You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The underrepresentation and relative academic underperformance of black men in higher education are matters of increasing concern to campus leaders and policy makers. Yet often lost in the shuffle -- except when they are explicitly reminded of it -- is the fact that there is one place where black men are most decidedly not underrepresented on many campuses: on their sports teams, particularly the most visible ones of football and men's basketball.

A study being released today aims very much to drive that point home, since many college officials seem inclined not to notice, says Shaun R. Harper, director of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education and lead author of the study, "Black Male Student-Athletes and Racial Inequities in NCAA Division I College Sports."

"We hear over and over again that colleges and universities just cannot find qualified, college-ready black men to come to their institutions," says Harper. "But it seems that they can find them when they want the black men to generate revenue for them."

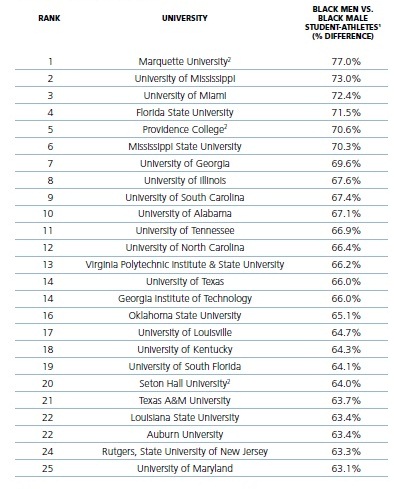

The study by Harper and his co-authors, Collin D. Williams Jr. and Horatio W. Blackman, research assistants at the Penn center, has two main goals. First, it explores the extent to which black men are represented in athletics and among all students at the universities that play sports at the highest level of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (the six conferences that make up the Bowl Championship Series), highlighting those with the biggest gaps in representation (seen in the table at bottom). Over all, black men made up 2.8 percent of full-time, degree-seeking undergraduate students at the 76 institutions, but 57.1 percent of football team members and 64.3 percent of male basketball players.

The study in no way seeks to suggest that there are too many black athletes, Harper says. But at colleges where many of the black students on campus are athletes (a 2008 article in Inside Higher Ed, for instance, identified dozens of institutions in Division I where a third of the black undergraduate men on campus were athletes, and some where more than half were), "black men who are not student-athletes, because they are so few in number, end up suffering from the stereotypes that attach to athletes," Harper says. "It's not uncommon for a black man to get congratulated for a football victory while walking across campus on a Monday morning, despite the fact that he's 5-foot-6 and skinny."

25 BCS Universities With Biggest Gaps in Black Male Representation (All Undergraduates vs. Football/Basketball Players)

(Note: Marquette, Providence and Seton Hall do not play Division I football.)

"We are convinced that if admissions officers expended as much effort as coaches" in scouting, partnering with high schools, and searching "far and wide for the most talented prospects," the report states, "they would successfully recruit more black male students who are not athletes."

College officials often bristle at the suggestion that numbers such as these suggest that they care more about offering educational opportunity to black male athletes than to other black men, and insist that what's really important is how well they educate all the black men (athletes or not) that they enroll.

That explains the second part of the Penn study, which analyzes how successful the institutions are at graduating black male athletes and other black men on their campuses, drawing attention to those with the biggest and smallest gaps in performance.

For each of the 76 institutions, Harper and his co-authors compare the six-year graduation rate for four entering classes of black football and men's basketball players (those of 2001-2004) with the rates for all athletes, all undergraduates, and other black undergraduates. Black male athletes equal or outperform their black male peers at 22 campuses (by more than 20 percentage points at Kansas State University and the University of Cincinnati, for instance), but lag (in some cases badly) at the rest, as seen in the table below. (The same gaps, by and large, do not hold for female black athletes, the study notes.)

BCS Universities With 15+% Gaps in Graduation Between Black Male Athletes and Other Black Male Undergraduates

| Graduation Rate for Black Football and Men's Basketball Players | Graduation Rate for Black Male Undergraduates | Difference in Rates | |

| Clemson U. | 39% | 55% | -16 |

| Florida State U. | 34% | 63% | -29 |

| Iowa State U. | 30% | 47% | -17 |

| Marquette U. | 40% | 58% | -18 |

| Providence College | 40% | 70% | -30 |

| Stanford U. | 68% | 88% | -20 |

| Texas A&M U. | 38% | 55% | -17 |

| U. of California at Berkeley | 40% | 63% | -23 |

| U. of California at Los Angeles | 46% | 66% | -20 |

| U. of Florida | 34% | 64% | -30 |

| U. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | 51% | 67% | -16 |

| U. of South Carolina | 40% | 55% | -15 |

| U. of Southern California | 43% | 72% | -29 |

| U. of Texas at Austin | 43% | 60% | -17 |

| U. of Virginia | 56% | 77% | -21 |

The graduation rates for football and men's basketball players at the institutions skew low, officials at these institutions historically argue, because some of the players leave early to play sports professionally.

And while that's certainly true, Harper notes, athletes benefit from both financial support (in the form of full scholarships) and academic support (in terms of the increasing tutoring and other resources that many Division I colleges have made available to athletes as pressure on them to graduate their players has intensified) that other black male undergraduates may not.

Yet for all the extra support they receive (which he wishes that institutions would make available in equal measure to black non-athletes), Harper argues that black male athletes still are deterred in many cases from taking full advantage of the educational opportunities their universities so proudly boast of giving them. Coaches, he says, frequently discourage players from pursuing rigorous fields of study (scientific disciplines that will require three-hour labs that conflict with practice, etc.) and their intensive time commitments often preclude them from participating in the sorts of academic and extracurricular activities (first-year experiences, study abroad, etc.) that are known to strengthen academic engagement.

Officials at institutions highlighted in the Penn report (such as the few, like Florida State University, that appear on both of the lists above) caution against reading too much into the numbers, given that they represent a snapshot in time, and say that they are working hard both to bolster the academic success of their athletes and to increase their enrollment of minority non-athletes.

"At Florida State University, we strive to be one of the most student-centered universities in the country and every decision is made to serve students' best interests," Karen Laughlin, dean of undergraduate studies there, said in an e-mailed statement. "In the years since this data was compiled, our athletics Academic Support Program has been doubled in size and scope, and our innovative programs to recruit black students into the general student body have received national recognition. Two of our recent Rhodes Scholars were black male student-athletes, one in football and one on the U.S. Olympic team in shotput."