You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

WASHINGTON -- The U.S. Department of Education today will release what is likely the Obama administration’s last chance to set regulations to clamp down on for-profit colleges. But this second iteration of “gainful employment” rules will fail to please either advocates for the for-profit sector or its critics.

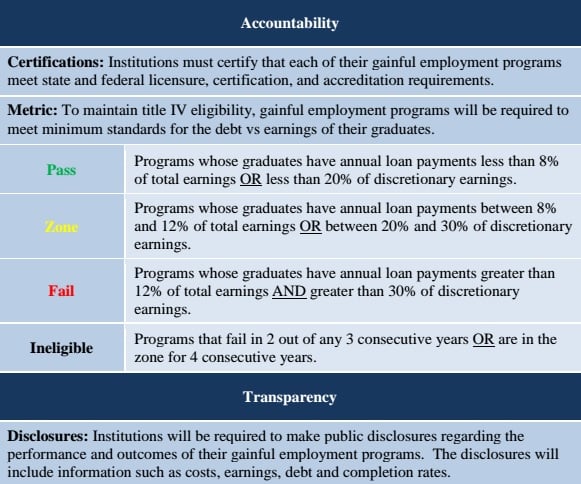

The final version of the regulations will not use a student loan default rate, which was one of two metrics for judging colleges in the draft the department released in March. The rules will feature unchanged standards for graduates’ debt-to-earnings ratios.

Audio Discussion of 'Gainful' Rules

Our "This Week" podcast will feature a conversation about the implications of the new gainful employment regulations. Bridgepoint Education's Vickie Schray and the New America Foundation's Ben Miller will join Doug Lederman for tomorrow's discussion. Click here to receive an email alert when "This Week" is published.

Department officials gave reporters some basic facts about the complex regulations on Wednesday (see chart). They said the rules, an "informal" version of which is available here on Thursday morning, are strong and would “capture the vast majority of poor-performing programs.” The final regulations will be published in the Federal Register on Friday, but a preview is available here.

Consumer advocates, however, were calling the rules weak even before they were released, at least officially.

“The final gainful employment regulation does not do enough to stop the fleecing of students and taxpayers,” the Institute for College Access and Success (TICAS) said in a written statement.

Gainful employment applies to vocational programs, including most of the for-profit sector’s offerings. Non-degree programs at community colleges would also need to comply with the rules, which are set to go into effect in July 2015. So would some non-degree programs at four-year nonprofit institutions, both public and private

Yet for-profits will feel almost all of the sting from gainful employment.

Arne Duncan, the education secretary, said Wednesday that an estimated 1,400 academic programs that enroll 840,000 students would fail to meet the standards with their current performance. Fully 99 percent of those programs are at for-profits, he said.

The draft rules from earlier this year would have snagged an estimated 1,900 programs, enrolling about 1 million students, with 98 percent being in the for-profit sector.

“Too many of these programs fail to provide students with the training they need,” said Duncan, while also “burying” students in debt.

The federal government contributes $22 billion each year to gainful employment programs, he said, including $16 billion in loans and $6 billion in Pell Grants.

“We believe American taxpayers deserve an honest return,” said Duncan.

Department officials said they dropped the loan-default standard to create more “streamlined” regulations. They said feedback from the public, which included 95,000 comments, led to the move.

For-profit advocates, however, are certain to argue that the change was mostly about protecting community colleges.

Trade groups for the two-year sector had argued that the programmatic default rates included numerous technical problems. They also cited an allegedly inherent flaw in holding programs accountable for the default levels of the relatively few students who borrow to attend community college.

“Proposed metrics, which are primarily and appropriately focused on programs that lead to excessive debt, indiscriminately impose expensive and burdensome reporting and disclosure requirements on all institutions with gainful employment programs, regardless of their cost, borrowing rates and risk to students,” the American Association of Community Colleges and the Association of Community College Trustees wrote in a May letter to the department.

The elimination of the loan-default metric follows the federal government’s release last month of the first installment of sanction-bearing data for tightened loan-default rates at the institutional level. The department made adjustments to the rates of community colleges that were close to failing, which rankled for-profits, who complained about preferential treatment. However, adjustments also were made to rates of for-profits and colleges from other sectors, including historically black colleges and universities.

