that, after the initial fanfare, the circuit’s dead and the educational message never reaches its audience.

***

Over the fall semester, the University of Colorado at Boulder piloted the first three courses in its at-scale M.S. degree program in electrical engineering. At the start of the pilot, I wrote about the degree’s plan to follow the disruptive mission of those early MOOCs through two major innovations: a modular and stackable curriculum hosted entirely on the Coursera platform in which the for-credit courses sat on top of the noncredit courses, and a performance-based admissions system.

In the process of building the pilot, we discovered that we also had to build a system for automating student enrollment. This became a third, emergent innovation, one that involved the entire university system in a major challenge of coordination.

In October we launched the pilot program of three courses, capped at 75 enrollments each. One hundred and fifty-two of these were domestic students, 140 of whom were from outside of Colorado; 64 were international students (the geographic count is different from the total count because some students took multiple courses). Coursera fulfilled on its promise of global reach.

Preliminary Data

The pilot officially came to a close at midnight, Mountain Time, New Year’s Eve 2020. Given the amount of data generated by the Coursera platform and by our own surveys, it is early for an entire review, which is more fitting a longer study. The results I present here are tremendously preliminary and general. I break them down into two main categories: system integration and student performance.

- System integration: A major task of the pilot was integrating Coursera’s enrollment management system with the university’s, including enrollment, billing and identity provisioning. At the beginning of the pilot, the enrollment process -- from expression of interest to provisioning students with a university identity -- took 24 hours, a significant improvement in speed over the traditional process, much of which is done by hand. Toward the end of the pilot, when we began to enroll students in the second cohort, we had this time down to two hours, start to finish.

- Student performance: A graduate program should publish its completion data. Before I present this data, I would like to underscore that the M.S.-EE’s performance-based admissions system aggregates the recruitment funnel, admissions, enrollment, melt and retention into a single process designed for global access. Anyone in the world can enroll in noncredit courses and, because the courses are asynchronous, can then elect at any time during the course’s duration to stack the for-credit courses on top of them.

There is no official census date in the M.S.-EE program. Rather, there is a very flexible learning environment in which students may withdraw until the very end, as they realize they are not prepared for graduate study or encounter personal constraints. In a performance-based system, coursework does the work of sorting students out, which complicates any clear calculation of admission rate, melt and retention.

Students who complete both the noncredit and the for-credit modules get a transcripted grade, and students who successfully complete a “Gateway” (normally, three tightly thematically related courses) with a grade of A or B are admitted to the degree. As the pilot program offered only three courses, the first course each in three separate gateways, at this point none of the students are actually admitted into the degree. Many students are on track, and this could change as students’ GPAs rise and lower in the next two courses.

The three courses produced remarkably similar grade curves and student evaluations (an average of 4.5 of 5 on Coursera’s webpage). Counted together, the raw numbers are as follows:

- Fifty-six percent of the students who signed up actually attempted the for-credit coursework (127 of 225). Forty-four percent of the students who signed up for the M.S.-EE realized that the courses were not for them, self-identified and withdrew.

- Of the students who did not withdraw, 78 percent finished the coursework, 75 percent with a C or better. Twenty-two percent were administratively withdrawn because they did not finish.

- Of the students who finished the coursework, 96 percent finished the courses with a C or better, 86 percent achieved grades of A or B, and 4 percent received below a C, one of whom incurred an honor code violation.

- Of the students who finished with a C or better, 97 percent re-enrolled after the pilot for more courses.

Discussion

The most striking result of the pilot concerns the partnership between Coursera and the University of Colorado at Boulder. These two entities collaborated to launch and land three for-credit courses within a larger degree program without a significant error. This included enrolling students, billing, withdrawals, advising, exam scheduling and proctoring, and a host of additional processes, as well as conducting the courses themselves.

The complexity of this task truly fits my governing metaphor: a space shot. I wasn’t privy to the late nights and early mornings at Coursera’s Mountain View offices, but I do know it took a superhuman effort on the part of the department of electrical, computer and energy engineering; the provost’s office; the registrar; bursar; and Office of Information Technology at CU Boulder and the University of Colorado System’s Information Services unit.

Additionally, the courses themselves proved themselves capable of differentiating student performance from A to F according to the faculty’s standards and caught an honor code violation. That is what we ask of our residential programs, and it is what we accomplished here.

The MOOC paradigm has been widely criticized for low completion rates. The M.S.-EE is not a MOOC. It involves fees and credits. Nevertheless, it is based on the MOOC paradigm in both detail and in spirit.

The question remains, “What was the pilot’s completion rate?”

To my mind, counting the original roster of 225 students fails to recognize the way performance-based admissions aggregates processes traditionally considered separate, which are then disaggregated at a fixed census date. Two hundred and twenty-five students signed up, but 44 percent withdrew of their own accord. I would term this 44 percent the program’s melt.

