You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A seat on a private university board comes with a lot of authority. Trustees hire presidents, approve budgets, often have final say on academic programs, and are increasingly vested with the responsibility of determining how to invest giant sums of money.

But giant sums of money tend to mean giant questions.

Maintaining strong returns on university investments has become pivotal to the long-term health of many colleges and universities. As a result, individuals with experience and connections in financial management have become common on governing boards. But having people on the board who have connections to the financial world raises the possibility of conflicts of interest – board members privately benefiting by placing the college’s investments in their own firms.

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis – when colleges with endowments greater than $1 billion lost an average of 20.5 percent, leading to significant cuts and the disruption of local economies – employees, students, and community members have begun to criticize the high-risk strategy endowment managers adopted over the past few decades. They have also questioned whether those managers are making investments with their institutions’ best interests in mind, highlighting instances where trustees invested an institution’s money with firms in which they had a personal financial stake.

There have been several instances of groups alleging that board members acted illegally or unethically, the most recent example being an allegation, under review by the New Hampshire attorney general, that surfaced last month at Dartmouth College that the board was steering the college’s $3.4-billion endowment to its members’ firms.

“Dartmouth’s situation is indicative of more widespread trends in the composition of college and university boards, where pride of place (and often majority rule) is given to trustees from business backgrounds, with a disproportionate percentage working in finance and increasingly in the alternative asset management industry that plays such a pivotal role in the Endowment Model of Investing,” wrote the Center for Social Philanthropy at the Tellus Institute, a Boston-based think tank focused on sustainability, in a 2010 report that sparked discussion about conflicts.

Defenders of the system argue that colleges have sufficient safeguards in place to prevent conflicts of interest and that having experienced financial managers on boards, who can provide advice and potentially favorable terms on investments, is vital to these institutions’ long-term success.

The debates raise questions about whether colleges should be allowed to engage in business with board members’ firms, whether the current slate of disclosure laws are enough to allow for the identification of potential abuses, and whether the formal rules and social norms that govern financial decisions do enough to properly discourage potential abuses.

The Dartmouth Case

In February, the New Hampshire Attorney General received a letter from a group called “The Friends of Eleazar Wheelock” (Dartmouth’s founder), that identified itself as “a group of former and current faculty, staff, and employees of Dartmouth College.” The group gave no other indication of its members’ identities or how many people it included.

The letter alleges that members of the college’s board and investment committee have funneled the college’s endowment to hedge fund, private equity, and venture capital firms they manage. The letter alleges that board members have not been forthright about these investments and the fees paid to their firms. The letter provides a list of investments the college made and how these investments relate to trustees. It alleges that the trustees violated state law and calls for the trustees to step down.

A representative from the Charitable Trusts Unit of the Attorney General’s office said the unit is looking into the letter’s allegations.

Dartmouth, through Justin Anderson, the assistant vice president for media relations, denied any wrongdoing. Anderson said the allegations in the letter are false and that the college will soon file a response with the Attorney General’s office. But that does not mean Dartmouth is denying significant investments through firms with links to its trustees.

Like many states, New Hampshire prohibits transactions between charitable trusts and firms with which a trustee, director, or officer has a direct or indirect financial interest unless that transaction “is in the best interest of the charitable trust” and the board meets certain conditions. In New Hampshire, these conditions require that the transaction be fair to the trust, that at least two-thirds of the disinterested board members approve it, that interested parties are not present during the vote, that minutes are kept, and that the board publishes a notice of the transaction in a “newspaper of general circulation in the community in which the charitable trust’s principal New Hampshire office is located.”

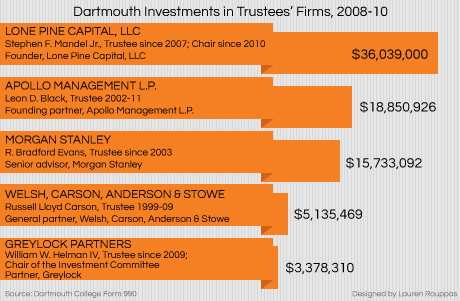

Dartmouth is open about the fact that it engaged in transactions with firms in which its board members had some interest. According to Internal Revenue Service forms, between July 1, 2008 and June 30, 2010, the two most recent years for which information is available, the college made $36 million in capital contributions to funds run by Lone Pine Capital LLC, a privately owned hedge fund sponsor founded by Stephen F. Mandel Jr., chairman of the Dartmouth board, and almost $19 million in capital contributions to funds run by Apollo Management L.P., a private equity group founded by then-trustee Leon D. Black. The college also conducted several other transactions with firms run by trustees (see graphic).

