You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Undocumented college students have a much higher level of anxiety than the population at large, likely caused by a unique set of challenges they face as a result of their legal status.

Concerns related to finances, fear of deportation and a sense of isolation weigh heavily on undocumented students, according to a study released today from the Institute for Immigration, Globalization and Education at the University of California at Los Angeles.

In the survey of undocumented undergraduates, 28.5 percent of male and 36.7 percent of female participants reported a level of anxiety that was above the clinical cut-off for generalized anxiety disorder, which means a moderate or severe level of anxiety. That’s compared to 4 percent and 9 percent from a sample of the general population. or overall? -sj Also tweaked this based on what the authors told me. It's overall population of adults, not just college students.

Undocumented students have been marginalized and neglected and their potential is under-realized, the study's authors write.

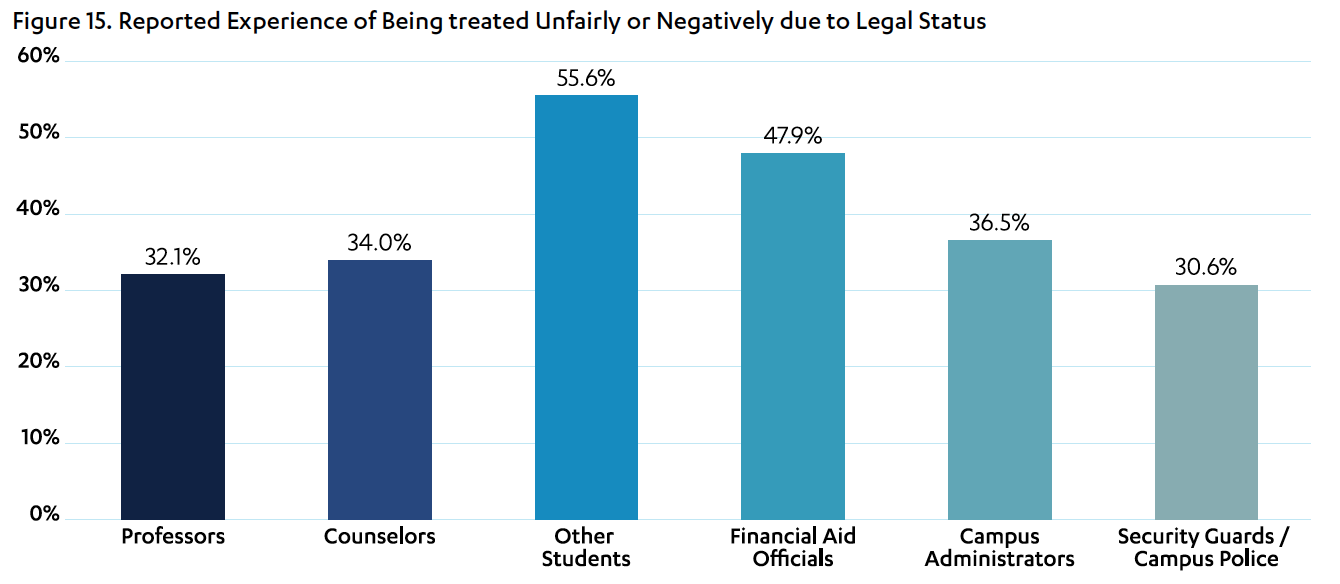

“There’s a very real chance that administrators in question have no idea what (undocumented students) go through,” one survey respondent said. “None at all.”

Study Participants at a Glance

88% arrived in the U.S. at age 12 or younger

87% have at least one undocumented parent

76% worry about being deported or detained

61% had annual household income below $30,000

48% attended four-year public college

86% of those students had a GPA over 3.0

42% attended two-year colleges

79% of those students had a GPA over 3.0

The Pew Research Center estimates that there are between 200,000 and 225,000 undocumented immigrants enrolled in college. But research on the population is limited largely to students at selective four-year colleges or within specific states, according to the study. Undocumented students, for obvious legal reasons, also are a difficult population to reach.

This study consisted of a largely anonymous survey of 909 participants from 34 states. They represented 55 different countries of birth, though the majority of respondents (657) were from Mexico. They attended mainly 4-year public colleges or 2-year colleges.

The geographic and institutional variety shows that colleges can’t assume they don’t have undocumented students, said Robert Teranishi, an education professor at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education and Information. Teranishi and his two co-directors of the immigration institute were the principal authors of the study. The other two authors were Carola Suárez-Orozco, an education professor, and Marcelo Suárez-Orozco, dean of the graduate education school.

The study focuses on the effects of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which was started by President Obama in 2012 to temporarily protect qualified youth from deportation. About 66 percent of the participants applied for and received deferred action. Of those, more than 85 percent said it had a positive effect on their studies.

Because they had legal reprieve, students who had attained DACA status found it easier to find quality housing, get internships relevant to their field of study, and in some states, get driver licenses that reduced their commute to campus.

