You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

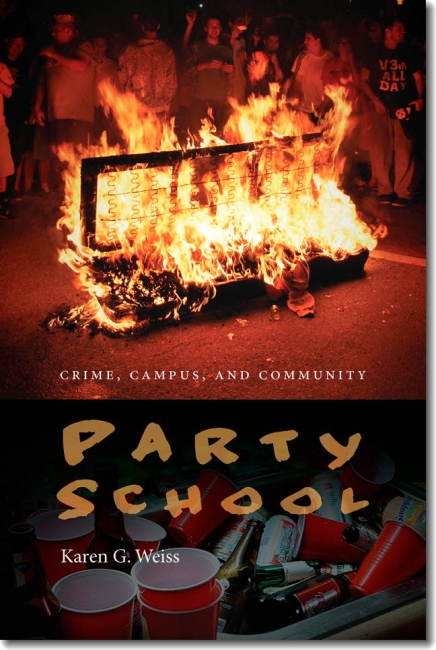

Northeastern University Press

When the Princeton Review sees fit to rank the top “party schools” every year, you know the label has become ubiquitous. And while such rankings might come in handy for the many students choosing their four-year residential university based more on the abundance of liquor than learning, the party school status bears serious consequences for everyone who lives it. In her new book Party School: Crime, Campus and Community (Northeastern University Press), Karen G. Weiss, an associate professor of sociology at West Virginia University, details the extensive and toxic party culture on these campuses and explains how and why it’s allowed to exist.

Weiss blames not just the students who feel entitled to get wasted and steal street signs, or who explain away drunken sexual assaults as just “stuff that happens,” but also the administrators who fail to do anything significant about it. While Weiss sets this case study at “Party University” and the surrounding locale – whose characteristics align exactly with WVU and Morgantown, WV., though the author declined to comment – its contents are representative of many large, sports-oriented residential universities located in geographically isolated college towns. In an email interview, Weiss explained the origins, implications and future of what she terms the “party subculture,” and speculated about ways to combat it.

Q: Let's start at the end. You talk in the book about administrators' ambivalence to the party subculture, but admit in the "sobering" conclusion that most of their efforts to combat it (dry events or campuses, cracking down on parties, or employing a social norms approach) have proved largely fruitless. The change, you say, has to come from students themselves; they have to believe in the negative repercussions of such a culture. So is it hopeless?

A: I wouldn’t say hopeless, but I admit that I am not particularly optimistic about a change, at least in the immediate future. Many residential universities, such as the so-called party schools that I focus on in the book, have become so well-known for their super-charged party environments that it would be very difficult to change the culture without negatively impacting enrollments that are now dependent upon the lure of this party scene. Moreover, many of the disruptive behaviors that I document in the book (e.g., burning couches, riots) have become “traditions” for both current students and alumni. As such, traditions are very difficult to change.

Q: How and why has the culture at party schools become more extreme over the years?

A: Even as some students at most residential universities and colleges have always partied in extreme ways, I argue in the book that an extreme party lifestyle has become more pervasive at the so-called party school due to a disproportionate number of students who come to these schools not to study but to party. When students are more committed to the party scene than to their academic obligations, they are less concerned about how their behaviors impact their own lives. But another problem in recent years is the diffusion of this party subculture into surrounding neighborhoods, due in large part to explosive enrollments and shortages of student housing. This has meant that extreme partying and the bad behaviors that go along with it are no longer contained in student “ghettos” but are impacting many other areas of the college community.

Q: What, in your personal opinion, is the worst result or effect of the party school subculture, either on the campus or community?

A: I am most concerned about the ripple effects of the party subculture in the broader college community. In the book, I liken it to the problems that people living in certain neighborhoods begin to experience after gangs move into their communities. They feel terrorized, they change their routines to avoid certain streets, they don’t leave their homes at night. In many college towns, residents are beginning to experience similar problems (albeit less life-threatening) as a result of a minority of extreme partiers who make life uninhabitable for their neighbors.

Q: "Similar to neighborhoods overrun by gangs, the party subculture claims domain over PU's downtown neighborhoods, holding its residents hostage at night." The analogy in this quote is striking, but you also detail other ways in which the "entitled" party culture holds people hostage: students feeling too afraid or complacent to call out partiers for inappropriate or even illegal behavior, for example, or students skipping football games to avoid "wasted" spectators in the student section. We certainly talk a lot about the health and academic consequences for students who drink, but do you think the "secondhand harms to campus and community," as you term them, are an overlooked effect of the party culture?

A: The secondhand effects of the party subculture are certainly the most profound problems that negatively affect non-partying students and non-student residents of college towns. As described in the book, these harms are similar to problems from secondhand smoke that can impact anyone who spends enough of their time around persons who smoke. A lot of research looks at firsthand injuries and illnesses from drinking and drug use, but far fewer studies look at the ripple effects of substance use on other people. What is especially important about shifting the focus of college partying to secondhand harms is that it makes it harder to rationalize students’ bad behavior while intoxicated as normal or just kids being kids. Instead, it becomes a debate about the rights of students to party versus the rights of everyone else living and working in the college community to live a peaceful existence. It is easy to forget that there are a lot of people at these schools, including many students, who do not party or who do so responsibly. By focusing on secondhand harms, we are reminded of the costs that an out-of-control party subculture can have on the entire college community.

