You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Community college students who transfer to for-profit institutions tend to earn less over the next decade than do their peers who transfer to public or private colleges.

Those are the findings from a study released Monday by the Center for Analysis of Postsecondary Education and Employment, a research center that was created with a federal grant and is housed at the Community College Research Center (CCRC) at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

In recent years several researchers have attempted to look at the relative labor market returns of attending for-profits, which is also a hot topic among policy makers.

There are many variables at play – such as the relatively low academic preparation of incoming for-profit students versus their peers at traditional colleges. And the results from those research efforts have ranged from largely unflattering to a mixed view of for-profits.

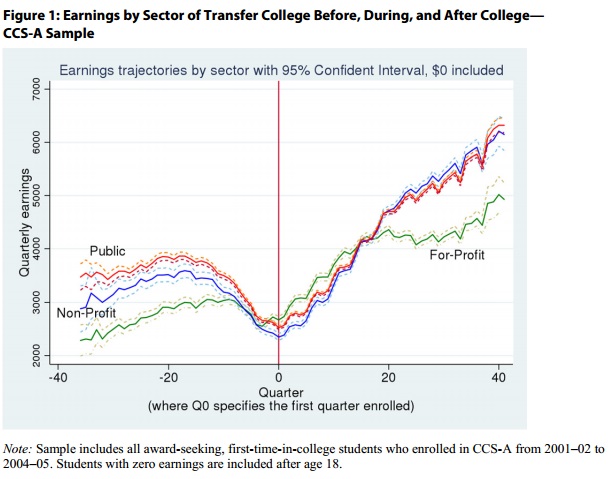

This new study, however, may be the first to analyze earnings gaps at various points before and after students attend college, as well as while they’re still enrolled.

It also controlled for the effects of student “swirl” in the complex higher education system by looking at transfer among a large sample of 80,000 full-time community college students who first enrolled in the early to mid-2000s.

Over all, the research found that students who transferred to for-profits earned roughly 7 percent less over the next decade than students who transferred to private or public nonprofit institutions, according to income data culled from unemployment insurance data dated from up to 2012.

“We identify a statistically significant wage penalty from enrolling in a for-profit institution,” wrote the study’s coauthors, Vivian Yuen Ting Liu, a senior research assistant at the CCRC, and Clive Belfield, an associate professor of economics at Queens College, which is part of the City University of New York System.

“This penalty appears consistent across subgroups of students, although it is greatest for for-profit students who did not complete an award,” they wrote. “For-profit students gain least over the longer term. Extended over a working life, the differences become much greater.”

Work and study

The research was based on cohorts of students who attended community colleges in two statewide systems.

Among students from the first group, which included data from a longer time range, there were stark differences in the earnings gains one decade after transfer. Students who attended for-profits had a net wage bump of $5,400 over that decade. But public college students saw a $12,300 gain and private college students earned $26,700 more (in 2010 dollars).

The results were more mixed for the second cohort of students, who attended community colleges in a different state.

In that group, students who transferred to a for-profit sometimes earned more than their peers who transferred to other institutions. For example, both men and women who transferred to for-profits earned an average of 18 percent more than students who transferred to public colleges.

One reason for the discrepancy was that the second group was tracked over a shorter period of time. Those students first enrolled in community college a few years earlier than the other, larger group, and therefore had less time in the labor market.

Additionally, students fared better while they were enrolled in for-profits, according to the study.

“The for-profit students can work more intensively while they are studying,” Belfield said. And the associated impact on earnings persists for up to five years.

But the smaller “opportunity costs” of attending a for-profit were erased over time. And the second group of transfer students likely had not yet had enough time in their jobs to see their earnings losses offset from enrolling in nonprofit colleges.

A spokesman for the Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities said the study exposes differences between the for-profit sector and nonprofit institutions.

“Our students are more likely to work during school and can have more difficulty in the classroom,” Noah Black said in a written statement. “But the path to success for these new traditional students is still through higher education, and our goal is to give them that opportunity they would not have otherwise."

Belfield said he hoped the findings would help students focus more on their long-term earnings.

“Most of these students are still pretty young,” he said, and should be asking, “What’s college going to do for my career?”

'Better than Nothing'?

The study sheds light on the characteristics of community college students who tend to transfer to for-profits. On average, this group fares worse academically before transferring.

“Students in the for-profit sector accumulated far fewer credits before they transferred, were more likely to transfer without an associate degree and had much lower GPAs at their college of first enrollment,” the study found.

In addition, black and Hispanic students in the larger cohort were more likely to transfer to a for-profit -- by a substantial margin.

That difference between students who transferred to for-profits or nonprofits offers a caveat to the research, Belfield said, because they suggest that there may be various reasons why many of the for-profit students did not thrive at public, two-year colleges.

Belfield also cautioned against judging all for-profits alike. The industry is large and “pretty heterogeneous,” he said. And the study did not break out its findings along institutional lines.

However, while the research found that all students earned more if they continued their studies after community college, transferring to a for-profit appears to not pay off as well, at least on average.

“Something is better than nothing,” Belfield said, but “you’re taking a bigger risk if you go into the for-profit system.”