You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Women who rise to the position of chief security information officer are already a rare sight in higher education, but over the next decade and a half, they may become an endangered species.

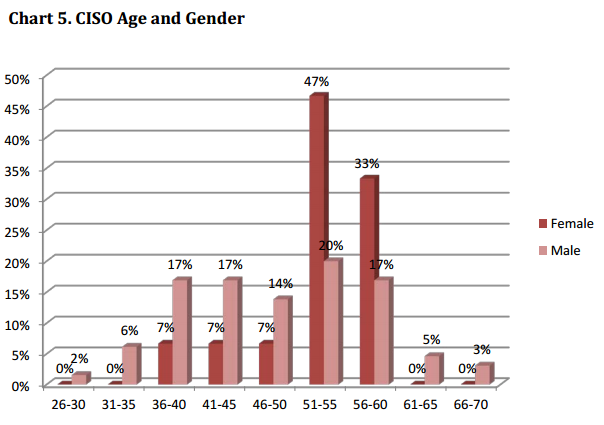

The 2014 Higher Education Chief Information Security Officer Study, released this week, contains grim news about the future of university IT offices, where men already far outnumber women. Four in every five CISOs who are women are 51 years or older, and two in five plan to retire within the next 10 years.

“In the younger age brackets, women were represented in single digits,” Wayne A. Brown, founder of the Center for Higher Education Chief Information Officer Studies, or CHECS, writes in the report. “Their anticipated retirement combined with the differences in age for the men and women CISOs strongly suggest that the percentage of female CISOs will further decline in the future if the present circumstances remain unchanged.”

Men, in comparison, are more evenly distributed between the ages of 36 and 60, suggesting their numbers will remain steady over the next several years.

CHECS has surveyed chief information officers since 2009 and found similar results, but 2014 marks the first year the nonprofit has conducted a separate survey of CISOs. Of the 254 invited to take the survey, 80 responded. (The survey retails for $35. CHECS provided access to the survey for free.)

The gender disparity among CISOs is slightly more pronounced than among chief information officers. Nineteen percent of CISOs are women -- compared to 22 percent of CIOs -- and the number has ticked down from 21 percent in 2009.

CISOs are less diverse generally. Only 5 percent of the survey respondents identified as non-white.

Tammy L. Clark, chief information security officer at the University of Tampa, said the numbers are disappointing, but not surprising.

“CISO is not an entry-level job by any means,” Clark, who is also a member of Educause’s Higher Education Information Security Council, said. “The women who are CISOs now, they really are at the midpoint or later in their careers, because most of us obviously started in IT and segued into information security. That’s what I did.”

Clark also said she expects the numbers will improve, but that it will take time for college departments to figure out how to attract and retain women who want to study science, technology, engineering and math -- and then even more time to sell them on a career in information security.

“In some cases, I don’t think they find it sexy and exciting,” Clark said. “There are lots of career paths in information security now. It’s not a one-trick pony.”

While the numbers from the survey may suggest otherwise, Clark said she feels the field is more welcoming to women than ever before. When Clark in 2000 was appointed CISO of Georgia State University, “there were almost no women,” she said. “At the time, women were not really accepted in the field, and I experienced a lot of opposition from male counterparts.”

Other CISOs disagreed with Clark's optimistic outlook. Arlene S. Yetnikoff, director of information security at DePaul University, said the gender ratios seen in information security programs today are “extraordinarily poor.”

“Ten years ago, anecdotally, it seemed better than what I see today,” Yetnikoff said.

Yetnikoff also pointed to the female CISOs recognized for their work in the field. This year, two women -- Yetnikoff included -- were named finalists for the 2014 Chicago Area CISO of the Year Award.

In the report, Brown suggests the path most people take to the CISO position may explain why women are underrepresented. That path often winds its way through IT networking, a field with more men than women. And since the CISO position, like the CIO position, is a relatively new one on college campuses, many of those who have been appointed have decades of experience working in IT offices that were once more male-dominated than they are today.

In fact, 63 percent of the surveyed CISOs previously held positions in IT departments at colleges and universities, and beyond higher education, 88 percent of the CISOs came from IT departments in general. More than half of the CISOs worked for their universities in a different role prior to holding the position.

Recognizing the importance of IT security to fend off malicious attacks, some institutions have their CISOs report directly to the president. That includes Tampa, where the two officers work together. Clark said she much prefers that configuration. “In two years, I’ve accomplished what it took me 12 years to do at my last university,” she said.

In most cases, however, CISOs still report to the university CIO -- 79 percent of respondents picked that option, compared to 4 percent who report to the president. Ideally, though, 26 percent of respondents said they would rather report to the president, and 33 percent to the CIO.

Some institutions have answered that organizational question by having one person perform both roles, but the survey results show the positions aren’t interchangeable. Unlike CIOs, who value technology skills, CISOs are more likely to value soft skills, including communication skills, leadership and relationship-building.

“I feel like this is opening up a lot of dialogue with CIOs and CISOs,” Clark said.