You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

WASHINGTON – The U.S. Department of Education’s rulemaking session on “gainful employment” regulations ended Friday in a stalemate.

A panel of department-appointed negotiators was unable to reach consensus on the proposed standards for vocational programs at for-profit institutions and community colleges. Dissent came from representatives of both the for-profit and consumer-group camps.

The feds will now submit their own final draft of the regulations for a public comment period. They are not required to listen to suggestions negotiators floated during rulemaking meetings. But a department official said they would try to incorporate some of what they heard.

“The department is not bound by the proposed language that we worked on today,” said John Kolotos, a department official who served as the federal government’s lead representative during the process. He said participants’ views “will be carefully considered” as the department works on the draft regulations, which he said should be released early next year.

Friday’s meeting was the last of three sessions held here in recent months. The department revised drafts of the rules twice during the negotiations.

In November the department added a minimum loan repayment rate to the two other metrics, which would set minimum floors for a program’s cohort loan default rate and for the debt-to-income levels of graduates.

(Ben Miller, a senior policy analyst with the New America Foundation and former department official, wrote an account of the negotiations as well as an analysis of the latest draft proposal. Miller is supportive of the Obama administration's gainful employment push, but his write-ups provide a detailed description of the process.)

The inclusion of a loan repayment rate made the rules stiffer than both this year's first draft and the final language from the last battle of gainful employment, which resulted in regulations a federal judge threw out last year.

The for-profit sector complained about the new repayment metric. The department apparently listened, and dropped it for the third draft, which was publicly released less than 48 hours before the Friday meeting.

For-profit negotiators praised the department for softening the proposed standards.

“I was very concerned with where that second proposal was going,” said Brian Jones, Strayer University’s general counsel and a negotiator for the sessions. “I do appreciate the tone the department has set.”

However, for-profit representatives remained critical of the proposed rules, both over technical aspects of the metrics and the overall approach. Jones said the department made too many "unjustified" decisions in creating them.

Consumer advocates were harsh in their criticism of the department for dropping the repayment rate, pushing hard for it to be restored. They said the standards, as currently structured, would not go far enough in protecting students from predatory colleges.

Several times on Friday Barmak Nassirian, a negotiator, bemoaned the department’s “evisceration” of the proposal since the last meeting. Nassirian, director of federal relations for the American Association of State Colleges and Universities, called the draft rules a “regulatory shell” that will be “nothing but a placebo for the disease we’re trying to cure here.”

The philosophical divide over gainful employment has also been playing out on Capitol Hill.

A group of 30 Democratic members of Congress on Friday wrote to Arne Duncan to express concern over the process and what it could mean for President Obama's proposed ratings plan for colleges. They said the department should seek to avoid harming students with the regulations, particularly students from underserved populations.

Not to be outdone, 31 other Democrats also wrote to Duncan last week. They said the need for regulations that protect students is stronger than ever. One of the letter's authors, Rep. Elijah Cummings, a Democrat from Maryland, even briefly attended the negotiations on Friday.

"Too many have left these schools with nothing to show for their time and money other than insurmountable debt," Cummings said in a written statement. "If these institutions are truly committed to educating students from underserved communities, they need to be equally committed to demonstrating positive outcomes for those students."

Looming Legal Fight?

The for-profit sector’s trade group, the Association of Public Sector Colleges and Universities, filed the lawsuit to challenge the department’s last attempt to set gainful employment standards.

In his ruling, the federal judge said the department was within its rights to try to adopt rules to prevent federal financial aid from flowing to programs at underperforming colleges. But he said the feds had failed to adequately justify the setting of a minimum loan repayment rate.

The threat of another lawsuit was hinted at several times during the Friday session.

The for-profit association was fiercely critical of the process, releasing a statement claiming the department had acted arbitrarily and also failed to adequately evaluate the rules’ impact on students. They said the rules were bad public policy that could displace millions of students.