A reasonable argument can be made for defining the completion rate around the central number of 127, those students who attempted the coursework. Of those students, 22 percent had to be administratively withdrawn because they did not finish the coursework, and an additional 3 percent did not achieve a grade of C. This suggests a completion rate of 75 percent with open admissions and a 96 percent passing rate of those who finished the coursework.

I do not believe 75 percent reflects an accurate completion rate. Without an admissions process, the coursework is always operating as a sorting mechanism, always testing the limits of the students’ abilities. One might say that a campus course does exactly the same thing; however, the purpose of graduate admissions is to screen for the best students, ensuring a high completion rate.

If graduate admissions works, every graduate program should have a high completion rate because only nonacademic factors would cause a lack of retention. The purpose of performance-based admissions is equity in access, which this program provided. The performance-based system is not directed at retention at all, but in its way, at the exact opposite: making the standard of retention clear at completion.

Coming to a clear understanding of why students did not complete will demand more data about the students and a redefinition of terms to fit the context of performance-based admissions.

Conclusion

In his recent Inside Higher Ed article “Netflix, Low-Cost Online Master’s Programs and ‘That Will Never Work,’” Joshua Kim argues that the lesson of the media giant Netflix for higher education is an unavoidable transition from “high-priced master’s programs to low-cost master’s degrees offered at scale.”

The notion of the “low-cost master’s degree offered at scale” is now embedded in the discourse surrounding online education. The promise of the “low-cost master’s degree” is that technological adaptation of degree programs to the changing academic market will drive institutions of higher education from their intrinsic elitism toward greater equity in access through temporal and geographical flexibility as well as lower pricing.

For the M.S.-EE pilot, three truths seem evident:

- The program was not crippled by its innovative nature. Although we engaged with multiple new approaches at the same time, the program successfully moved students through graduate-level courses using automated enrollment, performance-based admissions and MOOC-based teaching methods.

- The performance-based system demands careful reconsideration of the concepts of recruitment, application, enrollment, completion and retention. Understanding how students behave in an asynchronous environment unfettered by admissions protocols will take time.

- Those students who completed were largely successful, with 96 percent students getting a grade above a C. The 97 percent re-enrollment of passing students evidences that the performance-based admissions system has produced an identifiable cohort of students. These strong numbers suggest that the students who knew (or discovered) what they were getting into -- graduate-level training in electrical engineering -- could succeed in the MOOC-like environment. Thus, making the M.S.-EE’s challenge clear and figuring out stronger support methods for students who might be able to complete is a very pressing task at hand.

This brings me to some larger thoughts about the nature of a pilot. Netflix, of course, is not merely a distribution channel. It is also a production house, piloting some of the most innovative dramas on TV. It has driven the notion of the TV show from annually based programming featuring synchronous and episodic storylines to complex long-form narratives spanning hundreds of hours, accessible asynchronously, often all in one go. The Netflix lesson, if the comparison holds true, is not simply about modality and cost but about a deep sense of the intertwined nature of form and content.

Netflix, and its ilk from Amazon to Disney, seems to have arrived at a more or less stable economy balancing modality, form and content. Digital education looks less like Netflix today and more like the HBO show Deadwood: a frontier.

As much as our field is chaotic, it is also filled with potential. In order to achieve the promise of the affordable, at-scale degree, to write a new educational economy that allows the brilliance of inspired research and teaching to be accessible regardless of location, gender identity, race, ethnicity, creed or religion, we will need to take bold risks, and as we take those risks, we will also need to return to what we have done, diving deep into the data we possess.

***

Floating among the interwebs, teacher of thousands yet alone, I realized an emptiness foreign to my regular classroom experience, even to my traditional online classroom. Within a week of this realization, I began to receive new transmissions: my students began to reach out to me on my campus and my personal email alike, telling me about how important the course was to them, about childhood reading and adult ambitious, about personal achievements and individual tragedies. In the subsequent weeks, they began to upload their comics, thousands of comics, that revealed an imaginative universe beyond my helmet.

Floating among the interwebs, teacher of thousands yet alone, I realized an emptiness foreign to my regular classroom experience, even to my traditional online classroom. Within a week of this realization, I began to receive new transmissions: my students began to reach out to me on my campus and my personal email alike, telling me about how important the course was to them, about childhood reading and adult ambitious, about personal achievements and individual tragedies. In the subsequent weeks, they began to upload their comics, thousands of comics, that revealed an imaginative universe beyond my helmet.

What I realize now is that I was never Major Tom, never the astronaut in the illustration; I was Ground Control, beaming out a message to many individuals, themselves on individual journeys beyond my control. Learning belonged not to me but to them.

There are many challenges ahead of us as we launch the vehicles of 21st-century education. Some of these challenges will entail changing processes that have been sanctified by time into tradition. Others will demand thinking about educational outcomes fitting a world pressurized by the forces of machine intelligence and the biotechnical alteration of what it means to be human. Some, too, will involve rethinking our roles as teachers.