You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The history job market is on the mend, albeit in a very small way, according to a report released Monday by the American Historical Association.

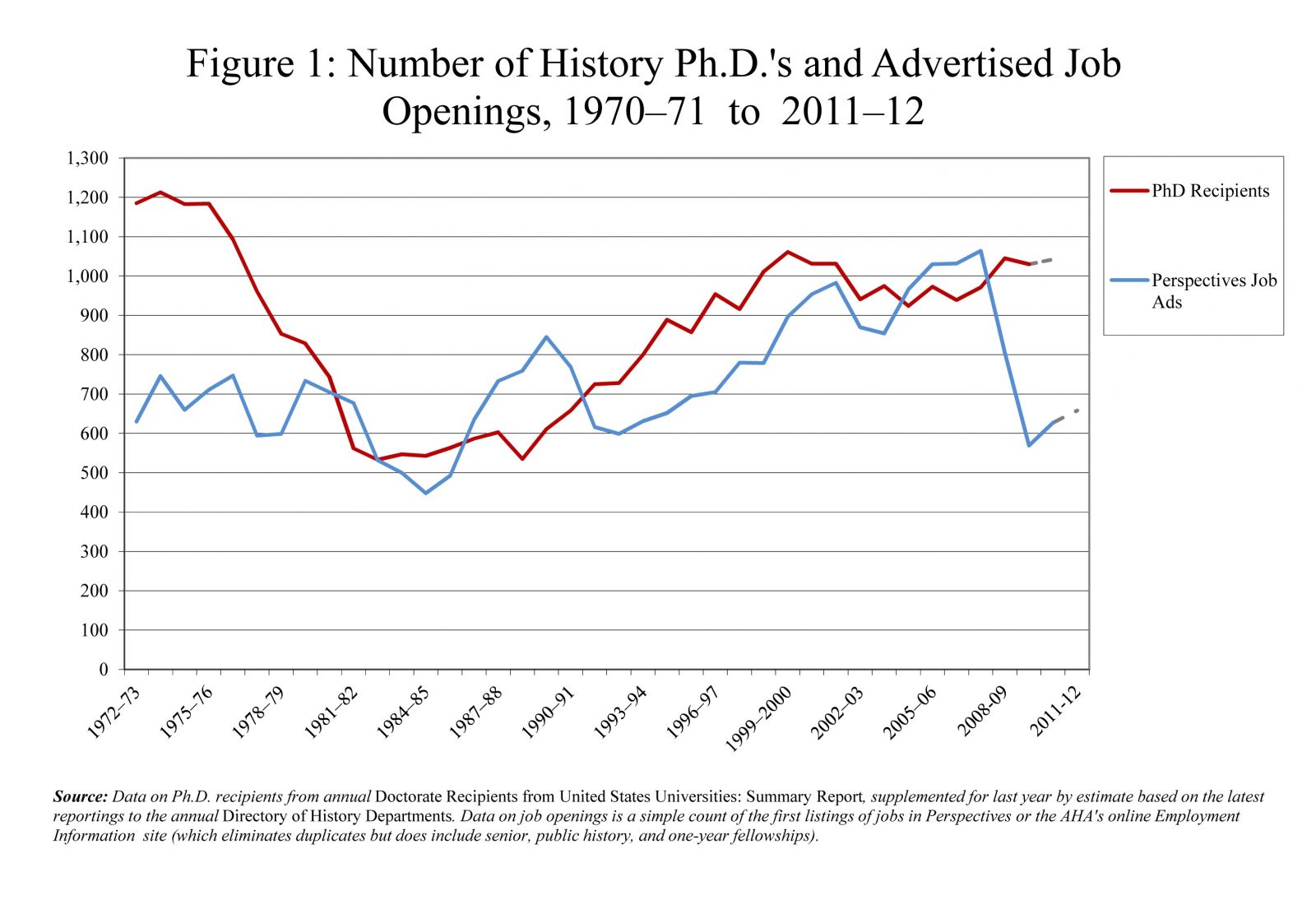

The number of jobs listed with the association in the 2010-11 academic year increased by 10.2 percent over the prior year, from 569 to 627. The gain doesn't suggest a healthy job market, however, because the figures from the previous academic year represented a historic low. And just three years ago, the number of positions listed with the history association was 1,064, the highest it has ever been. (While not all history jobs are listed with the association, the AHA data are considered a reliable measure of the market.)

