You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

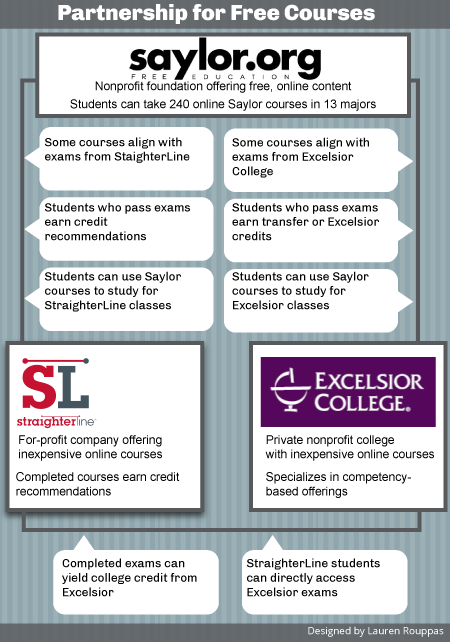

The Saylor Foundation has nearly finished creating a full suite of free, online courses in a dozen popular undergraduate majors. And the foundation is now offering a path to college credit for its offerings by partnering with two nontraditional players in higher education – Excelsior College and StraighterLine.

The project started three years ago, when the foundation began hiring faculty members on a contract basis to build courses within their subject areas. The professors scoured the web for free Open Education Resources (OER), but also created video lectures and tests.

“I was able to develop my own material,” said Kevin Moquin, who created a business law course for Saylor. A former adjunct professor for a technical college and a for-profit institution, Moquin said the foundation gave him the “flexibility to adjust it as I needed.”

Saylor also tapped its pool of contract faculty members to conduct three-member peer reviews of each course, a process which professors described as rigorous. They checked the relevance and freshness of content, and they worked to ensure that all exams are tied to specific learning requirements, or outcomes.

The foundation currently has more than 240 courses up on its website. They are self-paced and automated, and designed to cover all the requirements of an undergraduate major in disciplines ranging from chemistry and computer science to art history and English literature, as well as a general education major. The course material is roughly 95 percent complete, Saylor officials said, and should be finished this fall.

Students have already started taking the classes, and can earn non-credit-bearing certificates. But thanks to newly forged agreements with Excelsior and StraighterLine, the foundation now provides an indirect route to college credit.

Excelsior is a private, nonprofit college that offers relatively inexpensive, online degree programs. The regionally accredited college is also one of the first to have competency-based programs, where students can take Excelsior-developed examinations in a fairly broad range of subjects – earning credits without having to take classes. The exams are worth three to six credits, and typically cost $95.

The college discovered Saylor when it was tracking down open-education material online to suggest for students to use as study guides for exams. John Ebersole, Excelsior’s president, said faculty members at the college were impressed with Saylor’s courses.

“We found ourselves at Saylor’s door,” Ebersole said, adding that the foundation “doesn’t get the cachet, but they have the quality.”

Price Wars?

StraighterLine has a similar partnership in place with Saylor, and, as of this week, with Excelsior. As a result, the group has created what is perhaps the lowest-cost set of credit-bearing courses on the Internet.

Like Excelsior, StraighterLine offers inexpensive courses online. Students pay $99 per month to enroll, shelling out $39 per course. The material is self-paced, and students can take final exams whenever they’re ready. Tutors are available to help them along the way.

StraighterLine differs from Excelsior in that it is not an accredited institution. When completed, the company’s 35 entry-level courses come with credit recommendations that are endorsed by the American Council on Education (ACE), but not credits. Many colleges have agreed to honor the council’s recommendations, although students need to enroll at one of those colleges to get credits for StraighterLine courses.

However, StraighterLine students can now take Excelsior exams that match up with the company’s course material, and are available on StraighterLine’s website. If they pass (Excelsior exams don’t offer partial credit), students earn credits from Excelsior as well as StraighterLine credit recommendations.

To complete the triangle, StraighterLine in May announced that several Saylor courses now match up with the company’s exams. That means a student could earn StraighterLine credit recommendations by passing an assessment after they complete a free Saylor course, spending $99 to sign up for StraighterLine.

The new credit pathway between the three institutions is obviously a tad complex, and not as simple as just enrolling in an online college. But the price might be attractive to savvy adult students – already the typical Excelsior and StraighterLine student. And Saylor hopes to be an option for students, including those in developing countries, who lack affordable or quality education options.

“Online courses should be really inexpensive,” says Burck Smith, StraighterLine’s CEO. “There’s no overhead. There is no reason for costs to be what they are.”

Saylor’s leaders insist the foundation is not challenging traditional colleges, and they sound earnest about their goal of expanding higher education’s reach. The foundation does not plan to seek accreditation.

But Saylor’s guiding ethos – that education should be free – does conflict with higher education’s current business model. Some students who take free Saylor courses might have paid for similar online content from an accredited college. And Smith and others claim that free online content, such as from Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), undermines the pricing model of traditional, fee-based courses.

For now, however, Saylor is just getting started and probably doesn’t pose a threat to any college.

Preventing 'Link Rot'

The foundation is the brainchild of Michael J. Saylor, an Internet entrepreneur who has had several brushes with techie fame. The founder of MicroStrategy, a Beltway-based business intelligence software company, Saylor once lost $6 billion in personal wealth amid a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission inquiry. At the time, he promised to donate $100 million to create a free online university.

That idea grew into the Saylor Foundation, which has a long-term goal of putting a lot of quality academic content on the web – as much as possible, really.

This fall will be Saylor’s launch, for all practical purposes. Although the foundation has gotten some notice among higher-education reformers, the fleshed-out majors make the concept tangible. Based in a sleek but noisy office in the Washington's ritzy Georgetown neighborhood, the foundation’s 20- and 30-something employees are working with faculty members to put the finishing touches on courses.

Angela Bowie is one of those faculty members. Based in Philadelphia, Bowie has worked as a lobbyist and teaches political science and history, mostly at community colleges or regional public universities. She saw a job ad for Saylor, and tossed her hat in the ring. Bowie said the foundation put her through the wringer, asking for information on every course she’d taught over the last decade.

“They did a very thorough vetting,” Bowie said. “More than any other college I’ve ever worked for.”

Saylor has a training program for faculty members, which Bowie also described as thorough. In particular, she praised the foundation’s focus on learning outcomes. Saylor's faculty are paid on an hourly basis, a foundation official said. And Saylor is a side gig for most, who work as professors or adjuncts at traditional universities.

Bowie has designed Saylor courses, including one on Congressional politics. She has worked as a peer reviewer for courses designed by others, and also run peer reviews. In those cases Bowie pulls together feedback from all three reviewers and then assigns it to another faculty member to make changes to the content. The goal of the process is to make sure courses are “pedagogically sound, engaging, and overall sufficient for use by students,” she said.

The content must also be fresh. Dead links, for example, are a no-no. Bowie said she learned a new term for that problem from her Saylor colleagues: “link rot.”

She is optimistic Saylor can make good on its ambitions, and will attract plenty of students who will be satisfied with both the content’s rigor and price, or lack of a price.

Moquin agrees, saying Saylor has huge potential. “I feel excited because I feel that I’m at the beginning.”

Saylor, Excelsior and StraighterLine are natural partners, Ebersole said, because they share the same end goal. That is to make higher education “more of a buffet and less of a fixed meal.”

But the buffet approach only works if it includes a path to a credential, he said, “and ultimately that credential has to mean something.”