You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

WASHINGTON – The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision last year to require a higher level of scrutiny for race-based affirmative action was a step toward destabilizing race-conscious admission plans, and universities must find new ways – for now additional ones, but eventually substitute ones – to ensure diversity.

That is one theme of a new book, The Future of Affirmative Action: New Paths to Higher Education Diversity After Fisher v. University of Texas, and it was a subtle but persistent subtext of a half-day discussion of the book here Tuesday. The authors, who participated in the event, spoke with varying degrees of directness about the threat posed to traditional race-conscious affirmative action.

While many of the participants stopped short of deeming traditional affirmative action a lost cause, all agreed that it’s time for institutions to put greater emphasis on other ways of promoting diversity.

“Take the opportunity of the Fisher decision, and other predictions some have made that the end may be near, to look at other paths,” John Brittain, a law professor at the University of the District of Columbia, said.

These other paths include considerations like income, family wealth, and even – as Georgetown University law professor Sheryll Cashin argues in her new book – place.

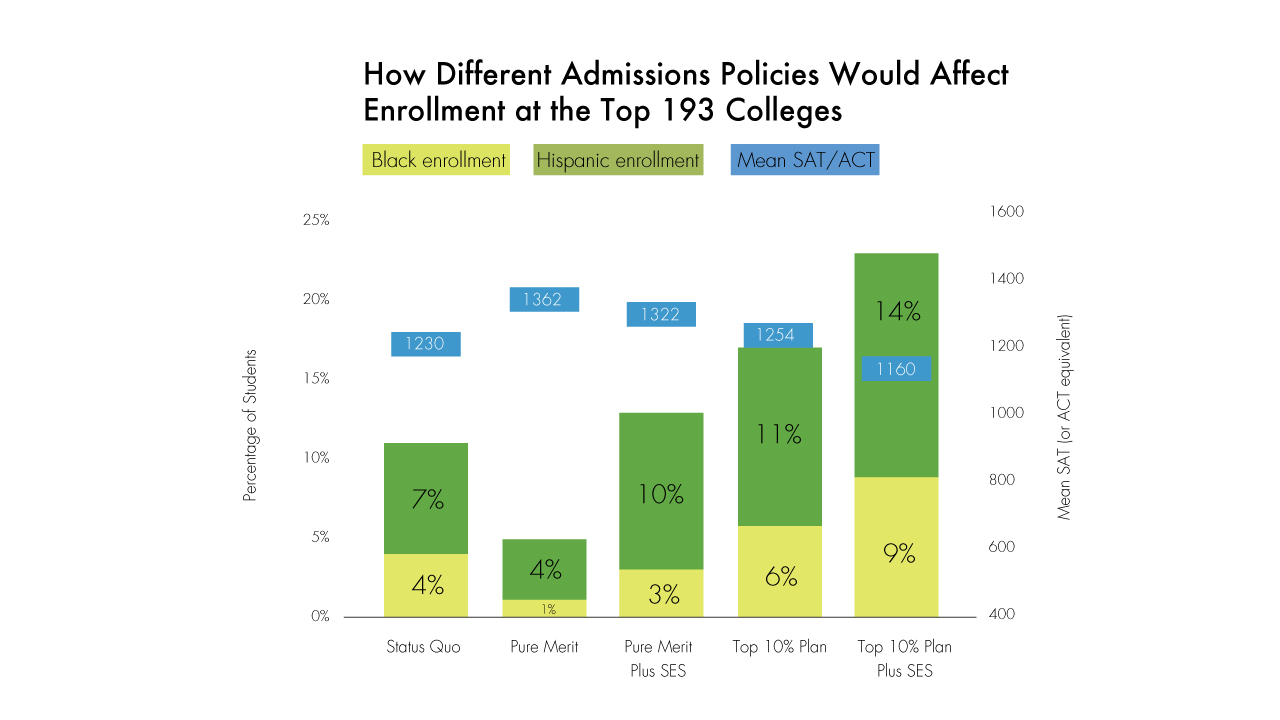

A combination of some race-blind approaches could actually be more effective at increasing the percentage of African-American and Hispanic students than the consideration of race alone, according to the projections of three researchers – including Anthony Carnevale of Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce – included in the book. Class-based criteria are especially effective at improving access for Hispanics, they said.

The current percentage of students at 193 selective colleges they identified who are African American is just 4 percent. For Hispanics, that number is 7 percent. One approach, which combines guaranteed admission for the top 10 percent of a high school class with a boost for socioeconomic factors, would double African-American enrollments and nearly triple Hispanic enrollments, the authors argue.

Percent plans like the one adopted by Texas, which provides automatic admission to the University of Texas to students who rank in the top 8 percent of their class, are an example of place- and socioeconomic- based admissions. UT-Austin saw its percentage of low-income students increase by 15 percentage points under the plan, according to the Lumina and Century Foundations, which co-published the book and co-sponsored Tuesday’s event.

At the University of California at Los Angeles’s law school, new class-based affirmative action policies there led to a much higher rate of black and Latino admissions in 2011.

Both institutions adopted the new admission policies after affirmative action was banned in Texas and California. Eight states so far, accounting for more than a quarter of the country’s population, have banned affirmative action. Their right to do so was upheld by the Supreme Court in April.

Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation and an advocate for class-based affirmative action for close to 15 years, said that the public doesn’t want to “re-segregate” institutions by barring affirmative action, and that many universities use the opportunity to find other ways of increasing diversity.

“You can’t just be against affirmative action,” Kahlenberg, who edited the new book, said. “You have to be for something else.”

Voter initiatives can pose a more immediate threat to race-based admissions than do lawsuits and Supreme Court decisions. While Catherine Lhamon, the assistant secretary of education for civil rights at the U.S. Department of Education, said “we’re some years off” from another case like Fisher reaching the Supreme Court, state-level bans happen with some frequency. Six of the eight states that have banned affirmative action did so in the last eight years.

Constitutional affirmative action bans can create a chilling effect on neighboring states, said Matthew Gaertner, a senior research scientist at Pearson.

“The thing about these voter referendums when they pass is that you don’t get a phase-in period,” Gaertner said. “You have to go immediately to race-neutral or race-blind admissions, so it’s really helpful if you have thought through and even experimented on some promising race-neutral alternatives.”

Georgetown’s Carnevale said the most effective way of addressing diversity in higher education is through a combination of socioeconomic and racial considerations.

That can be difficult when universities are told to separate the two, as they were with the Fisher decision, which charges universities with demonstrating that other diversity initiatives are insufficient before considering race as part of the admissions process.

“I can’t escape the feeling that what we’re trying to do and what the court is asking us to do is to talk about a thing without naming it, to find a solution to a problem without dealing with the problem directly,” Carnevale said. “That is, how do we address diversity without using race? How do we use proxies for the same purpose?”

In her dissenting opinion to the Fisher decision last year, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg made similar remarks, saying that “only an ostrich could regard the supposedly race neutral alternatives as race unconscious.” Kahlenberg said that whether they are viewed as true alternatives or merely as proxies, the goal is to make sure new pathways to diversity are “untouchable” by the Supreme Court and voter initiatives.

“It’s time for universities to do more contingency planning,” said Kahlenberg. “Lots of people in this room are still fighting for the ability to use race, but even among them there’s recognition that it’s time to get more creative.”