You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

It’s hard to raise much excitement over a chart, but a recent one that breaks down how colleges can reduce the number of sections they teach and reduce faculty time while educating the same number of students might be getting there. But not all the excitement is positive.

The chart is part of a summary of Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation-funded studies by the Education Advisory Board, a business that produces research for colleges. The board looked at seven colleges, mostly regional public universities whose names have not been revealed, and tried to figure out what it costs to teach students. Analysts combed through 250 million rows of data to draw up reports that spelled out the costs of each student credit hour in each section in each department of each college.

It’s something some college administrators might have said a few years ago that they could not do in a logical way, and that faculty may be initially loath to see. But that work was finished in about eight months, and people who worked on it say faculty should pay attention because it could be beneficial.

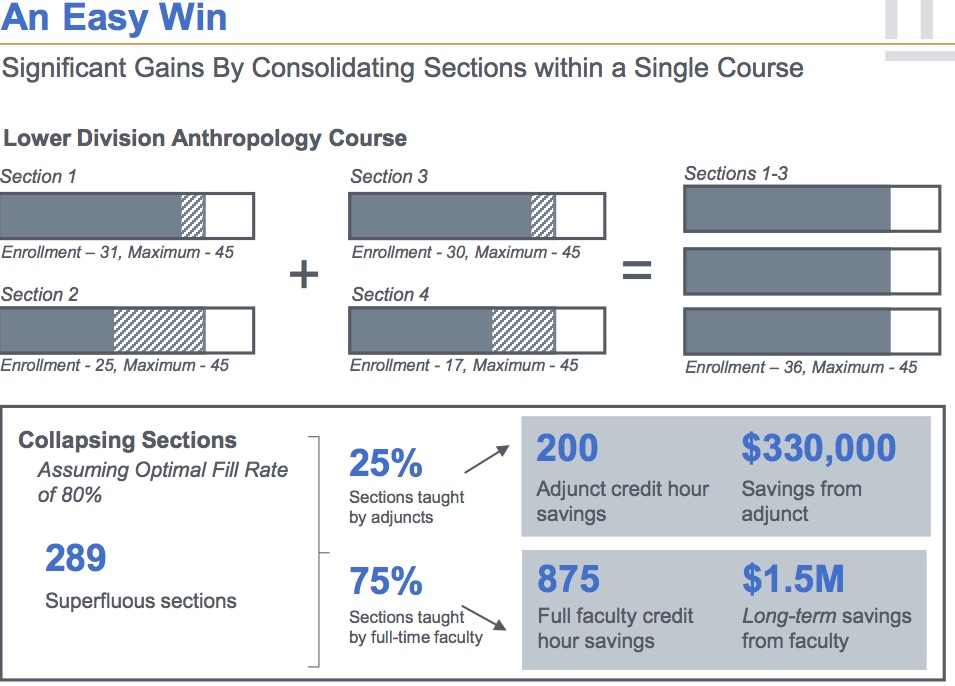

On a simple chart, the results are stunning: here’s how many classes are empty compared to the current maximum class size -- so, if you combined enough relatively empty classes, you could teach the same number of students without increasing caps on class size. The data also allow administrators to easily see how much it costs to teach the average credit hour in each department, a comparison that has been done elsewhere but that faculty say can be dangerous.

The goal of the studies was to control costs per student credit hour, find a way to collapse “superfluous sections” and prioritize investments in small courses.

“These numbers can be used to ask questions and important questions: Are we achieving what goals we ourselves in the academy have set?” said Chetan Rao, a practice manager at the board who worked on the report.

If a class can have 25 students in it, why should it only have 15?

Other colleges may have undertaken similar work on their own, but the new Gates-funded work may represent a shift because the Education Advisory Board is working up ways to reduce the time it takes to do the analyses and because it may provide a path to saving money for colleges without necessarily reducing the variety of courses offered.

Richard Staisloff, the founder of rpkGROUP, a consulting firm that advises colleges, advised the Gates Foundation on the project.

Staisloff said the advantage of the approach that the Advisory Board took is that it improves efficiency without necessarily reducing options.

For instance, the study used existing data on a course’s maximum capacity. But then it finds, in one example, that about 40 percent of sections are less than 70 percent filled to that level.

That solution isn’t necessarily to cut courses, but to collapse sections if many sections of the same courses are not filled up. One institution it studies could collapse 289 sections so that all of them were 80 percent filled and save $300,000 in adjunct teaching costs and $1.5 million in full-time faculty labor. Of course, some colleges could use the savings to help pay for small classes in areas where there are not sections to consolidate, or to add benefits for adjuncts or any number of things of which professors would approve. But of late, the skepticism about such studies has been that so many colleges have seemed anxious to have lists of courses or programs with relatively small enrollments and then eliminated them.

The Advisory Board’s work has not, at least as of a few weeks ago, been presented to faculty at the seven universities where it helped conduct detailed studies of what is essentially faculty productivity. It’s not clear when that will happen or in what form, or how the faculty at these unnamed institutions will react.

The University of New Mexico undertook its own separate study that looked at many of the same things.

Kevin Stevenson, the university’s director of strategic projects, said New Mexico identified 500 courses out of 10,000 sections where the number of empty seats was greater than the average class size. So, instead of offering four math classes with a faculty-determined maximum class size of 25 that only had 15 students, maybe it would make more sense for the university to offer just three sections.

Clearly, he said, some underfilled sections may be that way for a reason. Some class times may be more convenient for students, for instance.

Stevenson said the university is not going to tell faculty what sizes to make their classes. He said administrators trying to dictate the curriculum to faculty is a “recipe for disaster.”

But, he said, “If the appropriate size of the class is 26, then yes, I’d like you to have 26 students in the class, instead of 15.”

Besides collapsing sections, New Mexico can also use the data to try to recruit students for classes that have room left in them. Stevenson said the university is trying to beef up its strategy around transfer students by working with community colleges.

Some faculty may well be dubious.

“My view on all of this is that it is an exercise not worth undertaking,” said Howard Bunsis, a professor of accounting at Eastern Michigan University who is often critical of college administrators’ approach to budgeting.

He said the numbers would be used to not hire full-time faculty, hire more part-time faculty and increase class sizes.

In an email, Bunsis called the work a way to go about “gutting the heart of our universities.”

At the University of New Mexico, faculty reaction was “mixed.” Stevenson said the goal was to make the university a more effective public flagship research university, not do anything that would undermine that.

“It’s not saying, 'Education, I want you to be as good as business,' ” he said. “It’s saying to both education and business, 'I want you to be better tomorrow than you are today.' ”

Staisloff said the work represents new faith in the idea that existing higher ed institutions can change themselves. That means a shift away from the idea that existing institutions are not going to change on their own and that new business models — and whole new educational entities, like startup online colleges — needed to be created in order to save costs and expand access.

“While that’s important, I think people are coming back to the idea that traditional forms of higher ed are going to be able to adopt new models and new ways of thinking because that’s where most of the students are,” he said.