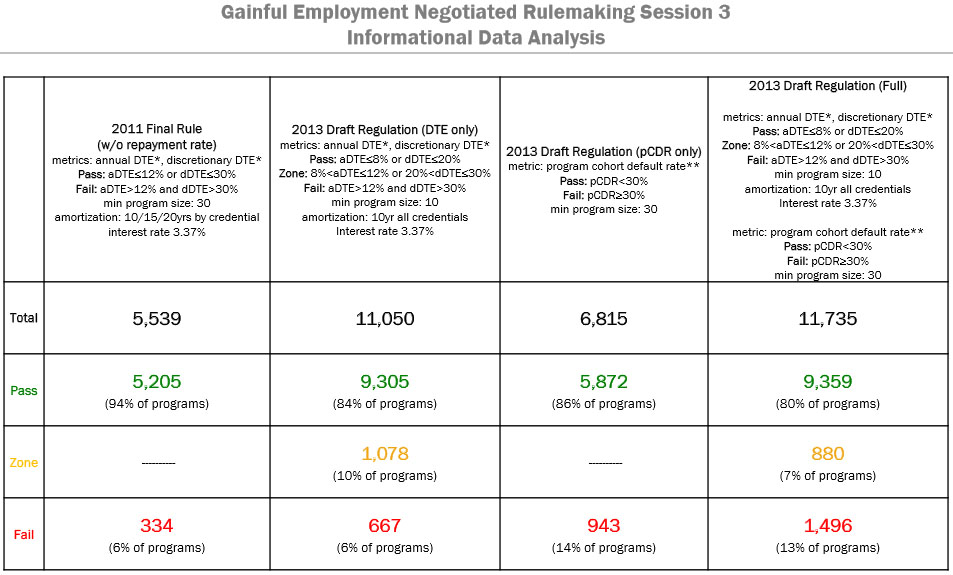

Negotiators for the for-profits said the department had not given participants enough time to review data on how programs would fare under the revised proposal. Those numbers, which were released late last Wednesday, showed that 13 percent of the 11,735 programs that fall under gainful employment would fail the standards and risk losing eligibility for student aid. Another 7 percent would land in a warning “zone.”

The vast majority of failing programs would be at for-profits. Only 53 community college programs would be among the 1,496 that would fail, according to an analysis conducted by the Association of Community College Trustees.

However, for-profit college officials said the two metrics don’t succeed in identifying “bad actor” colleges, because relatively few programs fail both.

Only 113 for-profit programs would fail the debt-to-earning metric and the cohort default rate, according to an analysis by the for-profit association.

“If these two metrics are intended to identify programs that leave students with ‘too much debt,’ they should be identifying many of the same programs,” a spokesman for the association said in an email. “This is clearly not the case.”

Negotiators for the for-profit industry suggested several tweaks to the standards. For example, Marc Jerome, executive vice president of Monroe College, proposed that colleges with failing programs be able to submit plans to the department for reducing the debt loads of students.

The department responded last week with its interpretation of that idea. Several consumer advocates criticized the concept, however. And it was unclear whether Jerome’s proposal will make it into the final draft.

For-profits scored a minor victory with a suggestion to drop student borrowing for expenses other than tuition and fees from the debt-to-income threshold. The department incorporated that suggestion in its most recent draft.

Nassirian and others pushed back, arguing that borrowing to pay for books and other academic-program related supplies are not voluntary expenses. The feds apparently agreed and Kolotos said Friday that books and supplies would be added to the metric.

Negotiators representing community colleges said they could support the draft regulations if they included a proposal submitted by Kevin Jensen, financial aid director at the College of Western Idaho. That plan, which participants spent a good chunk of time discussion Friday, would exempt “low-risk” programs at community colleges.

For nearly all low-cost community college programs, he said the “loan debt incurred by a typical student is zero." Those programs should be exempt, he argued.

The department can make gainful employment palatable to the two-year sector with some slight modifications, Sandra Kinney, a negotiator and vice president of institutional research and planning at the Louisiana Community and Technical College System.

“I think it’s as close as we’re going to get,” she said at the session's conclusion.

For-profits and consumer groups were both much less optimistic. Both sides of the divide said they would need substantial changes to back the rules. So it’s a safe bet that plenty of people will remain disappointed by whatever the feds release next year.