You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Leaders of a national movement to ease the regulatory burden on colleges and universities that offer distance education say the effort has passed its tipping point after more than a third of the states have joined in less than a year.

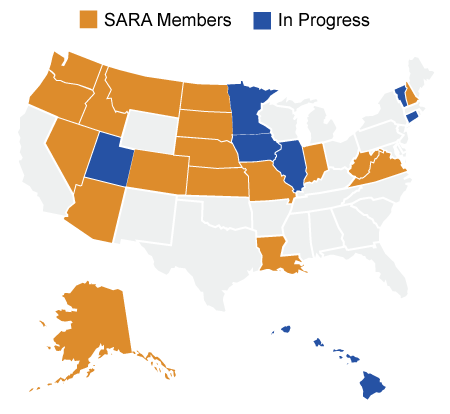

With Tuesday’s announcement that New Hampshire had joined, the National Council for State Authorization Reciprocity Agreements, or SARA, has 18 member states. Another seven states -- Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, Utah and Vermont -- have passed legislation that would enable them to apply or are in the process of doing so. In other words, the organization is close to hitting the milestone of recruiting half the states in the country.

Marshall A. Hill, executive director of SARA, said the interest has been “remarkably better” than anticipated. “We thought that if we got 10 states to join in the first year, we’d feel good about that,” he said. “Now we’ve got 18.”

SARA aims to simplify how college and universities become authorized to offer distance education to students in other states. Today, individual institutions have to apply to operate in every state from which they intend to enroll students -- a time-consuming and expensive process that involves navigating and keeping up with each state’s changing regulations.

Hill likened that system to having to get 50 different driver’s licenses to be able to drive in every state. SARA, similar to how driver’s licenses actually work, has to do with reciprocity. Once a state joins SARA, institutions there can apply for blanket approval to offer distance education to students in the other member states or continue to handle state authorization on their own. An agency within each state -- a board of regents, commission of postsecondary education, or university system office, for example -- approves those applications.

SARA has partnered with four regional education compacts -- the Midwestern Higher Education Compact, the New England Board of Higher Education, the Southern Regional Education Board and the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education -- to recruit states. Hill and the national council oversee the effort.

“I’m completely convinced that if we had gone a different route, we would not have had 18 states,” Hill said. “It’s a complexity of management that takes up a fair amount of time, but it’s the right way to be doing this.”

The number of member states could actually have been higher, but progress in some states was held back by scheduling conflicts. Texas’ legislature, for example, only meets every other year, so legislation paving the way for SARA membership has had to wait until next spring to be introduced. New Mexico’s legislature, meanwhile, only meets for 30 days in even-numbered years and ran out of time to consider a bill this winter, Hill said.

Not all states are convinced that SARA is the solution to state authorization, however. In some states, regulators have expressed concerns that they will be unable to protect students from predatory institutions if they join SARA. Other states have been unwilling to part with the revenue generated by state authorization applications. In Utah, for example, institutions pay between $1,500 and $2,500 a year.

“Frankly, I think the core of this is that SARA, reciprocity -- whatever you want to call it -- is really an institutional initiative that’s being driven by a desire to cut costs,” said David C. Dies, executive secretary of the Wisconsin Educational Approval Board. “It’s not necessarily about protecting students.”

SARA membership costs $2,000 a year for institutions with fewer than 2,500 full-time students, or less than what it costs to be authorized to operate in Alaska. Institutions with fewer than 10,000 and more than 10,000 full-time students pay $4,000 and $6,000 a year, respectively. In states such as Alabama, Mississippi, Utah and Wisconsin, where regulators have expressed skepticism, institutions are therefore pressuring regulators to join SARA.

“People hear from the institutions who are advocating for it,” Dies said. “They’re not hearing from the consumers who are potentially affected somewhere down the road. That voice is missing.”

There are, however, signs suggesting some of those states may join if SARA’s momentum continues. Minnesota, which is regarded as having some of the strictest regulations for distance education providers in the country, submitted its application Tuesday, Hill said. Even Dies said Wisconsin “may at some point as a state choose to become a SARA participant,” although he remained concerned that the state would lose access to student outcome data if institutions no longer had to go through the approval board to be authorized.

“I don’t think the controversy is going to go away, but I think this is a case of the higher education community figuring out a way to make lemonade out of a situation that initially appeared to be all lemons,” said Terry W. Hartle, a senior vice president at the American Council on Education who serves on SARA’s national council. “For many colleges and university officials, they would say it’s unfortunate that we had to come up with something like this, but given the challenges that we’re facing, the fact that something like this could be created ... is a terrific sign that this really met a need that exists.”

SARA was launched with funds from the Lumina Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, but is in the process of transitioning over to being a member-supported organization. Its budget for this fiscal year calls for SARA to collect $720,000 from member institutions, and the organization has so far collected about $300,000, Hill said -- and that money has only come from institutions in seven or eight states. The organization now has over 100 approved college and university members.

SARA also has the federal government’s blessing. Hill said he expects that the U.S. Department of Education will issue a new rule on state authorization in the spring (plans for a new rule were delayed this summer), and that the rule will contain language supporting reciprocity arrangements such as SARA.

“[Under Secretary of Education] Ted Mitchell has been very, very supportive in his public remarks about the work that we’ve been doing,” Hill said. “A few of my colleagues and I met with him this summer, and the first thing he said was, ‘We don’t want to mess up what you’re doing.’ ”