You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A new survey of 30,000 college graduates gives higher education leaders a chance to make their case that college isn’t all about jobs and income.

The evidence from the largest survey of its kind is, however, mixed about whether colleges are doing enough to help students’ well-being in life, according a new measurement designed by Gallup and Purdue University.

Researchers found that certain sorts of formative experiences in college help prepare graduates for not only "great jobs" but "great lives," but that too few graduates recall having had those experiences.

The survey comes as Gallup, which has long studied “well-being,” is looking to help individual colleges examine the devotion and success of their alumni.

A major finding suggests that the type of institution students attend does not matter – little more, if any, additional well-being can be found among graduates of Ivy League colleges than alumni of other types of colleges, according to the results.

The firm found liberal arts majors were slightly more satisfied with their jobs than were business and science majors, though the latter were more likely to be employed full-time. The survey’s results also suggest student loan debt can make graduates risk-averse.

The national study, which Gallup expects to repeat each year, found that if working graduates remember having had a professor who cared about them, made them excited to learn and encouraged them to follow their dreams -- which Gallup called being "emotionally supported" while in college -- the graduates’ odds of being engaged at work more than doubled. But only 14 percent of graduates recalled having a professor who did all of those things.

Graduates whose college experiences included forms of "experiential and deep learning" -- working on a long-term project, having an internship with applied learning, and being extremely involved in extracurricular activities --were also twice as likely to be engaged in their work. But only 3 percent of graduates said they had all six of the formative college experiences that meant they had both emotional support and deep learning.

“If these magical but relatively simple elements happen to you, it’s a profound game-changer for your life and career,” said Brandon Busteed, who leads Gallup's education work. But, he said, not enough students have such experiences.

Peter McPherson, president of the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities, said the low number of students with memorable mentors, projects and activities isn't what he'd like to hear -- but the information is good to know.

"I think that the only thing worse than having troubling data is not having data at all," McPherson said.

The Context, Federal and Otherwise

To do the survey from early February to early March, Gallup recruited college graduates of all ages by randomly dialing telephone numbers and then asking willing participants to fill out an online survey after the call. About 29,560 people with a bachelor’s degree or higher responded, as did 1,557 with an associate degree.

The survey is the first of what Gallup plans to make an annual affair. The firm, which carefully rolled out its findings, is also hoping to drum up business for the survey as college officials seek to study alumni satisfaction – provoked perhaps by the idea that salaries right after college are not a good measure of college’s worth. Those sorts of measurements contrast with some of those being explored by the federal government, which would measure completion, salaries after graduation, recruitment of low-income students and more.

“If we focus on how much money people make, we can really run people afoul,” Busteed said.

Molly Corbett Broad, president of the American Council on Education, said Gallup’s work bolsters prior studies and produced some novel findings that may pique college officials' interest. But she said it wasn't clear whether the polling firm’s history of work on overall well-being can be applied to the college experience to find differences among institutions.

“I think we don’t know enough from what we’ve seen so far to give us great insights about different colleges,” she said.

Gallup is planning to do more to break down its findings in coming months. In recent days it made available a summary report and a slideshow of its top-level findings.

Among those findings:

- Graduates who reported higher loan debt were less likely to start their own business. “No surprise that if you hold more student loan debt, then you’re likely to be risk-averse, and that I think is not a trivial revelation,” Broad said. “But again you don’t know what else may be going on in their lives.”