Anderson said the college complied with all state and federal restrictions and reporting conditions each time it made a related-party transaction. The college also followed its own conflict of interest regulations, which require a comparison of a related-party fund’s past performance and terms to similar firms'. The investment must also not comprise more than 10 percent of the college’s overall investments.

Independent groups, including think tanks and student groups, found records of disclosures in The Valley News, a newspaper based in Lebanon, New Hampshire, and the paper of general circulation for Hanover, where Dartmouth is located. The paper has a daily circulation of 18,000, and Joshua Humphreys, a fellow with the Tellus Institute who found several of the notices, said they were not very large. The paper also does not have an online archive of such notices, meaning that any person interested in the college's investments would have to review the paper's physical archives. So despite Dartmouth's national prominence, the notices did not reach a very large number of readers.

Critics have long highlighted transactions between colleges and universities and companies where their board members have some financial interest. But many argue that relationships in the investment world are different. The difference between a construction contract and a hedge fund investment could be several orders of magnitude.

Dartmouth is not alone in facing this criticism. An investigation by Reuters in May noted that Brown University invested in firms with ties to at least half a dozen trustees. Reuters found that other wealthy colleges including the Ivy League institutions, the University of Chicago, and Stanford University, also engaged in transactions with board members’ firms. All of the information collected by Reuters was self-reported by the universities on IRS forms. The institutions Reuters spoke with said they had adequate safeguards in place to prevent conflicts of interest.

Anderson said the investments Dartmouth made in firms where a board member had some financial interest were determined to be the best investment options for the college, and therefore in the best interest of the college. “To forgo investments with a firm simply because a board member has some interest in the firm would be contrary to the best interest of the college,” he said.

Anderson said, but was not able to provide data on deadline to prove, that the investments in related-party firms outperformed the rest of the college’s portfolio, which Anderson takes as proof that the decisions truly were in the college’s best interest and that the decisions were based on merit, rather than some personal connections.

Are There Enough Safeguards?

Critics say the current slate of disclosure requirements do not go far enough. For example, the IRS Form 990 requires institutions to disclose transactions involving board members, but most colleges do not go into as much detail as some interested parties would like. One entry from Dartmouth’s 2009-10 Form 990 lists a $3,503,358 “capital contribution” with “Apollo Investment Fund VI,” and that the interested party is a “Dartmouth Trustee and Apollo Management Officer.” But the listing, like most of the form, does not list the name of the interested person or any details about the transaction’s terms.

Each form also only lists transactions for that fiscal year. If a person wanted to get a full picture of a college’s investments with a specific firm, he or she would have to aggregate many years of transactions. State reporting requirements are similarly limited.

Humphreys, a fellow with the Tellus Institute and the lead author of the 2010 report, said more needs to be disclosed, including the aggregate amount the college has invested in a particular firm and the nature of the investment, such as what the fund is and what fees are charged. The firms in which institutions are investing their endowments, such as hedge funds and private equity groups, often have fewer disclosure requirements than traditional investments. For that reason, the public is generally in the dark about exactly what a college’s money is being invested in and how specific investments are faring. As a result the public is generally incapable of making independent judgments about the wisdom of particular investments.

“Taxpayers are subsidizing these investments,” Humphreys said, referring to the tax-exempt status of non-profit institution endowments. “We should know what we are subsidizing.”

In a report released in April, in which the Tellus Institute looked at the reporting of conflicts of interests by the 20 wealthiest private colleges in Massachusetts on both federal and state forms, the institute said the current system of transparency does not work. “86 percent of the schools reporting potential trustee conflicts in this study provide disclosures of business transactions with related parties that appear in some measure erroneous, problematic or substantially incomplete,” the report states.

Several Massachusetts lawmakers and the Massachusetts chapter of the Service Employees International Union, which represents staff in many of the state’s private and public universities, have pushed a bill in the state legislature that would require greater disclosure of university investments.

While increased reporting requirements might assuage some critics, they won’t mollify all of them.

Even if the transactions are in colleges’ best interests, and even if each college followed proper reporting procedures each time it engaged in such a transaction, many critics say that’s not sufficient. Investments such as the ones Dartmouth are making create the appearance of impropriety, many argue, and there’s no way to eliminate such questions other than refraining from such transactions.

Richard P. Chait, a faculty member at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education who studies institutional governance, has said repeatedly that the only way colleges and universities can truly avoid allegations of corruption and mismanagement is to almost always avoid doing business with trustees’ companies.