You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In the days when few colleges even imagined a woman as their leader, there was one corner of academe where women ruled: Roman Catholic colleges.

Until the late 20th century, a Catholic college president was more likely than not to lead a women's college, and to do so in wimple and veil rather than suit and tie. But as women have risen to the top job at more colleges overall, they’ve lost ground in Catholic higher education, their ranks dwindling as colleges went coed and lay leaders replaced nuns. The number of women in the presidency at Catholic colleges is now at an all-time low.

In a church recently roiled by conflict over gender, some are worried that a bastion of female leadership is endangered. “Since the beginnings of Catholic higher education, women, and in particular women religious, have played a substantial and substantive role in leadership,” said Michael Galligan-Stierle, president of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities.

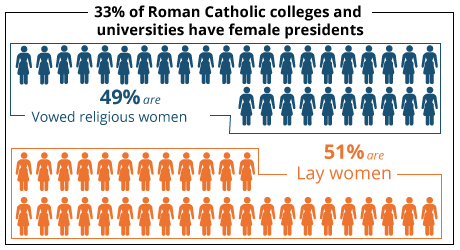

In 2003, when 36 percent of Catholic college presidents were women, the association put it in stark terms: “Women are disappearing from the presidency." Since then, at least eight colleges with a tradition of women as presidents have hired their first men for the post. The proportion of women has dropped to 33 percent.

Women who lead Catholic colleges caution that reversing the trend could be difficult. Nationwide, women who are college presidents are still outnumbered 3 to 1 by men. Lay presidents, men or women, must negotiate between church doctrine and academic traditions. Then there’s the matter of the male-dominated church hierarchy.

“They are theologically and intellectually more complicated than a secular institution,” said Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University, a Catholic women’s college, adding wryly: “I would not look to Catholic colleges to be the trend-setters on gender equity."

Catholic colleges still have a greater proportion of women serving as presidents than higher education as a whole. Slightly more than a quarter of college presidents nationwide are women.

Some argue that as Catholic colleges continue to choose lay leaders, the gender makeup of the presidency will start to look more like non-Catholic colleges.

“For better or worse, is this a painful right-sizing?” said Donna Carroll, the first lay president of Dominican University in Illinois, suggesting that women’s representation in Catholic presidencies might be “tracking to the mean” of colleges nationwide.

The majority of Catholic colleges were founded by women’s religious orders, and they were led by members of those orders for decades. In the late 1960s, when only a handful of women led non-Catholic colleges, almost two-thirds of Catholic college presidents were women.

Then came two waves of historic change. Catholic women's colleges started admitting men, and the number of Catholics entering religious orders dropped precipitously. Leaders of the newly coed colleges were more likely to be lay Catholics. Especially in the 1970s, they were more likely to be male. And once colleges began picking men as presidents, they often continued to do so -- even as women gained substantial experience in college administration and rose to the presidency elsewhere.

That’s true even at colleges historically led by women that first hired male presidents decades ago. Several that did so early on -- including the College of St. Scholastica, which appointed its first in 1971; Mercyhurst University, in 1972; and Viterbo University, where a Catholic priest was the first man to be president, in 1970, and was succeeded by a layman -- haven’t hired a female president in 40 years, since the last nun presidents retired.

Catholic colleges that hired their first lay leaders more recently were more likely to choose women than in the past. When Carroll became the first lay president of Dominican University in 1994, all three final candidates for the job were women, she said. “I think there was a strong hope that it would be a woman,” she said, adding that she expected some on the board hoped they would find another member of a religious order.

Many men are still hired to replace nuns. Notre Dame of Maryland, a women’s college, made news in February when it selected a man as its second lay president. And members of religious orders -- who make up about half of the women serving as Catholic college presidents -- have an average age of 65. As they continue to retire, the number of women in the presidency is likely to continue falling.

Fund-Raising Is Key

Almost all Catholic colleges are dependent on tuition, not endowments, for revenue. Many were on rocky financial ground even before the economic downturn. Search consultants say fund-raising ability and business acumen, not just academic administrative experience, are now driving factors in presidential searches.

“Women aren’t always as well-developed in those areas,” said Kim Morrisson, a managing director and practice leader for education searches at Diversified Search who has placed both men and women at Catholic colleges with historically female leadership. “That’s a challenge, but not by any means insurmountable.”

When McGuire became president of Trinity Washington in 1989, she was the college’s second lay president. (The first, a man, lasted less than two years; McGuire, who served on the search committee that selected him, said she doesn't recall any women under serious consideration.) She was an experienced fund-raiser, a member of the Trinity board, and an assistant dean at Georgetown Law, but even so says she doubted the board would hire someone with her credentials today.