On Wednesday the department said it still would track default rates for gainful employment programs. That information, as well as data on former students’ wages, completion rates and debt levels, would be available to both students and regulators, they said. But the data would not be used to formally penalize institutions.

Legal Challenge?

The administration’s first attempt to create gainful employment rules was also hotly debated. Released in 2010, those regulations included two debt-to-income standards and a loan-repayment rate, which required that at least 35 percent of a program’s graduates are actively repaying their loans.

A federal judge in 2012 ruled that the department had failed to adequately justify the setting of its loan-repayment rate. But the judge signed off on the general thrust of gainful employment.

The for-profit industry is likely to challenge this version in court as well, observers have said.

When asked if the elimination of loan-default rates was an attempt to better inoculate the regulations from a lawsuit, officials said they had carefully studied legal issues across the full breadth of the rules. One department official described this attempt at gainful employment as a “policy that will withstand legal scrutiny.”

A sticking point for the for-profit sector about the draft version from earlier this year is the stricter debt-to-earnings standard. To pass, a program’s graduates must have annual loan payments that are less than 8 percent of their wages or less than 20 percent of their discretionary earnings. That standard remained unchanged, according to a fact sheet the department distributed Wednesday.

The administration’s first set of gainful employment rules set that standard at 12 percent of wages. But this time around, programs that fall between 8 and 12 percent are in a warning “zone.” They would fail if they don’t get to at least 8 percent for four consecutive years. Programs that go above 12 percent for any two of three consecutive years also fail.

That tougher standard will make a big difference, department officials said Wednesday. Only 193 programs would have failed the previous version of gainful employment, compared to 1,400 this time around.

The Association of Private Sector Colleges and Universities (APSCU), which is the for-profit sector’s primary trade group, said Wednesday that the department has failed to give a rationale for including the lower threshold and zone. The group also said the regulations would take federal financial aid away from millions of students while stymieing national college completion goals.

Proponents of tight gainful employment rules weren’t happy either. They have long pushed for metrics that include students who fail to graduate but still rack up debt.

“In particular, the final regulation lets programs where most students borrow but few graduate keep using taxpayer dollars to bury students in debt they can’t repay, so long as they limit the debt of the few students who complete,” TICAS said in a written statement.

Consumer groups, however, had also said in the past that for-profits could game loan-default rates.

For example, TICAS said in its May comments to the department that “evidence is clear that some colleges are manipulating their cohort default rates by putting former students in forbearance during the window when default rates are being measured regardless of whether it is in the borrowers’ best interest to do so.”

TICAS and other groups called for the department to bring back a repayment rate to help fix this problem.

For-profits also questioned the validity of the loan-default rate. For example, a handout from APSCU's meeting this month with the feds called the rates arbitrary and inconsistent with the institutional default-rate standard.

'High-Performing Programs'

The final rules will be enormously complex -- the draft version was 841 pages long. So it’s likely that new wrinkles will emerge as experts pore over them today. However, department officials said the elimination of default rates was the one key change.

Some for-profit advocates had complained about the draft version’s requirement that vocational programs meet all state professional licensure requirements as well as hold programmatic accreditation. This is a particular concern for online graduate degrees, which enroll students in various states and where students might not seek employment in a program’s strictly defined area of accreditation.

Those requirements remained in the final version, department officials said, with only minor tweaks.

Duncan was less pugnacious in his comments about for-profits than he was during a call with reporters for the March release.

He praised some major for-profits for introducing scholarships and offering a free trial period to new students. The University of Phoenix and Kaplan Inc. both created trial periods a few years ago, which hurt their bottom lines.

Duncan predicted that gainful employment would encourage for-profits to improve their academic offerings, noting that they have time to make changes before the rules kick in. He said “greater accountability” will benefit both students and higher education.

“We would love to see high-performing programs expand,” said Duncan.

The department will continue to keep a close eye on for-profits. Today it announced plans to create an interagency task force to oversee the industry.

The task force will strengthen existing cooperation between various federal and state agencies, the department said. It will meet at least once a quarter to “coordinate their activities and promote information sharing to protect students from unfair, deceptive, and abusive policies and practices.”