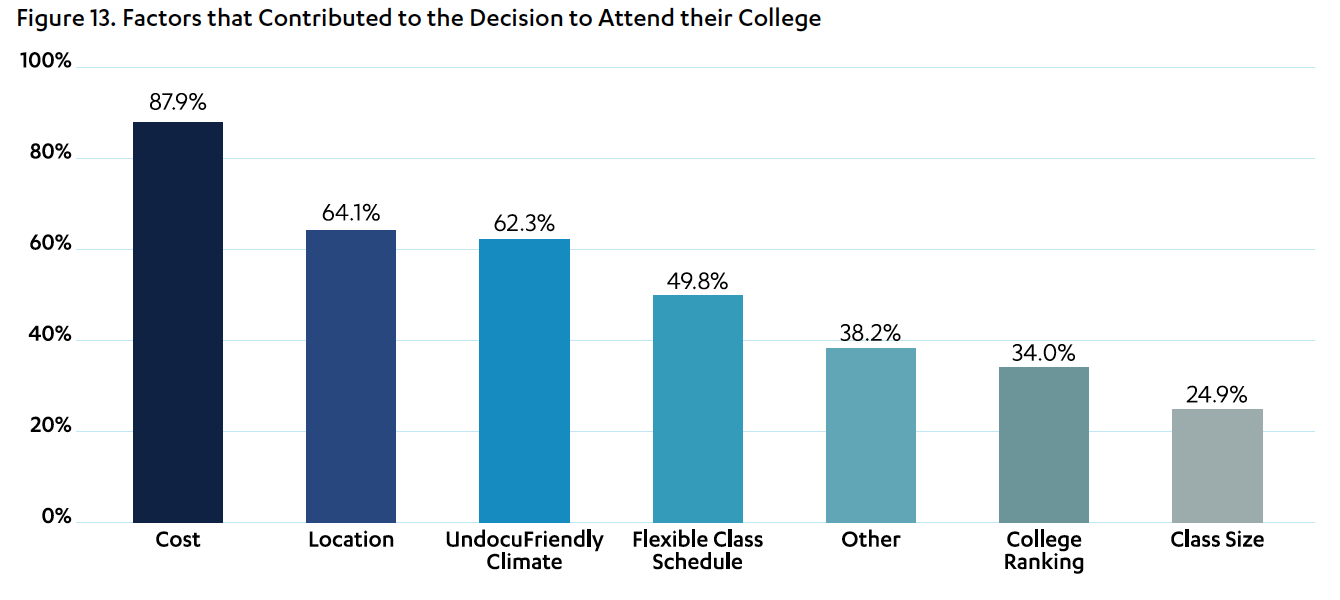

About 72 percent of DACA recipients were able to find paid work experience to help pay for college, compared to 28 percent of students without DACA. Nearly 77 percent of all survey participants reported moderate to extreme concerns about financing their education.

Regardless of their DACA status, undocumented students don’t qualify for federal grants and loans, and state- and institution-level policies are a confusing hodgepodge.

“Students have to ask a lot of questions,” Teranishi said. “They have to figure out who they can trust. They’re getting conflicting information from administrators on campus, who also don’t know what the policies are.”

Nineteen states explicitly grant in-state tuition or grant aid eligibility to undocumented immigrants, while nine states have policies that restrict access to enrollment or in-state tuition. The remaining 22 don’t have such laws in place.

But that’s only a limited explanation, as individual institutions also have their own policies. In Arizona, for example, three community college districts explicitly provide in-state tuition for students with DACA status, even though the state prohibits it.

Teranishi also points out that some of the states that don’t explicitly grant in-state tuition to undocumented immigrants have good neighbor policies where residents of other states, and even Canadian and Mexican citizens, can qualify for in-state tuition.

Many students with DACA reported a reduction in feelings of shame, since they could be open about their status. At the same time, though, DACA recipients reported feelings of guilt and had higher levels of anxiety than those without the deferred action status.

While concerns about their own deportation were lower, 90 percent of DACA recipients worried about the deportation or detention of friends and family, compared to about 70 percent of non-DACA recipients.

Uncertainty also served as a distraction and stressor, since even those with a temporary status don’t know what will happen when DACA ends.

“It is not just stressful but also depressing for any human not being able or motivated to think, dream and plan a future,” said one survey respondent, a female student from a four-year public college in New York.

The study recommends that states offer equitable tuition polices and that the federal government reexamine financial aid guidelines. Colleges should review policies around issues such as financial aid, admissions and internships, and offer training for faculty and staff. Colleges could also create support groups or centers specifically for undocumented students, so they have a place to go to share concerns and seek resources.

Teranishi hopes those in higher education can look at this information not as part of a politicized debate about immigration, but as information to help serve students. These students are being admitted, he said, so colleges should make it a priority to help them succeed.

“These are really talented students,” he said. “They’re highly resilient. They’re working hard and succeeding despite the odds.”