You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

College athletes are graduating at record rates, the National Collegiate Athletic Association announced Tuesday.

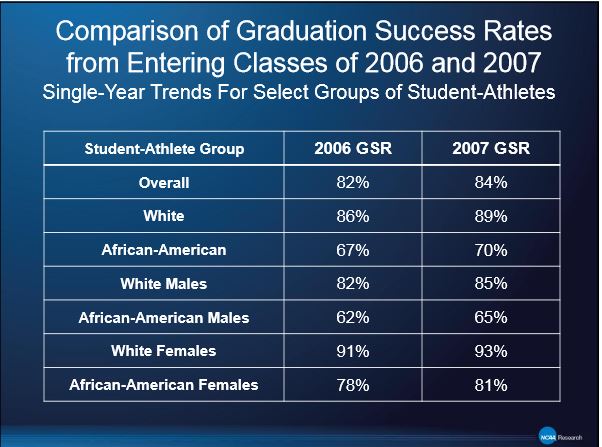

Eighty-four percent of Division I athletes who entered college in 2007 graduated within six years, according to the NCAA’s most recent Graduation Success Rate data, an increase of two percentage points from last year. Football players in the Football Bowl Subdivision -- the NCAA's highest competitive level -- graduated at a 75 percent rate, a 4 percentage point increase and an all-time high for the FBS.

Black football players within the FBS also graduated at record rates this year at 68 percent. The overall rate for black athletes, which has typically lagged behind that of white athletes, was 70 percent, a 3 percentage point increase from last year. Women continue to outpace their male counterparts, with white female athletes graduating at a rate of 93 percent and black female athletes graduating at a rate of 81 percent. The rates for white and black male athletes were 85 and 65 percent, respectively.

The NCAA credits the higher rates to ongoing academic reforms, including creating long-term Academic Performance Program penalties.

Across the board -- and as usual -- the Graduation Success Rate for colleges was higher than the federal graduation rate. The GSR counts athletes who transfer into a program and earn degrees as graduates, while the six-year federal rate does not. The GSR also excludes athletes who leave in good academic standing and transfer to another school, therefore not counting them as non-graduates. The federal rate this year was 66 percent, which fell short of the GSR’s 84 percent but is still the highest federal graduation rate ever recorded for college athletes.

Similar discrepancies can be found at many individual NCAA institutions, though for some programs that difference is more of a chasm.

The GSR and the federal rate for Iowa State University’s men’s basketball team, for example, tell very different stories. The federal graduation rate there has dropped from 27 to 13 percent in the last five years, while the GSR has risen from 35 to 64 percent. At Indiana University, the GSR for men's basketball players is 64 percent, but the federal rate is 8 percent. At the same time, IU's academic progress rate, another NCAA metric for student success, is among the highest in its conference and the players who did not transfer or get drafted all graduated, said IU spokesman Mark Land.

Men’s basketball programs, with their frequent transfers and the so-called “one-and-done” phenomenon, often have the larger discrepancies, but other sports are not immune. The GSR for Baylor University's football team is 72 percent, but the federal rate is 54. At the University of Alabama, the football team's GSR is 80 and the federal rate is 60. The University of Miami baseball team’s GSR is 100 percent while the federal rate is 22.

University officials said that several members of the team’s most recent graduating class were drafted, meaning they were not included in the federal rate despite being in good academic standing when they left. Jennifer Strawley, Miami’s deputy director of Athletics, said many of these students do come back one day to graduate, and thanks to Miami’s scholarship rules, they do so on the university’s dime. According to the NCAA, 12,979 athletes have returned to college to complete their degrees since 2004.

“At that point they’re already locked into that federal rate and counted against us,” Strawley said.

Critics continue to be skeptical of the GSR, however. Allen Sack, a professor of sports management at the University of New Haven, said the rate is valuable, but not as an indicator of a college’s success. The federal rate measures a college’s ability to retain and graduate students, he said, while the GSR is more about a student’s persistence to find a school or sports program that’s the right fit.

“I believe strongly, as a professor, that we need to retain our students, athletes and non-athletes,” he said. “These students are leaving in good academic standing, but what happens to them after that, exactly? These kids are leaving an institution instead of building up the social capital that comes from earning a degree, having friends that went to the same college as you, becoming an alumnus. In my point of view, that is a failure for those schools.”

But David Wyman, the associate athletic director of academic services at Miami, said that the discrepancy highlights why the GSR can provide a more accurate idea of athlete success at a college other than who simply graduated within six years.

“The federal rate really only shows one picture,” Wyman said. “We had four baseball players leave the most recent class because they were all drafted, but they all left eligible. It’s hard not to see that as a success.”

The release of this year's data comes about a week after a report revealed the extent to which some members of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill athletic department (and some professors) were willing to commit academic fraud to keep players eligible, calling into question the idea that eligibility is even a reliable metric of success. For 18 years, university employees there knowingly steered about 1,500 athletes toward no-show classes that never met, were not taught by any faculty members, and where the only work required was a single research paper that received a high grade no matter the content.

"This is a logical outgrowth of the use of eligibility and retention metrics," Richard Southall, director of the College Sports Research Institute at the University of South Carolina, said. "The focus on graduation rates and success rates just rewards this type of behavior."