You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

WASHINGTON – Mark Emmert, president of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, adamantly opposes “pay for play," the idea (favored by many athletes' rights advocates) that college players deserve more compensation because they don't get a fair share of the revenue in big-time sports. And Emmert made clear Monday that a new plan he’s proposing this week to the Division I Board of Directors, which would help close the gap between what a full athletic scholarship covers and the actual cost of attending college by allowing “probably allow up to $2,000” in additional scholarship money for athletes whose conferences permit it, does not signify a shift in that stance -- though he fears critics might say it does.

Increasing the value of an athletic scholarship “to more closely approach the full cost of attendance” is “unequivocally not” pay for play, Emmert said, announcing the plan at a meeting here of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. The scholarship gap ranges from $200 to nearly $11,000 annually, depending on the institution.

But that didn’t assuage the worries of the many college presidents and other members of the Knight Commission, who spoke of financially and philosophically frustrated faculty members, the significant resources and attention already paid to athletes, and the competitive recruiting advantage of the conferences that can afford to offer more money.

“I’ve got 1,400 faculty who would love to have $2,000 more,” said Michael V. Martin, chancellor of Louisiana State University, who spoke after Emmert on a panel of presidents. The resources that flow into many sports programs -- in terms of facilities and gold-plated academic services -- and the elevated social status that sports programs have on many campuses, Martin said, “send a message at times that is not in the best interest of the institution.”

Similarly divisive was the prospect of shifting financial incentives for coaches from bowl game appearances and successful records to high graduation rates and grade point averages. While that’s not part of any formal proposal on the table, it’s an idea that the commission itself has discussed, one member said.

The scholarship plan would also allow institutions to offer multi-year scholarships instead of annual ones, preventing teams from dropping athletes when they get hurt or a hotter, younger recruit comes along.

Spending Disparities

Emmert’s announcement followed the Delta Cost Project's unveiling of yet another gap -- this time between how much athletic programs spend on athletes and how much their institutions spend on students. From 2005 to 2009, athletics spending per athlete at Football Bowl Subdivision colleges grew by 50 percent, to $91,050 per individual, while academic spending per student grew by 22 percent, to $13,470. Institutional subsidies per athlete grew at the fastest rate -- by 53 percent, to about $18,390 in 2009.

At Football Championship Subdivision institutions, rates of spending are lower but institutional subsidies are higher. Athletic spending grew by 42 percent to $35,220, while academic spending grew by 23 percent to $11,780. Institutional funding grew by 34 percent, to $23,000. Total spending was similar at Division I institutions without football, but their rates of increase were smaller.

In a brief mention of conference revenue from television contracts, the researchers also found that the revenue the five biggest conferences will receive through their contracts -- $14 billion total, for the Athletic Coast Conference, the Southeastern Conference, and the Big Ten, Big 12 and Pacific-12 Conferences – is equivalent to the country with the 110th-highest gross domestic product in the United Nations. “It would be a small – but still tangible – country,” they said.

Eligibility Benchmarks

Besides matters related to cost and spending, the other big item on Monday’s docket was the prospect of raising athletic eligibility standards.

The NCAA announced in August that it will up the ante for Division I teams that aren’t on track to graduating enough players. In addition to raising the minimum Academic Progress Rate necessary for a sports team to remain in good NCAA standing from 900 to 930, a benchmark that will be phased in over two years and that the NCAA says indicates at least half of athletes are on track, the association said teams that don’t meet the APR standard will face a ban on postseason play in addition to financial penalties. (Had the APR minimum been 930 last year, Emmert said, seven basketball teams that participated in the 65-team NCAA tournament would have been excluded, including the eventual national champions, the University of Connecticut.) At its two-day meeting at the end of this week, the board will finalize the language of the APR requirement, and formally apply the postseason ban component to football.

The board this week will also nail down the specifics of plans to raise eligibility standards for incoming athletes, an idea that came out of the retreat for Division I university presidents that Emmert hosted in August. The new rule will “probably” entail raising the minimum grade point average requirement, from 2.0 to 2.3, Emmert said, or in the case of transfer students, to 2.5. He also wants to compel high schools to require more robust core curriculums, which students should complete over time, not just a summer or two before they graduate and head to college.

