You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A growing number of states are using lottery money for college scholarships. But the politically popular lottery funds often fail to live up to their expectations, according to a new report from the American Association of State Colleges and Universities.

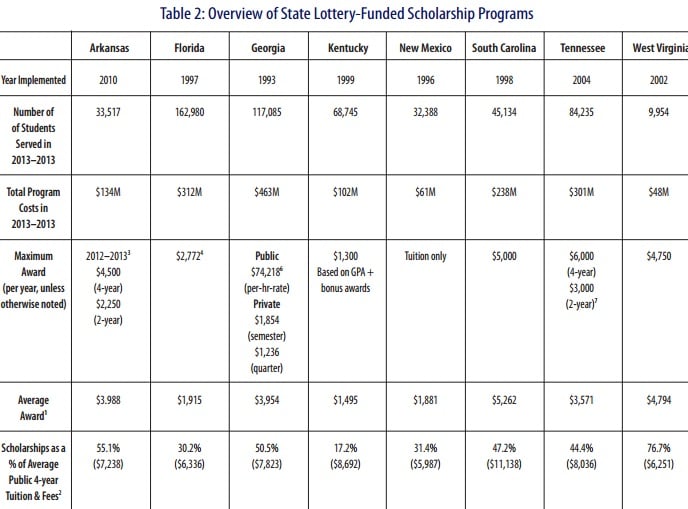

The report breaks down how 11 states have earmarked lottery revenue for higher education. Eight states, mostly in the South, use the money for merit-based scholarships (see graphic).

Lawmakers from both parties are drawn to the alternative funding streams, which are easier to tap for education than raising taxes. And trying to keep college affordable is a noble goal, according to the association.

However, the report describes possible unintended consequences from lottery-funded scholarships. They tend to supplant rather supplement general state support for higher education. And the money regularly does not help the neediest students as much as it does others.

Politicians can fix some of the problems with these programs, said Daniel Hurley, the association’s director of state relations and policy analysis.

“It’s about refining them,” he said, such as by shifting the focus to need-based rather than merit-based aid, which tends to disproportionately benefit wealthier students.

Kati Lebioda, a contributing policy analyst for the association, is the report’s author. A graduate student at George Washington University, Lebioda wrote a first draft of the white paper for a class in higher education finance that Hurley taught this spring.

One key problem she described is that lottery revenue is unpredictable. Initial gains tend to drop off after five years, due in part to interstate competition and the funds’ inherent inefficiencies -- overhead sucks up 66 cents of every lottery dollar on average.

As a result, lottery-funded scholarship programs struggle to keep up with student demand. States then are forced to tighten eligibility requirements. As with merit-based aid, that helps wealthier students, who tend to be better-prepared academically. So poor people, who are more likely to play the lottery, end up subsidizing students from middle- and upper-income families.

The scholarships also are typically “last-dollar” programs, meaning they cover tuition and fees only after existing state and federal aid sources have been tapped. That can be a problem for needier students, who struggle to pay for expenses beyond tuition, such as books, transportation, housing and childcare.

“Last-dollar tuition scholarships do not correct inequity in college access and affordability across socioeconomic brackets,” the report said. “In fact, when the scholarships are merit-based instead of need-based, these programs tend to increase inequity.”

Potential Fixes

Lottery-funded scholarships may bring in new money, but they often accompany state budget cuts.

The programs can lead to a “false sense of investment,” Hurley said.

The report cites recent research that found that after an initial bump, overall education spending decreases over time in states that earmark lottery funds for education. In contrast, states without lotteries spend about 10 percent more of their budgets on education.

Georgia’s lottery-based scholarship program was the trend-starter. Created in 1993, the Helping Outstanding Pupils Educationally (HOPE) scholarship initially covered the full tuition at in-state public institutions or provided a set amount for private colleges in the state. Georgia students with a minimum high school grade-point average of at least 3.0 are eligible.

The HOPE scholarships kept more Georgia students in the state and also increased the academic competitiveness of incoming students at the state’s public universities. The program spawned imitators, particularly in other Southern states.

Florida awarded lottery-based scholarships to the most students last year, according to the report, with 162,980 recipients. Georgia was second with 117,085 recipients. The two states also funneled the most lottery money to their programs -- $463 million for Georgia and $312 million for Florida. Tennessee’s scholarship, also dubbed HOPE, was third, with 84,235 recipients and $301 million in program costs.

Several of the 11 states with lottery-based programs, however, have experienced stagnating lottery revenues in recent years. To cope, some have capped scholarship award amounts or changed eligibility requirements. And, as the report notes, even Georgia in 2011 made tweaks that resulted in a 24-percent decrease in the number of students who qualified for the scholarships.

One possible solution would be for states to link their scholarships to institutional tuition policies. The programs would be more sustainable, the report argues, if the money could only be used at colleges that hold the line on tuition increases. (Legislatures could also do a better job of funding their public colleges.)

The report also uses a brief case study of a new lottery-funded scholarship program in Tennessee as an example of how states could make lottery revenue be more predictable.

The Tennessee Promise, which the state created this year, offers all the state’s high school graduates two years tuition-free at Tennessee community and technical colleges. Students must enroll full-time, earn a GPA of 2.0 and participate in eight hours of community service per semester to remain eligible for the scholarship.

Hurley called the Tennessee Promise the “biggest higher education policy proposal of the year.”

The state used $300 million in lottery reserves to pay for the program, as well as other funds. It put the money into an endowment, and will rely on interest and drawdowns from the endowment to cover the initial $34 million annual cost.

This is a more stable approach than annual budgeting from lottery revenue, the report said. It “cushions program funds from short-term uncertainties, like a year of low lottery sales.”

The report also praises the Tennessee Promise for lacking a merit component and being applicable to all graduating seniors. As a result it targets many students who otherwise would not have considered attending college.

However, there are several concerns with the program, according to the report. The scholarship faces some of the same last-dollar problems, such as the unequal burden for needier students to cover non-tuition expenses. And it may drive students to community colleges who could have succeeded at four-year institutions.

“The long-term implications of the Tennessee Promise scholarship will continue to be the subject of much scrutiny and analysis in the years, to come,” the report said.