Q: You suggest administrators are complacent with the party culture and in some ways even benefit from it, but of course every major four-year residential university has some sort of anti-binge drinking education. Particularly with regard to taking advice from students, what are administrators not doing to address this problem that they should be, and why do you believe they haven't done so already?

A: I think that most schools try to educate students about the problems linked to alcohol and drugs, but the education is usually “white noise” that students readily dismiss. After all, they already know that partying comes at a cost. I argue in the book that most students who party recklessly willingly take these risks; many see occasional injuries or black outs as collateral damage or the price they must pay for the admission to the party. Therefore, the only program that would effectively keep students safer, and that students themselves support, is the implementation of medical amnesty programs, where students can be assured that if they call 911 to get help for themselves or friends in crisis, they will not face legal consequences for underage drinking or illicit drug use. Schools may be hesitant to implement these programs because they don’t want to appear to condone drinking and drug use. But if safety is a priority, these programs would be the most effective way to reduce potential tragedies related to partying.

Q: Many prevention experts believe community approaches to combating binge drinking -- for example, a college teaming up with local bars to end "ladies drink free" nights, while also stepping up police patrols in "hot spot" party areas -- are the best shot they have at reducing injury and crime. But you note that businesses and universities may be reluctant to take this approach. Is that a bad thing, and why?

A: While it is easy to see why bar and club owners are reluctant to eliminate drink specials or other promotions – after all, they make their profits from student drinking – it is more difficult to understand why university administrators, police and local town officials have not been more effective in reducing some of the problems caused by the party subculture. In the long run, it really boils down to a rather controversial reality: the party school is itself a business, and alcohol is part of the business model. Schools lure students to attend their schools with the promise of sports, other leisure activities and overall fun. Part of this fun, whether schools like it or not, is drinking. Thus, even as university officials want to keep students safe, they also need to keep their consumers happy. This means letting the alcohol industry do what it does best – sell liquor.

As for the police, they have a super tough job at these large residential schools. Young people in general are often mistrustful of the police, and this distrust is magnified at the party school where, dependent upon how much they party, students see the police as either ineffective in controlling their peers’ out-of-control behaviors, or as bullies who interfere with their “right to party.” In many ways, the police are damned if they do, damned if they don’t.

Q: You talk a lot about students' unwillingness to seek help from police when they suffer negative effects from alcohol – because they don't consider a problem a "real crime" or think they should deal with it themselves, they don't like cops, they believe police are ineffective, or they don't want to get in trouble. Are there any ways to improve officer-student relations on campus?

A: As I mentioned earlier, it makes very good sense to promote a medical amnesty policy that would encourage students to get help when it is needed. It is one of the few things that can be done to keep students safe. I also think that implementing community policing strategies could be helpful for demonstrating to students that the police are accessible, are sensitive to their needs, and are not the enemy. Even though getting students to trust the police is an uphill battle, it would certainly be a great start for reducing problems in neighborhoods by encouraging students to report crime and cooperate with police.

Q: Partying -- along with its negative effects -- is most extreme among fraternity and sorority members and athletes, you note several times. Does your book contain an indictment of Greek life and athletic culture in particular?

A: Actually, drinking and drug use is only slightly more extreme among these groups. Further, the harms that students experience while intoxicated are similarly distributed among Greek and non-Greek members, and athletes and non-athletes. But even though certain athletes, especially football and basketball players, can sometimes act out recklessly and with immunity, their celebrity can be useful for positive change. For instance, because athletes are highly respected among their peers at sports-oriented universities, they could successfully dissuade students from rioting after games, or behaving in disruptive manners during games. As it stands now, poor sportsmanship has become a symbol of school spirit or pride. I believe that athletes, and their coaches, can reverse this trend.

Q: You note that there is sometimes a contradiction between policy and practicality – for example, police only have the capacity to arrest the rowdiest of students on game days, even though many students violate the student code of conduct. How big of a problem is the fact that sometimes campus policies just aren't enforceable?

A: As a criminologist, I believe that lack of enforcement is a fundamental problem. Rules are useless unless they are enforced. Students, like all of us, weigh the risks of their behaviors against the rewards. If they assume their risks of getting into trouble to be low, they are more likely to act recklessly. On paper, most schools and communities advocate for zero tolerance. They have strict laws and codes of conduct with serious penalties for violations. Yet, reality is much more complicated. It just isn’t practical for police to arrest every student who misbehaves. And even if they did, it is doubtful that it would deter students from partying. For instance, where I work, the police spend a lot of their time writing citations for underage drinking and public intoxication. But it does not seem to deter students under 21 from drinking, or students of any age from partying recklessly.