“We are bringing in young men and women who are not prepared for collegiate-level education,” Emmert said. “Their probability of success is limited, to say the least.”

Other ideas that are less far along could give students time to catch up academically once they’re already on campus. At the January board meeting, a proposal to be introduced could reinstate an “academic redshirt model,” which would allow colleges to delay competition for students with athletic scholarships for a year to give them a head start. A similar concept still under development might see universities partnering with community colleges, where new athletes who need remedial work could catch up before starting their athletic eligibility clock.

Integrity and Conduct

Eligibility was one of two major topics of discussion at the presidential retreat; the other was what to do about integrity and conduct issues. “When we got together in August -- and the mood would be no different today -- I and the university presidents were disgusted with much of what we’d seen in the previous year,” Emmert said, alluding to high-profile scandals at places such as Ohio State University and the University of Miami. (The NCAA’s investigation into possible recruiting violations by Auburn University and former quarterback Cam Newton, which just wrapped up last week, began in September 2010 and cleared both of wrongdoing.) The various incidents have been “annoying in the extreme and eroding to all that we agreed about and cared about,” Emmert said.

So the NCAA plans to refine its approach to rules enforcement and “completely change” the infractions structure, in hopes of creating more consistent responses when violations occur, emphasizing the biggest and most egregious infractions “that really affect student integrity and welfare,” such as academic fraud, and getting rid of needless rules. (For instance, Emmert said, the three pages dedicated to appropriate envelope sizes for mailings to recruits are not necessary. Nor is the stipulation that it’s O.K. when courting a prospective athlete to give him or her a bagel because it’s a snack, but add cream cheese and it becomes a meal -- and a violation.)

Emmert said this will all make for a “significant shift” in what the national NCAA office spends its time on. While he didn’t offer a detailed timeline for this restructuring, he said the various proposals won’t go through the normal, tedious NCAA legislative process, which typically takes at least a year to get a proposal to the point where the board can vote on it. Rather, at this time next year, the board will already have decided whether to act on proposals such as minimizing non-conference play, nixing international travel for teams, or redirecting resources away from non-coaching athletic department staff.

Next Steps

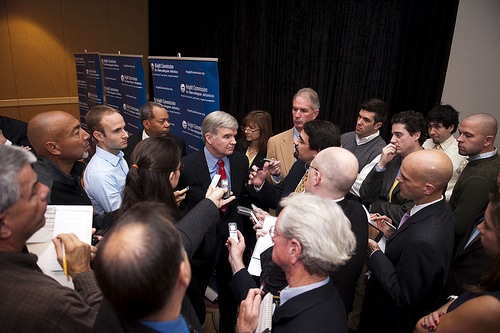

In a media briefing after the meeting, the Knight Commission co-chairs said Emmert’s “reform agenda” champions some recommendations that the group made last June in the latest installment of its “Restoring the Balance” report, such as postseason eligibility requirements. But the chairs stopped short of jumping for joy.

“It’s a good start,” said William E. Kirwan, chancellor of the University of Maryland System, “but we feel it does not go far enough.”

The commission also announced Monday that it will undertake a series of studies and partnerships with independent groups to examine what it says could be the systemic issues diluting the integrity of college sports. This will include athletic spending patterns, conference realignment and the role of university boards of directors, among other things.

During the meeting, Kirwan wasn’t the only one who wanted Emmert to address the “dance going on with various conferences,” the weeks-long saga that saw several institutions abandoning their current conferences -- presumably for more lucrative television contracts. Besides generally causing chaos, the frenzy left some conferences in unstable condition and expanded the geographic reach of others in ways that commission members said could only hurt athletes when they travel for games -- particularly those who play during the week, not just on Saturday.

While Emmert admitted he’s frustrated by the rash realignments – though he acknowledged that he voted for the Pac-10 to expand into the Pac-12 in his past position as University of Washington president -- he played down the role of the NCAA.

“The NCAA does not have a role in conference affiliations, and I agree that the NCAA should never be in the business of telling universities what affiliations they should have,” Emmert said. “When you see all this landscape moving around, you naturally enough want to make sure you’re protecting your university’s interests, and those interests are complicated…. The troubling piece was the lack of thoughtfulness in some cases, the surprised nature of some of it, the lack of good information that many people had in this process, and the cost that it was bringing in collegiality.”