You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

After a gunman opened fire at Florida State University’s Strozier Library and injured three students in November, many praised the library’s security system and the quick response of police officers, who shot and killed the assailant.

Also earning praise from administrators and campus security experts were the actions of the roughly 300 students who were studying inside the library at the time. Students quickly abandoned their belongings to escape out a back exit or seek cover. They hid behind bookshelves and barricaded themselves inside classrooms, waiting for an all-clear from the university as a gunfight erupted outside the building.

But students’ responses to campus emergencies are not always so exemplary, especially when the sound of gunfire isn't prompting them.

“I wouldn’t make a general statement that students are not at all prepared,” said Byron Piatt, emergency manager at the University of New Mexico. “But I would certainly feel a lot better if they took emergencies more seriously.”

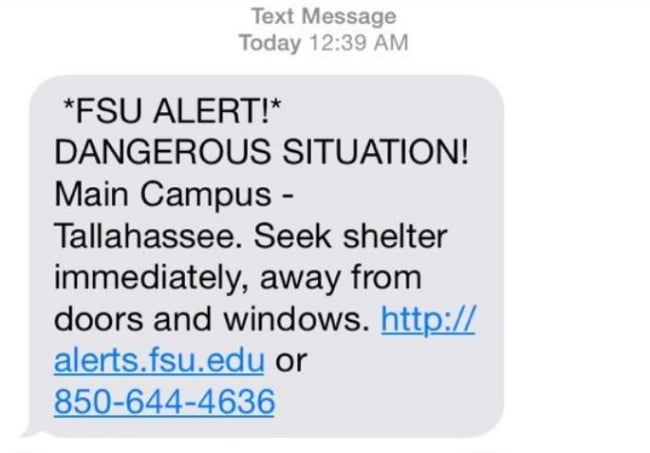

Last December, the University of New Mexico received a bomb threat directed at three buildings packed with students taking morning classes the week before final exams. The buildings in question neighbored 400 others, on a campus of 30,000 students, located in the middle of New Mexico’s most populous city. As officials raced to interrupt a Board of Regents meeting to alert the university's president, the campus police chief gave an order to Piatt and his team. A message was sent out to students and faculty through email, text message, and social media: “Please evacuate Mitchell, Ortega, and Popejoy Halls at this time.”

Most of the students and faculty fled the buildings, lining up in the cold outside, but two classrooms in one building didn’t empty, Piatt said.

“We heard that one class would look out the door and see what the other was doing,” he said. “In turn, the other class was looking out their door to see what they were doing. Neither of the classes evacuated because they didn’t see the other one leave.”

The bomb threat was ultimately found to be a hoax, but similar situations can arise during fire and tornado emergencies, as well. A group of students studying in a library may not leave the building when a fire alarm goes off unless they see other students move first. The tendency not to quickly react to emergency alerts is not just characteristic of students, Piatt said. It’s a habit many older adults also possess, though they may first develop it in college.

“When we’re in elementary school or high school, and we hear a fire or tornado siren, we’re trained what to do and there’s an adult making sure we react,” Piatt said. “Once, we’re in college, we no longer always have an adult presence who is that failsafe. And the adults who are present can be just as out of practice as the students, or they think well they’ve heard this siren before and nothing happened so there’s no need to be proactive this time.”

Part of the solution may be raising the bar on when colleges send out emergency alerts -- something many colleges say they already try to do, though one wouldn’t know it reading the tweets of aggrieved students awoken by emergency text message alerts. "Got a text alert from college," one student tweeted earlier this month. "Got excited. 'Be careful on roads because of freezing rain.' Fuck off. Only text if classes are canceled." Tweeted another, "the college text messaging system is possibly the most annoying thing on planet earth."

Students at the University of Central Florida once openly mocked its emergency alert system, according to Daphne Kopel, the co-author of a study exploring student perceptions of emergency alerts at the university. When a former student committed suicide in a campus dorm room last year and his body was found lying next to a backpack full of bombs, students began to take the alerts more seriously.

“UCF’s alert system was a popular topic of conversation prior to the planned attack due to the high volume of alerts students and faculty received,” said Kopel, who is also a graduate student in applied experimental human factors at the university. “This caused many people to dismiss them regardless of there being a potentially dangerous situation.”

The researchers surveyed 148 UCF students in the aftermath of the suicide and found that their perceptions had begun to change. After the incident, the students were 15 percent less likely to say they heard other students making fun of the system. More students said they were now satisfied with the alert system and that they take the alerts seriously.

It’s a pattern seen elsewhere, said William Taylor, the president-elect of the International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators. Emergency alerts have been required since the Clery Act was adopted in 1990, but even the federal government and many colleges didn’t take them as seriously as they do today until the 2007 mass shooting at Virginia Tech. One positive side effect of campus tragedies is that students, faculty, and emergency personnel do tend to learn from them, Taylor said.

The student response to the shooting at FSU last month, he said, is an example of that learning curve.

“The students knew what to do,” Taylor said. “We try to stress to faculty, staff and students this idea of ‘run, hide, fight.’ Obviously, the students did just that. They blocked doors. They got away if they were close to an exit. The students themselves had a lot to do with why there were no more injuries.”