You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Colby College

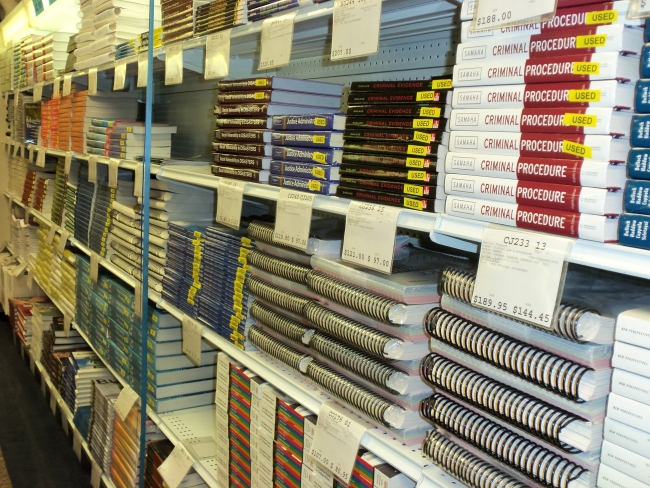

Despite some recent improvement in textbook market options and transparency, rising prices continue to hinder students who, in the worst scenarios, are turning down classes because the materials are too expensive.

“The problem is as dire as ever,” Ethan Senack, a higher education associate at the United States Public Interest Research Group, said in a conference call announcing the findings of the Student PIRGs’ latest report on textbook costs and how students are responding. “The federal government, states and most important, individual campuses, need to support and invest in alternatives outside of the traditional textbook market.”

The survey, which includes about 2,000 students from 150 campuses, indicates that while cheaper alternatives such as rental programs and open-source textbooks have gained traction in recent years, 65 percent of students had still opted against buying a book because it was too costly – and 94 percent of them were concerned that their grade would suffer because of it.

Another 48 percent of students said the cost of textbooks affected how many and which classes they took each semester. At the same time, 82 percent of students said free online access to a textbook (with the option of buying a hard copy) would help them do “significantly better” in a course. The paper therefore argues for widespread use of open textbooks, which are designed in this way and which PIRG estimates save students an average of $100 per course.

“Students should be focused on taking the classes they need, not kept out because they feel they have to choose between their textbooks and rent,” said Senack, the report’s author. “We know that if more campuses and if more states made the commitment ... we would be able to save students millions in dollars per year.”

PIRG, whose previous reports have been disputed by textbook publishers, notes that a single textbook can cost more than $200, and that the College Board estimates that students will spend on average $1,200 on textbooks and other course supplies this year.

Students head to campus already expecting to pay thousands in tuition and fees, Samantha Zwerling, student body president at the University of Maryland at College Park, said on the call. “A thousand dollars a semester for textbooks is the real kicker.”

But David Anderson, executive director of higher education at the Association of American Publishers, called the report “transparently biased and distorted.” For example, he said, how many of the 65 percent of students who didn’t buy a required textbook opted for a rental instead – and who’s to say they suffered academically because of it? (According to the research firm Student Monitor, close to 10 percent of students now rent textbooks, while half as many use ebooks.)

“I think it’s hard for the authors of this report on the one hand to laud the increased use of rentals and the increased availability of open source, and then not give you a breakdown of how they’re being used,” Anderson said.

He also noted that the inflation rate cited in the report reflects just the rising cost of traditional hardbound textbooks, when students have a variety of options including three-ring binder, digital and by-chapter editions. “It’s very misleading to rely solely on those numbers.”

The U.S. and state PIRG groups have been instrumental in getting legislation on the books that makes textbook pricing and edition-change information more accessible to faculty members, who they say have historically had trouble figuring out how much textbooks will really end up costing their students.

For open-source ideas, faculty, administrators and state legislators should look to the University of Minnesota Open Textbook Library, the University System of Maryland’s Open Source Textbooks initiative, and the state of Washington’s Open Course Libraries, the report says. In addition, students should advocate directly for open textbook use, and publishers should “develop new models that can produce high quality books without imposing excessive prices on students.”

Open textbooks are similar to e-textbooks in that they can be read electronically, but the latter expire after 180 days and still cost up to half the print retail price. E-textbooks are “just a continuation” of publishing companies’ control over the market, the report says.

PIRG argues that consumers are helpless at the will of the publishing companies, who control prices by releasing new editions every few years and mark up costs an average 12 percent each time, while clearing the shelves of any old editions. Additional “bundles” – packaging books with online materials or CDs – can drive up prices by as much as 50 percent.

According to a June 2013 Government Accountability Office report, textbook prices rose 82 percent between 2002 and 2012, at three times the rate of inflation.

Irene Duranczyk, an associate professor of postsecondary teaching and learning at the University of Minnesota who uses open textbooks, said she has also seen students priced out of classes due to textbook costs. In fall 2012, Duranczyk began substituting a free open textbook that had an optional $32 print version for her regular $180 book.

"I believe that high-quality course materials are essential, and I want to be sure that all my students have access to those materials,” she said. “On the whole, students were very, very appreciative for being assigned a textbook that didn’t break the bank.”

While use of open-source textbooks is still fairly uncommon, more than 2,500 professors have signed PIRG’s Faculty Statement on Open Textbooks professing their support for the innovation, the report says.