History continues to lag behind other disciplines when it comes to improvements in the academic job market, according to the report. Adding to the woes in this discipline is the high number of Ph.D. recipients, which was more than a 1,000 last year.

The report, released the same week the American Historical Association holds its annual conference in Chicago, is sure to renew controversy over whether history departments let too many students into their doctoral programs, and the role of professors in failing to encourage graduate students to consider nonacademic careers.

Robert B. Townsend, the author of the report and a deputy director at the AHA, said the small gains at least reverse what he called “a terrifying trend” of the last two years of sharp drop-offs in available jobs. Townsend said the sudden spike of available jobs in the 2007-8 academic year had given many an undue sense of optimism.

“We go through these tense periods when the jobs dry up. There is talk about getting jobs outside academia. And then the jobs come back, we go back to the same old habits,” he said.

He had argued in a column in the December 2011 issue of Perspectives that just looking at the number of graduates and the available jobs was simplistic.

“One of the biggest challenges for students and the departments admitting them is the often dramatic changes that can take place between the time someone starts in a Ph.D. program and the time someone actually finishes,” he said in the article. “So it creates a real challenge for anyone trying to peer into the future and see where things are going, particularly at an individual level. And to the extent history doctoral students are trained to look narrowly only at jobs in colleges and universities, we are further facilitating new crises.”

In the new report, the largest number of jobs advertised was in the subfield of history of North America, with 182 advertised positions. Of all available jobs posted, 69 percent were for tenure or tenure-track positions; that proportion used to be about 75 percent before the recession.

Even though there were more jobs available for those who want to teach the history of North America, the subfield attracted the most applications for junior faculty positions, with an average of about 95 applicants per job opening in 2010-11. In comparison, advertised jobs in the subfields of Africa and Asia attracted an average of 60 applicants per junior faculty position.

Reflecting the oversupply in the entire discipline, each position received an average of 87.3 applications, an increase from the 84.9 applications in the 2008-2009 academic year.

One bright spot: the number of full-time faculty hires surpassed the number of professors leaving history departments for the first time in three years.

The number of new Ph.D.s continues to rise, with a 3.1 percent increase to 912 in the 2010-11 academic year. “While this may seem dubious at a time when the number of academic jobs is near the lowest level in 30 years, it reflects both a long-term trend and the optimism of about eight years ago when many of them first started their graduate program,” the report says.

These rising numbers represent a kind of wishful thinking, said Lawrence Cebula, a history professor at Eastern Washington University, who writes a blog called Northwest History. “It so happens that a lot of historians feel that there is some kind of professional success in sending students to get Ph.D.s. They tend to brag about them,” Cebula said.

The professor, who said he openly discourages his students from pursuing academic careers, has been at the forefront of a debate this year because he wrote a blog post called “Open Letter to My Students: No, You Cannot be a Professor," in which he encouraged history students to look beyond a career in academe. The blog post touched a nerve, and by the end of the year it had received 40,000 hits, Cebula said.

He likened the effort to get a Ph.D. in history and then find an academic job to “someone buying a lottery ticket with nine years of their life.”

His arguments mirror what the AHA itself said in October 2011, when the organization’s executive director and president said that the academic job market wasn’t going to make a comeback soon and Ph.D. programs needed to change to accommodate options beyond academe.

“We tell students that there are ‘alternatives’ to academic careers. We warn them to develop a ‘Plan B’ in case they do not find a teaching post. And the very words in which we couch this useful advice make clear how much we hope they will not have to follow it – and suggest, to many of them, that if they do have to settle for employment outside the academy, they should crawl off home and gnaw their arms off,” said Anthony Grafton, president of the AHA and a Princeton University professor, and James Grossman, who is the executive director of the association.