“Many of these places are financially very fragile,” McGuire said. “Quite often, when the boards go out to find their first or second or third lay president, they’re looking for business savvy. I hate to say it, but in our world, that immediately comes with a coat and tie.”

That obstacle, and others, are common in higher education as a whole, said Judith White, president and executive director of the Higher Education Resource Service, which promotes female leadership in higher education. Women are more likely to slow down their careers when they have children. They can also face cultural biases and stereotypes about leadership. Boards say they want a president who’s willing to collaborate and negotiate, White said, but women who have those qualities are often asked to prove instead that they’re tough and authoritative.

But those challenges aren't insurmountable. The ranks of women in the presidency -- as well as top administrators, including many in business positions -- continue to grow. Women now lead half of the Ivy League, including universities that didn't admit women as students until the 1970s. In contrast, no Catholic college that began as a men's institution has a woman as president.

Theology and Hierarchy

Since women are still underrepresented in presidencies overall, women with administrative or fund-raising experience are in high demand in presidential searches. The competition means that non-Catholic colleges might make offers that are financially more appealing -- or just less complicated.

Presidents at Catholic colleges deal with tough questions, balancing academic freedom with church doctrine, the passionate beliefs of faculty with those of the local bishop. Subjects that pass unremarked on secular campuses seem perpetually up for debate: Commencement speakers. Policies on gay students. Student theatrical performances. And, most recently and explosively, contraception.

Those tensions have flared recently, in the dispute over whether Catholic institutions should be required to offer health insurance covering birth control, as well as in the Vatican’s condemnation of American nuns for challenging bishops on homosexuality and the role of women in the church.

So far, no Catholic colleges with women as presidents have joined lawsuits over the birth control mandate. Those who spoke out publicly, including McGuire, generally urged inclusiveness and compromise. "Everyone wants to be supportive of the church, but there are different ways to do that," she said.

But Catholic college identity doesn't only offer complications, McGuire and Carroll said. The benefits include a sense of mission and vision, a shared commitment to education and social justice, and the opportunity to talk about religion and values in daily life. Carroll, the president of Dominican, said she feels a sense of vocation -- a religious calling -- even though she isn't a nun. "If you believe deeply in the mission of the place, and you see the outcomes of that mission in the experience of students, it's a very rewarding job to have," she said.

For a woman hoping to be president, the church ties could be a draw, said McGuire, who credits Trinity's Catholic identity with inspiring its mission of serving low-income students and says she enjoys being "value-centered and faith-driven." But other candidates may decide they don't want to deal with the added complications.

“For some, it may just be another level of complexity," she said. "I can imagine that some folks might say, ‘I could go to XYZ College up the street and not have to answer all those questions.’ ”

Stained-Glass Ceiling?

Women's religious orders founded the majority of Catholic colleges in the country. But the best-known colleges -- including the top Catholic research universities -- were founded by men. At those colleges, with no tradition of women in leadership, presidencies the presidencies are overwhelmingly held by men.

Of the nine universities the Carnegie Foundation considers to have "very high" or "high" research activity, all were founded by men. None has a woman as president. (Four of the 11 Carnegie doctoral/research universities have women as presidents.)

Colleges established by male orders are hiring an increasing number of lay presidents: Georgetown University, founded by Jesuits, hired its first layman as president in 2001; seven other Jesuit colleges have followed suit. So far, none of the lay leaders have been women. At those colleges, the “men’s club” atmosphere can be hard to break through, said Susan Ross, the chair of the theology department at Loyola University Chicago who has written critically on the treatment of women on the faculty at Jesuit colleges.

“It tends to be a kind of male culture,” Ross said of Loyola, adding that the situation has improved in the past decade. “I think it still remains a very difficult place for women to move up the ladder.”

Galligan-Stierle, president of the Catholic college association, said the group intends to reach out to women individually before its conference next year and invite them to a program for aspiring presidents. “Special efforts will be made to invite senior executive women,” he said. “I think higher education, and our church and society, is at its best when we have the expertise of both women and men leading our institutions.”

McGuire said that might not be enough.

“To get the best talent, you have to say out loud that you want women,” she said. “You have to actually hang out the want ad, put out the shingle, open the door, turn on the lights, say, ‘This is something that we do want! Here’s the reasons why you would so enjoy being at a Trinity -- or a Georgetown.' ”