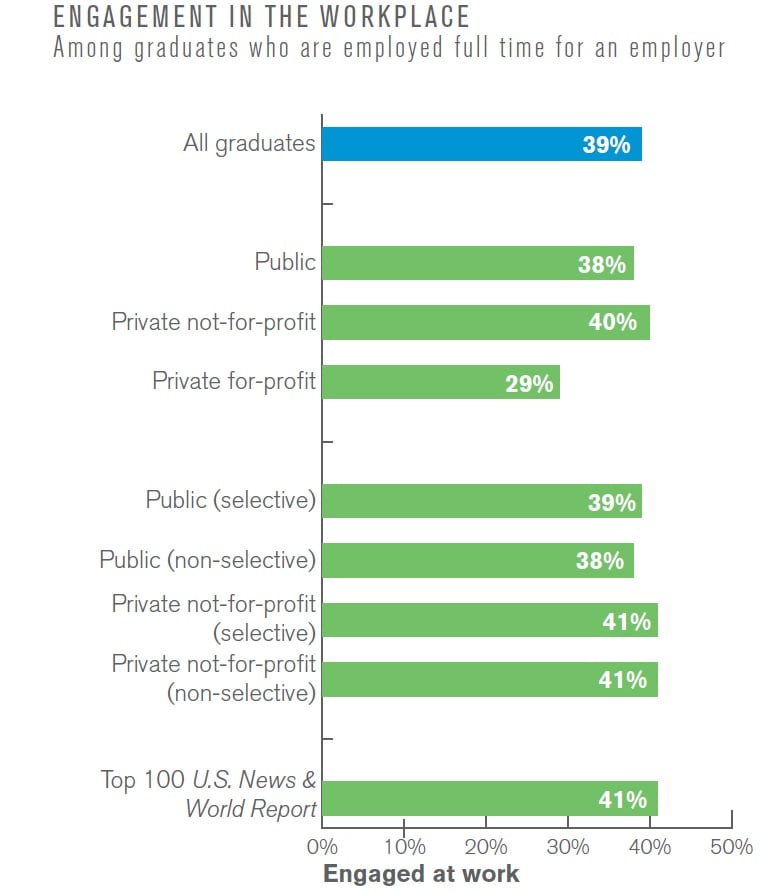

- There’s little to no difference in well-being among graduates of Ivy League colleges, universities with different Carnegie classifications or among the “Top 100” colleges as labeled by U.S. News & World Report.

There are two exceptions to that finding.

Graduates of for-profit colleges were less likely to be engaged at work.

There is also a small but noticeable difference between students who attended colleges with enrollments above or below 10,000: graduates of the smaller colleges were less likely to be engaged at work. “That’s a stumper,” Busteed said.

Broad said the findings are counterintuitive given the importance of close attention from professors. She said that finding will need to be given careful review.

While science and business majors were more likely to be employed, social science and arts and humanities majors were more likely to be engaged at work.

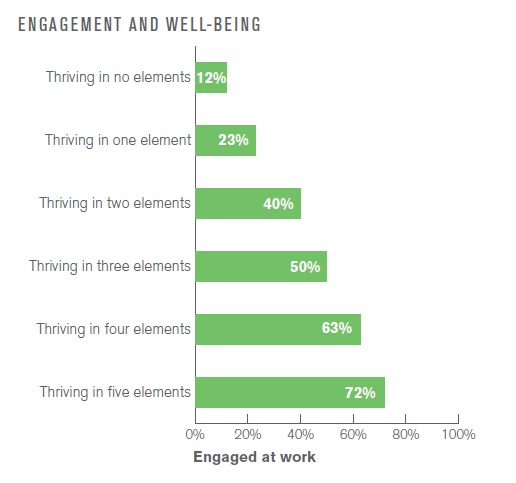

Gallup believes five areas make up well-being: social, financial, purpose, community and physical. It found, rather alarmingly, that one in six Americans do not believe they are thriving in any of those areas and only 11 percent report they are thriving in all five elements.

Female graduates were less likely to have full-time jobs but more likely to be engaged in their work than were men.

Gallup’s survey will start a conversation that a smaller study in an academic journal couldn’t, said Mark Schneider, a vice president at the social science research and evaluation group, the American Institutes for Research.

But he said that the findings – and the publicity push that accompanied their release – is meant to “drive business to their campus-based assessments” and that the findings, while a large survey, establish correlation but not causation.

“The 30,000 students in their survey are not going to be enough to do institutional-level analysis, so it will be just at a very high level,” Schneider said. “But that’s the advertising campaign to get schools to buy their institutional product.” (Schneider and AIR themselves have developed their own system for measuring college outcomes, based heavily on graduates' financial outcomes.)

Gallup, which has long studied “well-being,” has found in other surveys with different methodologies that about 30 percent of those in the American work force – a sample that includes college graduates – are engaged in their work.

By comparison, the Gallup-Purdue Index survey of college graduates found that about 39 percent of them were engaged -- though the researchers caution that the differing methodologies make the figures not directly comparable.

McPherson said he expected healthy debate about the Gallup-Purdue Index's findings.

"We've long struggled, and I know we're not through with finding a way to measure some of the less easily quantified outcomes of a college degree, and I've thought for a long time we've needed that," he said. "It's not going to have the precision you'd like to have perhaps, but I think it's an important component of looking at the outcome of a college degree."